High Hill

FAYETTE COUNTY, TEXAS

From Fayette County, Her History and Her People by F. Lotto, 1902:

Before the arrival of the Southern Pacific into Schulenburg High Hill was quite an important place. At that time it consisted of six stores - some of them made of self-made brick - and three blacksmith and wheelwright shops. It was built in two different localities at a little distance apart. The upper part of the town had the name of Oldenburg, but now the name of High Hill stands for the whole place.

High Hill is situated about three miles north of Schulenburg on top of a hill and its buildings and the tall steeple of its fine Catholic Church building can be seen in clear weather from Schulenburg. it is built on the E. Anderson league. West Navidad and Forster's Creek are in its neighborhood.

High Hill is a postoffice and a voting precinct of the county. It has a fine Catholic Church which was built in 1870 and of which Rev. Father H. Gerlach is the priest.

Theo. Helmcamp is the proprietor of a first-class saloon and also of a fine hall where the people of High Hill gather for amusement and entertainment. John Wick is the postmaster and merchant of that place. There is also a gin and blacksmith shop at High Hill.

High Hill is an old place. The oldest settlers of that place were Eckert, Hermann Bauch, the Fahrenthold and Eschenberg families, F. G. Seydler, ___ Perkins, ___ Green, ___ Adamek, A. Bilamek, Franz Wick, Anton Bednarz, Joseph Hollas, Joseph Heinrich, sr., F. Kleinemann, Geo. Herder, Gerh. Siems, Pl. Stuelke, Gerh. Nordhansen, Chas. Hinkel, Edward Schubert, Capt. Chas. Wellhansen, Aug. Knechler, Ernst Goeth, H. F. Hillje, who built the first cotton gin and oil mill in the High Hill neighborhood.

The population is German and Bohemian. Most of the High Hill people belong to the Catholic Church.

Nearby Historical Markers

|

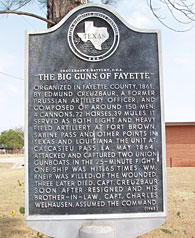

Creuzbaur's Battery, C.S.A.

"The Big Guns of Fayette"

FM 2672, 2.3 miles north of Schulenburg

Organized in Fayette County, 1861, by Edmund Creuzbaur, a former Prussian artillery officer, and composed of around 150 men, 4 cannon, 72 horses, 39 mules. It served as both light and heavy field artillery at Fort Brown, Sabine Pass and other points in Texas and Louisiana. The unit at Calcasieu Pass, La., May 1864, attacked and captured two Union gunboats. In the 75-minute fight, one ship was hit 65 times; Wm. Kneip was killed; of the wounded, three later died. Capt. Creuzbaur soon after resigned and his brother-in-law, Capt. Charles Welhausen, assumed the command. [1965]

|

| Other historical marker in the vicinity:

Old High Hill Cemetery

|

First Oil Mill in Texas

Missing from location at High Hill 4 miles NW of Schulenburg

Erected by Frederick Hillje, 1866, using German made sugar beet crusher adapted locally to seed processing. Later enlarged plant had regular milling machinery for cottonseed. After Galveston, Houston & San Antonio Railroad bypassed High Hill, Hillje move mill to Weimar, 1880. Marker Sponsored by: Mrs. E. M. Hubbard, Chas. Herder, Jr., Leroy Herder, Paul K. Herder, Henry Herder. [1967]

|

Celebrations at St. Mary’s Catholic Church, High Hill, Texas

A Footprints of Fayette article written by Carolyn Heinsohn and Dolores Guenther Vacek

In 1861, a small group of German-Moravian and German Catholics in the High Hill area, longing for church services, asked Rev. Victor Gury of Frelsburg to visit their community occasionally. Thus, the first Mass in the area was celebrated by Rev. Gury in the log cabin of Andreas Billimek, with subsequent services held at the home of Franz Wick.

Realizing the need for a proper place to worship, a permanent frame church, named Nativity of Mary, Blessed Virgin, was eventually built by 36 Catholic families in 1869. The name of the church is now more commonly known as St. Mary’s. The church was not blessed, however, until September 8, 1870. This church was eventually replaced by a second larger frame church in 1876.

As the number of families attending St. Mary’s increased, the parish felt a need to build an even larger church, so plans were begun in 1905 while Rev. Henry Gerlach was pastor of St. Mary’s. The enormous undertaking for a relatively small parish resulted in a magnificent Gothic Revival edifice of red brick, a dark slate roof, a 175-foot spire, and an exquisite interior. The parishioners, under the direction of contractor Frank Bohlmann, helped with the construction of the church, as well as donating the altars, statues and additional stained glass windows to supplement those that were saved from the previous church. This church, which still stands as a reminder of the faith and determination of its founders, was dedicated on September 8, 1906 – the parish now celebrates the two church dedications every year on the first Sunday of September.

However, it wasn’t until the summer of 1912 that the interior of the church was decoratively painted by two very talented artists, Ferdinand Stockert and Hermann Kern of San Antonio. St. Mary’s has now designated itself as the “Queen of the Painted Churches” in Fayette County as a result of the remarkable creative ability of these two artists. During the last year, almost all of the interior painting has been restored, retouched or repainted, with some of the decorative painting done in 1912 being uncovered and restored to its original splendor.

The parish will be celebrating its sesquicentennial anniversary of the blessing of the first church on Sunday, September 5, 2010 with Bishop David Fellhauer of the Victoria Diocese and the San Antonio Liedercranz Choir. However, anniversary celebrations are not a new event for this parish.

On Pentecost Monday, June 1, 1936, St. Mary’s parish held triple jubilee ceremonies, celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of the ordination of Msgr. Henry Gerlach, along with the twenty-fifth anniversary of his pastorate in High Hill, and the seventy-fifth anniversary of the first Holy Mass celebrated for the local Catholics.

The all-day celebration began with a colorful procession of school children, members of various parish organizations, other parishioners and many visitors from surrounding parishes, headed by a brass band, escorting the large number of prelates, clergy and nuns from the rectory to the church. Fifty little flower girls dressed in white preceded the jubilarian, followed by addresses in German and English being given by two little girls at the entrance to the church.

A special celebratory Mass was sung by the Men’s Choir, under the direction of Joseph Kainer, organist. Members of the choir were Joseph Stanzel, Rudolph, Ewald, Walter, Alphonse and Charles Heinrich, first tenors; Alfred Stanzel and Alphonse Schmidt, second tenors; Ludwig Heinrich, Leo Kainer, Franz Schmidt, Robert Heinrich and Robert Stanzel, first bass; Ferdinand Klesel, Ad Kainer, Rudolph Kahlich, Arthur, Leo and Beno Kainer, second bass.

After the religious celebration, the prelates and clergy were entertained in the school auditorium with a noon meal, including homemade chicken noodle soup made by Mrs. Sofia (Franz) Schmidt. Toasts were given to Msgr.Gerlach by two personal friends who were priests from Fredericksburg. A meal for the laity was served in the parish hall, where there were displays of Msgr. Gerlach’s clerical memorabilia and photos of all of the priests who had served the High Hill parish during its 75 years of existence. Three large beautiful cakes decorated for the three anniversaries, baked by Mrs. Mary Winkler and her daughter, Della, were served to the attendees. The afternoon was spent visiting and listening to congratulatory addresses.

After supper, a torch-light procession, headed by the band, went to the cemetery where prayers for the departed parishioners were recited. Returning to the front of the church, continuing services were held under a huge electric cross erected by Henry Ripper. The day’s activities were culminated with a four-act play in the parish hall. The characters were Rudolph Ripper, Rosa Kahlich, Reinhard Winkler, Rudi Boehm, Leo Kainer, Elvin Winkler, Ella Schmidt, Alphonse Heinrich, Beno Christ, Alphonse Schmidt, Alphonse Boehm, Henry Ripper and Victor Krischke. Music was furnished by the brass band and Heinrich’s Orchestra.

The annual commemorative parish celebration at St. Mary’s has evolved through the years, but the faith and dedication of its parishioners have remained strong, traits passed down from their ancestors whose lives revolved around their beautiful church.

Sources:

Southern Messenger; Vol. XLVII, No.18; San Antonio, Dallas and Houston, May 28, 1936.

The High Hill Centennial History 1860-1960; The Schulenburg Sticker, Schulenburg, TX, 1960.

The Origins of the German Moravians of High Hill, Texas

The history of the German Moravians who settled in the High Hill area of Fayette County is somewhat complicated, thus causing some confusion for their descendants, who may be attempting to research and document their origins. Their nationality is German, of course, but after acknowledging that fact, their history becomes somewhat convoluted.

Looking back at European history, their story begins in the 12th century with the systematic colonization of previously unsettled regions of the Czech lands and the conversion of extensive forests and moorlands into arable land with the pressure of necessity and the initiative of the sovereigns, the monasteries and convents, and the nobility, many of whom were of Germanic descent. This process of colonization received a powerful impetus in the 13th century, when streams of colonists flowed into Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia and the Hungarian Kingdom from Germanic regions. The German colonists, who came from overpopulated areas of their homeland, significantly took part in the settlement of thick, difficult-to-access forests along the borders of the Czech lands. They likewise brought along with them more refined agricultural techniques. The residences of inhabitants, at one time concentrated in the fertile lowlands, now covered all of Bohemia and Moravia, with the exception of the highest mountain ranges along the border, which were not colonized until the 16th to the 19th centuries.

Colonists from the German regions also relied on a more advanced legal system which precisely defined the relations between the serf farmers and the feudal lords. Most importantly, the German colonists, many of whom were artisans, craftsmen and merchants, also brought along with them the legal institution of “towns’, which subsequently became centers of crafts and trade. These towns rose up either in the settlements at prominent castles or were completely newly-founded. This resulted in the increase of a relatively close network of royal and tributary towns. The royal towns were larger and more important, receiving exclusive privileges from their sovereigns, such as the right to build fortifications, to develop a marketplace and the right to brew beer.

The German colonization also pervasively changed the national composition of the Czech lands. The originally integrated, Czech-speaking ethnicity ceased to be the exclusive population of the Bohemian-Moravian area. The German element’s share significantly increased, and the Kingdom of Bohemia and the Moravian Margraviate became a confederation of states inhabited by two nations. This cohabitation of Czechs and Germans existed for seven generations until 1946 after the end of WWII. This era of cohabitation encompassed a broad range from peaceful coexistence to a mutual rivalry and malice, which were undoubtedly potentiated by the rule of the Austrian Habsburg monarchy, which began with the death of a Bohemian King and the election in 1526 of Austrian Archduke Ferdinand I, a member of the Habsburg dynasty. By the time that the Thirty Years’ War ended in 1648, the Habsburg monarchy had already confiscated all of the remaining estates in Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia that were not already under their rule, thus beginning the control of the Czech lands by the Austrians. Also at this time, the institution of serfdom was strengthening, and concurrently the Habsburgs began the systematic process of re-Catholicization after the Protestant Hussite Reformation.

The Habsburgs were also instrumental in “Germanizing” everything in the Czech lands, from changing all of the Czech town names to Germanic names, to decreeing that German should be the official language for all of the subjects in their empire. Had it not been for the tenacity of Czech peasants in the remote areas of the Czech lands to preserve their native language, certain dialects would have been lost forever.

The rule of Maria Terezia between the years of 1740-1780 further strengthened Habsburg absolutism. In 1775 during her regime, the biggest riot of serfs in Bohemia and Moravia accelerated the issue of the “robota”, which required the serfs to work a minimum of three days per week for their feudal lords to repay their “debts”, thus leaving less time and provisions for their own needs. This created further bitterness among the serfs. Fortunately, the revolutionary movement throughout all of Europe in 1848 resulted in the abolition of serfdom and the lifting of the requirement of the “robota”. For the first time, people could leave or change jobs as they wished, attend school, decide upon their occupations, and marry whomever they pleased. This also made emigration possible.

In 1867, following a major loss in a war with Prussia, the Austrians made concessions with the Hungarians, resulting in the creation of the joint-centralized state of Austria-Hungary. Their power was now even more broad-based until the defeat of their empire in WWI.

The immigrants who arrived in the High Hill area in 1860 were descendants of the earlier German colonists, who had settled in northern Moravia centuries before their 19th century emigration to Texas. The names of these original families from Neudek, Moravia in the Empire of Austria (now Nejdek, Czech Republic) were Adamek, Bednarz, Besetzny, Billimek, Heinrich, Hollas, Schilhab and Wick. Interestingly, these families stayed with Czech families in Dubina, Texas, with whom they may have been acquainted in the Old Country, while traveling to their final destination at High Hill. Other German Moravian families from the area around Neudek arrived later. They were not Austrian by nationality, but Germans who lived in Moravia, which was then known as Mahren (the German name for Moravia) in the Empire of Austria, thus making them Austrian citizens, not by choice, but by decree. Their ancestral families were under Austrian rule for over 200 years prior to their emigration to Texas, but they still retained their German heritage and language with an overlay of Czech traditions.

Although the “Germanization” of the Czech lands was not offensive to the Germans living there, the newly-enforced laws, increased taxes and conscription into the Austrian Army after centuries of living among the Czechs were more than likely not acceptable. These factors, along with famine, poverty, lack of farming land, short growing seasons, primogeniture (the right of the eldest son to inherit his parents’ entire estate) and increased industrialization between 1848 to1860, thus eliminating cottage industries, were all instrumental in the emigration of thousands of people from the Czech lands to America in the 19th century. In addition, the Germans, who comprised approximately one-third of the population in the Czech lands, were becoming apprehensive about their position after the creation of Austria-Hungary, because Czech politicians were beginning their efforts to establish independence with their own statehood. World War I was the pivotal force that provided the impetus to fulfill their dreams of independence in 1918.

The Czechs were embittered about the “Germanization” of all that was familiar to them and more than likely associated their plight with the Germans who lived among them, creating an animosity toward anything “German”. These feelings were harbored for generations and were brought along with the Czechs when they emigrated to Texas. In spite of their feelings, however, the Czechs gravitated to German communities when they arrived in Texas, because many could speak or understand the German language and, therefore, did not feel so isolated. They could at least carry on business transactions with one another, but for the most part, the Germans and Czechs in Texas did not cross their barriers to marry one another until the 20th century.

The Austrian Empire was extensive, encompassing a large part of Central Europe, until the defeat of the country in WWI, when Bohemia, Moravia, a small portion of Silesia, Ruthenia and Slovakia, which had been under the rule of the Kingdom of Hungary for centuries, were all combined to create the new country of Czechoslovakia. Therefore, all immigrants from the Czech lands prior to WWI were citizens of the Austrian Empire, whether they were Bohemians, Moravians, German-Silesians, German-Bohemians or German-Moravians. To say that one’s ancestors immigrated from Czechoslovakia prior to its creation in 1918 is erroneous. The country only existed for 71 years from 1918 to 1989.

The Velvet Revolution in 1989 ended the 40-year Communist regime in Czechoslovakia, ultimately resulting in the final split of Bohemia, Moravia and Slovakia into the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic on January 1, 1993.

To clarify the persistent confusion about the German Moravians who settled in High Hill and other areas of Texas, a similar analogy could be associated to the early settlers of Texas in the pre-Republic era. They were Americans, who settled in Texas, but were officially citizens of Mexico, which was the ruling country of Texas at that time. Living under the Mexican rule did not make those settlers Mexicans by nationality, only temporary citizens of Mexico. Likewise, the German Moravians had no connection to the country of Austria that exists today; they were merely citizens of the Austrian Empire that had “swallowed up” their adopted homeland of Moravia. Their villages of origin are in northern Moravia, presently the Czech Republic, not in Austria.

Unfortunately, due to the Nazi atrocities in WWII, including the occupation of Prague and other Bohemian cities in the Sudetenland, the massacre at Lidice, and the lingering resentment of the “Germanization” of the Czech lands for centuries, the Czech government mandated that all remaining Germans in Czechoslovakia had to leave the country within a specified 24 hour period of time in January, 1946. If they wanted to stay, they had to become assimilated into the Czech population, speak Czech, and use the Czech spelling for their surnames, thereby severing all ties to their German heritage. The Germans, who decided to leave, had their property confiscated and were transferred in groups into East Germany, which was in a deplorable condition after the war. They first lived in isolation in enclaves located near chosen cities. Thus, it is difficult for the German Moravians and German Bohemians of Texas to find relatives in the Czech Republic today, unless their ancestors long ago changed the Germanic spelling of their names to Czech, which gave their descendants a reprieve from being exiled, or some of their German relatives chose to stay and assimilate the Czech culture. Also, many of the cemeteries with German Moravian burials were destroyed by the Communists during their regime in Czechoslovakia.

The names of all of the villages and towns were changed back to their original Czech names in 1946 after WWII. This only adds to the confusion when trying to research villages of origin, since the German names do not exist on contemporary maps. The following is an abbreviated list of some of the villages and towns in the region of northern Moravia where the German Moravians may have lived prior to their emigration to Texas. They are listed by their old German names followed by their present-day names in the Czech Republic:

| German

Altstadt

Bolten/Belt/Belthen

Bernardsdorf/Bernhartice

Deutsch Jasnek

Dittersdorf

Dorfel, Silesia

Freiburg

Friedeck/Friedek

Fulneca

Gross Petersdorf

Heinzendorf

Hotzensdorf

Kunvald/Kunwald

Laubeas

Neudek

Neudorfel

Neutitschein

Odrau

Petersdorf/Pettersdorf

Sednice

Schaltern/Slatten

Wagstadt

Weiskirchen

Zauchtl

|

Czech

Stara Ves

Belotin

Bernartice nad Odrou

Jasenik nad Odrou

Vetrkovice

Veska

Pribor

Frydek-Mistek

Fulnek

Dolni Vrazne

Hyncice

Hodslavice

Kunin

Lubojaty

Nejdek

Nova Ves

Novy Jicin

Odry

Vrazne

Sedlnice

Slatina

Bilovec

Hranice

Suchdol nad Odrou

|

Hopefully, this history of the origins of the German Moravians who emigrated to Texas will help to clarify some misconceptions that have resulted from a lack of knowledge about their journey from Germany to Moravia to Texas. A few German Moravian family history books include the history of the Czech people and the German colonists; however, their availability to the general public is limited. The history of the German Bohemians and German Silesians parallels the German Moravians with the exception of where their ancestors settled as colonists – Silesia or the borderlands of Bohemia.

Sources: Cornej, Petr: Fundamentals of Czech History; Prague, Czech Republic; 1992.

Polisenky, J.V.: History of Czechoslovakia in Outline; Prague, Czech Republic; 1991.

Simicek, Josef, MUDr.: The Hope Has Its Name – Texas; Lichnov, Czech Republic; 1996.