These histories were written by members of the Fayette County Historical Commission. They first appeared in the weekly column, "Footprints of Fayette," which is published in local newspapers.

Stephen Scallorn, M. D.

By Josephine White

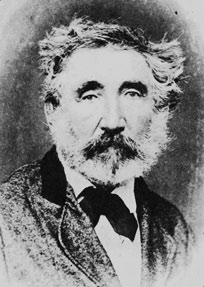

Stephen Scallorn was born on February 23, 1787 in St. Mary’s County, Maryland. He died on December 24, 1887 in Bastrop County at his son, Francis’, home near Upton, Texas. He was almost 101 years old.

In Stephen’s early childhood, his family moved to North Carolina, then to Kentucky where he met and married Mary “Polly” McClure on February 14, 1811. The Scallorns moved on to western Tennessee where he and Polly settled. Stephen began a successful practice of medicine for the next 25 years. During that time, he had become a prominent member and a deacon of the Big Muddy Primitive Baptist Church in Haywood, Tennessee. Polly died on March 10, 1833, shortly after the birth of her eleventh child.

On the 23rd of April, 1934, he married Martha Bullock with whom he fathered three more children. Stephen and Martha moved to Fayette County, Texas in 1838. In notes from Case #1171, Spring 1857 in Fayette County, Stephen Scallorn answered, “I came to Fayette County, Texas on the 8th of February 1838.” (He was 51 years old when he arrived in Texas, and apparently did not hang out his shingle to practice medicine again, but he did continue to treat family, friends and neighbors for many years.)

Stephen Scallorn and his family came to Texas along with his brother, William Scallorn, his family and other relatives, following in the footsteps of Stephen’s oldest son, John Wesley “Wes” Scallorn. Wes had come to Fayette County in 1834-35 with a number of his mother’s McClure relatives, including the Faires and Karnes families. He fought in the Battle of San Jacinto and died in 1842 in Dawson’s Massacre along with his younger brother, Elam.

The first Baptist church west of the Colorado River was organized in the home of Stephen’s brother, William Scallorn, in 1839. Stephen was the church’s clerk. The name of the church was Hopewell Baptist Church, later changed to Plum Grove Baptist Church. It was built on property located on Criswell Creek near the Criswell family cemetery, a short distance east of the community of West Point, Texas. Only the graveyard, known as the “Old Plum Grove Cemetery”, that surrounded the church now remains. The New Plum Grove Cemetery is located closer to Plum, Texas.

While worshipping at the Hopewell Baptist Church, Stephen Scallorn and his brother, William, had a disagreement over missionaries and did not speak for 44 years, not until their children got them together again on Stephen’s 100th birthday. They reconciled and talked all night. They died eight days apart - Stephen on Christmas Eve 1887, and William on New Year’s Day 1888.

Stephen Scallorn is credited with building and helping to organize a total of three Baptist churches: The Hopewell Baptist Church, later known as the Plum Grove Baptist Church, on Criswell Creek in Fayette County; a church built on land located on Mulberry, Creek in Fayette County, Texas (Fayette County Deed Records: Vol. M, p. 264), in which Stephen gave the deed for land for a school and church; and lastly, a Baptist church that Stephen, who at age 98, was credited with founding; it was located in Bastrop County, where he had moved in 1884 to live with his son, Francis Scallorn.

Stephen is buried in the cemetery near where the old Primitive Baptist Church once stood near Upton in Bastrop County. He is not buried in a Scallorn family cemetery as indicated on a nearby historic marker. The cemetery where he is buried is almost inaccessible as it is located in a brushy pasture on private property, down a lane not far from where Stephen’s historic marker is located.

Stephen’s marker reads in part: “Maryland native, Stephen Scallorn (1787-1887) lived in Kentucky and Tennessee, where he practiced medicine and was active in the Primitive Baptist Church before moving to Texas. He was attracted to the Republic by the favorable accounts of his oldest son John Wesley Scallorn, who served with the Texas army in the battle of San Jacinto. Stephen Scallorn and his brother, William, came to Texas with their families in 1837-38 and settled in the vicinity of Plum Creek in Fayette County....”

The marker further reads: “Two of Scallorn’s sons, John Wesley and Elam, died in defense of the Republic. Members of Capt. Nicolas Dawson’s outfit, they were attacked by Mexican forces near San Antonio in 1842 and died.”….

One of Stephen Scallorn’s descendants was Joe Alexander Cole, who was recently featured in a “Footprints of Fayette” article written by Joe’s grandson, Terry Cole.

Sources:

Morrell, Zenus N. Fruits and Flowers in the Wilderness, pp. 107-108, 152-153; Boston, 1872

Shook, J.W. Obituary of Stephen Scallorn

The Scallorns, Walter Freytag Papers, Fayette County Library & Archives

Wells, Richard A. Scallorn, Stephen & Stephen Scallorn – A Biography; The New Handbook of Texas, Vol. 5, pp. 907-908

Bernard Scherrer

by Connie F. Sneed

Bernard Scherrer was one of the first three settlers in the Biegel Settlement, the second oldest German settlement in Texas, which was located in Fayette County, Texas. He was born in St. Gallen, Switzerland, on August 20, 1807. He was educated there but left at the age of twenty-two and moved to America, arriving in New York.

He then went to St. Louis and down the Mississippi River to New Orleans. There he joined Detlef Dunt, a German traveler and writer, and sailed to Texas. Arriving in Brazoria, Scherrer received a passport from the Mexican alcalde, Henry Smith, on April 29, 1833. From Brazoria he traveled on foot to San Felipe, where he applied for a headright and rejoined Dunt. From there, they traveled to Mill Creek, later called Industry.

Mr. Scherrer stayed for a while with Johann Friedrich Ernst, and while there he taught Ernst how to roll cigars, since tobacco was a major crop. Ernst then began a cigar business. Scherrer received a headright Certificate Number 27 in Colorado County for one-third league of land. Joseph Biegel had received a land grant from the Mexican government and persuaded Scherrer to buy one-quarter of a league of land from him and settle in what was later called Biegel Settlement. Since neither Biegel nor his wife could read or write, Scherrer was an asset to them and the community. He owned a freighting business and was a successful farmer and a leading citizen. During the TexasRevolution Scherrer served as a soldier in the John York Company of Edward Burleson's Regiment. Also, he served in the volunteer unit of the "Dixie Greys" during the Civil War. It was organized on June 8, 1861. After the republic was formed, Scherrer was appointed justice of the peace of Precinct Number 3 in Fayette County by President Sam Houston. Also, he served as county commissioner in charge of roads and bridges from Biegel to Rutersville along the La Bahia Road. He was appointed commissioner in 1842 and 1847. On February 3, 1845, Bernard Scherrer and Gesine Eliza Margarete Koch were united in marriage at Industry by his good friend, Friedrich Ernst. They had seven children. Bernard Scherrer lived on his farm in the Biegel Settlement until his death on November 15, 1892. All that remained of the Scherrer estate in 1990 was a little log cabin in Henkel Square in Round Top. The cabin was his first home in Texas. It bears a historical marker erected in 1992 with the following text:

BERNARD SCHERRER

(1807 -1892) Bernard Scherrer left his native Switzerland at the age of 22 for extended travels before reaching Texas in 1833. After serving in Burleson's regiment during the Texas Revolution, he received a land grant in Colorado County but settled in Biegel settlement (Fayette County) about 1838. Here he served as justice of the peace, county commissioner, and in 1845 he married Gesine Eliza Margarete Koch. He left his civic, farming and freighting duties to serve in the Confederate Army during the Civil War. This cabin, Scherrer's first residence in Texas, was moved to this location in 1975.

The land he owned is now covered by the waters of the Fayette Power Plant.

Sources: An Early History of Fayette County; La Grange Journal: Google Books

The Charles Henry Schiege, Sr. Family of Round Top, Texas

by Cynthia A. Thornton

Charles Henry Schiege, Sr. was born Carl Johann Rudolph Schiege on June 1, 1815 in Neisse, Silesia, a province of Prussia. His parents were Carl and Johanna Wagner Schiege.

Charles traveled to Texas in 1847 and 1851, returning to Prussia each time. On July 4, 1855 aboard the ship Franchisca, Schiege and his bride, Carolina Schubert, arrived in Galveston. Carolina was born on August 6, 1820 in Neisse, Silesia.

Carl Johann Rudolph Schiege became a citizen of the United States in 1855 and changed his name to Charles Henry Schiege. Charles and Carolina settled in the Biegel Settlement in Fayette County, Texas.

Charles and Carolina had four children, with only one living to adulthood. Their children were: Charles Henry, Jr., born on September 15, 1858; Gustav, lived 7 days; Selma, a twin, born on July 17, 1861, and lived 14 months; Otto, a twin, born on July 17, 1861, and died in 1866.

In the 1860 United States census, Charles Henry Schiege, Sr. was listed as 45 years old, living with his wife, Carolina, and one son, Charles Henry, Jr. His vocation was cabinet maker, chair maker, locksmith and machinist. On September 2, 1861, Charles and Carolina purchased Lot 2 and 3, Block 29 in Round Top, Texas from G.C. August Bess for $100.00. Later Charles, Sr. purchased one acre from his neighbor, Conrad Schuddenmagen.

Charles H. Schiege, Sr. served in the Confederate Army with Captain Martin Martindale’s Company of Unattached Infantry, Fayette County under 22nd Brig. General William Webb, Commander at Fayetteville for six months. Charles is listed on the Confederate Army Veterans Pension Approval List #05275 from Fayette County, Texas, in Book 1 Comptroller’s Index Book.

Charles Henry Schiege, Sr. died on September 30, 1901 at 86 years of age. Carolina Schiege died on June 4, 1893 at 72 years of age. They are both buried in the Florida Chapel Cemetery outside of Round Top.

Their only surviving son, Charles Henry Schiege, Jr. was born in the Biegel Settlement near Fayetteville. By 1860, he was living with his parents on Block 29 adjoining the small village of Round Top. Charles, Jr. attended Pastor Johann Adam Neuthard’s School located on White Street in Round Top.

Charles, Jr. married Emma M. Frenzel on April 19, 1885. Emma was born on August 18, 1864 and died on January 26, 1892 without having children. She is buried in the Florida Chapel Cemetery outside of Round Top.

On November 30, 1893, Charles H. Schiege, Jr. married Marie Becker in Round Top. Her parents were Heinrich and Katherine Truede Becker. Marie was born on July 5, 1869 in Round Top. Charles and Marie’s 10 children born in Round Top were:

1. Henry Charles, born August 7, 1894 and died May 30, 1895. He is buried in the

Florida Chapel Cemetery.

2. Charles Adolph William, born June 30, 1896. He married Ida B. Treckmann on

December 25, 1920. Charles Adolph died February 9, 1953 and is buried in the

Florida Chapel Cemetery.

3. Katherine Justine, born on November 26, 1897. She married Oswald Gus

Tempel on June 23, 1920. Katherine died on February 21, 1987.

4. Lina Marie, born on March 10, 1899. She married Kinley Adam Ulrich on June

12, 1920. Lina died on May 15, 1988.

5. Frederich Charles, born on November 11, 1900. He married Migon Fricke on

January 21, 1923. Fred died on August 6, 1972 and is buried with his parents and

brothers in the Florida Chapel Cemetery.

6. Marie Emma, a twin, born on March 26, 1903. She married Rudolph Joseph

Legler, who was born on September 19, 1901. Marie died on January 20, 1983,

and Rudolph died on January 30, 1996. They are buried in the Florida Chapel

Cemetery.

7. Minnie Louise, a twin, born on March 26, 1903. She married William Luther

Clark on December 11, 1929. William was born on August 10, 1898 and died

on March 19, 1964. Minnie died on August 25, 1982 and is buried beside her

husband in the Florida Chapel Cemetery.

8. Annie Emma, born on November 5, 1905. She married Hugo Edward Ulrich on

September 12, 1928. Annie died on December 18, 1983.

9. Friedolin Gustav, born on March 25, 1908. He married Lily Lehman on February

26, 1931. Lily was born on August 16, 1912. Friedolin died on January 31, 1973.

They are both buried in the Florida Chapel Cemetery.

10. Frieda Marie, born on September 8, 1910. She married Edwin Herman Franke on

January 3, 1932.

All the Schiege children spoke High German before they learned English in school.

Charles Henry Schiege, Jr. was called Squire Schiege for his many years of service in

Round Top. Charles served as town marshal and alderman of the Round Top Town Council. He was mayor of Round Top from 1903 to 1908 and served as the Justice of the Peace, Precinct 3 in Fayette County. He was also a member of the Round Top Volunteer Fire Company for 30 years and was an active member of the Sons of Hermann Lodge No. 151.

The Schiege property on Block 29 in Round Top contained the family private house, a cigar factory, a cigar manager house, a carriage shed, a barn, stables and a large vegetable garden.

Charles H. Schiege, Jr. built a two-story grey and white frame house in 1885 before he married Emma Frenzel. The house faces Washington Street or Highway 237 in Round Top as part of the Round Top Inn. The house was built on a terrace and was surrounded by a picket fence. The house has three cellars, one lined with rock with cement flooring for a cooling effect to preserve milk, butter and eggs. The second cellar was for laundry and had a pipe that drained the washing water into a nearby gully. The third cellar was an area for potatoes, onions and other vegetables. The house also had a cistern that caught rainwater from the roof. The interior of the house was painted blue. There are large front porches on both levels of the front of the house with the ceilings painted blue. It is said that Charles would sit for hours in the late afternoon listening to classical music, playing his Edison record player that he obtained by mail from New York.

Charles H. Schiege, Jr. built a two-story grey and white frame house in 1885 before he married Emma Frenzel. The house faces Washington Street or Highway 237 in Round Top as part of the Round Top Inn. The house was built on a terrace and was surrounded by a picket fence. The house has three cellars, one lined with rock with cement flooring for a cooling effect to preserve milk, butter and eggs. The second cellar was for laundry and had a pipe that drained the washing water into a nearby gully. The third cellar was an area for potatoes, onions and other vegetables. The house also had a cistern that caught rainwater from the roof. The interior of the house was painted blue. There are large front porches on both levels of the front of the house with the ceilings painted blue. It is said that Charles would sit for hours in the late afternoon listening to classical music, playing his Edison record player that he obtained by mail from New York.

The cigar manager house was located near the back of the Schiege property. This house was for a single or a married man and his family, who managed the cigar factory for Charles H. Schiege, Jr. The manager house was a cottage of German vernacular design built in 1885 of native lumber. The house has 386 square feet downstairs with a small porch. The finished attic is around 195 square feet. This manager house was called the Schiege Dependency House, because it depended upon the use of other buildings.

The cigar manager house was located near the back of the Schiege property. This house was for a single or a married man and his family, who managed the cigar factory for Charles H. Schiege, Jr. The manager house was a cottage of German vernacular design built in 1885 of native lumber. The house has 386 square feet downstairs with a small porch. The finished attic is around 195 square feet. This manager house was called the Schiege Dependency House, because it depended upon the use of other buildings.

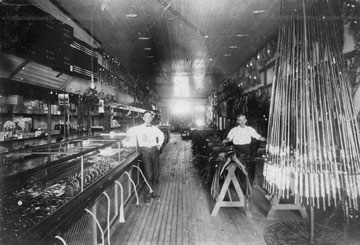

The cigar factory building built in 1885 of native lumber was a one-room frame building with a porch facing inside the property. The street side had stone steps from the front door down to the street below. Inside the building, a curved counter separated a working area and tobacco bins from an office. Several work stations were attached to one wall. The attic was finished. Beds lined the area for single men, who worked in the factory, to sleep at night. There was a ladder outside the building that allowed the men to enter the upstairs sleeping quarters. The cigar workers would have their meals with the family in the main house.

Charles Schiege began making cigars in 1881 in Round Top. His sign over the front doors of the factory building was “Segars & Tobacco”. This spelling of “Segars” was common in the 19th century and appears in early laws of the Republic of Texas. He used locally grown tobacco whenever possible and obtained shipments of tobacco from dealers in Missouri and Ohio.

Charles Schiege began making cigars in 1881 in Round Top. His sign over the front doors of the factory building was “Segars & Tobacco”. This spelling of “Segars” was common in the 19th century and appears in early laws of the Republic of Texas. He used locally grown tobacco whenever possible and obtained shipments of tobacco from dealers in Missouri and Ohio.

Schiege cigars were made to sell between 6 to 7 cents. The cigars were made by hand. At the height of his business, Schiege had men working at seven work stations that were attached to the walls for each man seated at the table. A low partition about 4” to 6” high separated each worker’s space from the other. The workman’s tools consisted of a square piece of hardwood board that was incised with gauges indicating different cigar lengths, a knife and a pot of gum tragacanth or similar substance. Each table had an attached sack of burlap into which the cuttings were deposited. Some of the labels on Schiege’s cigar boxes were: Texas Star, Great Sport, J.J. Vacek’s Favorite, Concha Regalia, La Rosa Supurba, and in 1932, the 50th anniversary box, The Boss, contained his photograph.

Schiege was a cigar producer for 48 years and was one of 56 cigar makers in Texas in 1885. In 1920, the United States had 9,778 cigar manufacturers. In 1920, Texas had 158 manufacturers, and one of the them was Shiege’s factory in Round Top. He was registered with the Internal Revenue Service as Factory #80, Third District. Schiege closed his cigar factory in 1932. He was 74 years old. In the late 1920s, cigar manufacturing became automated and was impacted by the Great Depression in the 1930s. Charles H. Schiege, Jr. Cigar factory in Round Top stands today as the only original building of a once widespread industry in Texas.

The vegetable garden was located to the north side of the cigar factory building next to the property line separating Schiege’s property from the Pochmann property. The stables, carriage shed and barn were located between the cigar factory and the manager house on the property.

Charles Henry Schiege, Jr. died during the evening on Sunday, March 17, 1935 in his house on Washington Street in Round Top. His wife, Mary, died on June 26, 1951. They are both buried in the Florida Chapel Cemetery, which is to the south just outside of Round Top, Texas.

The property has had many owners since the Schiege family occupied it. Historians owe a great deal of gratitude to one of the owners, Ted and Sandy Reed, for purchasing Texas Historical markers for the Schiege buildings. Without those markers, who knows how or where the old historical buildings might exist.

Sources:

Fayette County Deed Records, La Grange, Texas: Fayette County Clerk Office, Vol. R., p. 262

“The Cigar Industry in the Nineteenth Century”, Century Issue, US Tobacco Journal, 1900: 40

1880 United States Census, Charles Henry Schiege, Jr.

Texas Historical Commission, Austin, Texas: Charles H. Schiege Property

Fayette County Texas Heritage, Vol. II, pp. 414-415.

Wandke-Pochmann Collection, Stephen F. Austin State University, Nacogdoches, Texas

Information from Lawrence R. Nutt, San Antonio, Texas

Interview with Sandra Ree, 2012

Early Schools in Fayette County

by Gesine Tschiedel Koether

My mother, Isabella (Henniger) Tschiedel, used to tell me about how she walked to the Willow Springs School each school day in the 1920s. I found the Willow Springs Public School sign on Hwy 159 about seven miles outside of Fayetteville. My mom’s home was on Hwy 159 at Cummins Creek, so my odometer indicated that my mom walked around five miles round trip to school each day. My curiosity was piqued to learn more about the early Fayette County schools, but I also wanted to know more about the beginning of Texas schools.

With Texas becoming a state in 1845, public education was one of the primary goals of the early settlers. It took until 1854 for the Texas Legislature to pass the Common School Law which provided state support for schools. My search also found that a full twenty years earlier in 1834, John Breeding founded the first school in Fayette County in a log house on his land located between Fayetteville and Willow Springs. The first teacher at his school was a Mr. Rutland. The Texas Historical Marker on Hwy 159, near Darden Loop, details information on both the Breeding Cemetery and Breeding School, but the dates of the school’s operation are not listed. The Willow Springs Public School sign shows that it operated between 1871 to 1945. I continued my search for other information on early Fayette County schools.

With Texas becoming a state in 1845, public education was one of the primary goals of the early settlers. It took until 1854 for the Texas Legislature to pass the Common School Law which provided state support for schools. My search also found that a full twenty years earlier in 1834, John Breeding founded the first school in Fayette County in a log house on his land located between Fayetteville and Willow Springs. The first teacher at his school was a Mr. Rutland. The Texas Historical Marker on Hwy 159, near Darden Loop, details information on both the Breeding Cemetery and Breeding School, but the dates of the school’s operation are not listed. The Willow Springs Public School sign shows that it operated between 1871 to 1945. I continued my search for other information on early Fayette County schools.

There it was - a photo and short article on the Fayette County Schools Project in the Fayette County Record dated July 16, 1996. It stated that Fayette County Judge Ed Janecka had recently placed the first school sign at the site of the Oldenburg Public School. Those present at the placement were Leola Tiedt, former school teacher at Oldenburg; Fritz Lobpries, former County School Superintendent in Fayette County; Debbie Wied and Carrie Koenig, project researchers. The sign shows that the Oldenburg school had operated from 1890 to 1944.

There are over two hundred schools listed in historical files in the Fayette County Heritage Archives. The list includes schools from 1834 forward, including rural community schools for both white and African American students, as well as parochial schools.

Funding for Texas schools was made possible by setting aside two million dollars out of the ten million that Texas had received in the Compromise of 1850 for relinquishing its claim to land north and west of its present boundaries. The 1854 Texas Legislature based funding on an annual census. The first school census in 1854 showed approximately 65,000 students, and the state fund apportionment was 62 cents per student. The state found additional funding for supporting the schools and their teachers in the form of local taxation.

Fayette County is made up of approximately 614,000 acres, so with a poor road system in the 19th century, it is understandable that these early schools were founded in or near small communities. The students and teachers walked to and from school. As roads and transportation improved and laws changed, the small rural schools began to combine for both financial and staffing reasons. Today in 2017, there are five Independent School Districts in Fayette County located in La Grange, Schulenburg, Flatonia. Round Top-Carmine, and Fayetteville.

Texas public schools have come a long way since those early days of Texas statehood. Progress is great, but those small rural community schools served a vital role in educating our ancestors. There must be hundreds of stories from both teachers and students about early school days. I wish my mom was still here to tell me more about her early school days, but unfortunately, she isn’t. I will continue my search at the Fayette Heritage Museum and Archives and hopefully will gather enough information to write more stories about the schools in Fayette County.

Photo caption: Historical marker for the Breeding Cemetery and School

Sources:

“Fayette County School Project”, Fayette County Record, p. 1; July 16, 1996

Rox Ann Johnson, Fayette Heritage Museum and Archives

Texas Almanac – “A Brief History of Public Education”

School Days in Earlier Times

by Carolyn Heinsohn

School days in Fayette County in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were far different than those of today. There were many small one-room schools scattered around the countryside, usually within less than 10 miles of one another, so that the farm childen would have an accessible school to attend.

If two teachers were needed due to the enrollment, the one room was divided, sometimes with a curtain or sometimes with nothing at all. The teachers placed their desks at either end of the room, and each class faced their respective teacher. Children were expected to be quiet, so generally it was a feasible undertaking. Plus, a teacher had the authority to punish a child when he or she misbehaved. The disobedient child either got a good spanking with a paddle, had to sit in a corner on a dunce stool, or had to stay in the classroom during recess or the lunch break and study or write sentences several hundred times, such as “I will not talk in class.”

Children had to walk to school, some as far as four or five miles, rain or shine, hot or cold. Some had roads to follow, but others had to walk along cow paths, through multiple gates, creeks and pastures, often having to go through tall weeds that were wet with dew. If it had been raining, they also had to trek through mud, so by the time they got to school, they were wet, muddy and often very cold, especially in the winter. The school room was heated with a wood heater, so the first children to arrive in the cold mornings built the fire in the heater, which they then huddled around until they warmed up from their morning walk. At the end of the school day, approximately four children were expected to stay to sweep and clean up the school room.

In the early days, there were no grades. Instead, once a student knew one subject well, he or she would get the next book. A student could be advanced in arithmetic and still be in the first reader. There were four readers to complete; then came more advanced subjects like geography and Texas history. In addition, writing and spelling were also required. Penmanship was an art form that most students had to master. Children first used slates for writing and mathematic computations. Then tablets were added, but pages were not wasted, because only two tablets were provided during a school year, which was shorter than those of today. School materials were paid for with funds acquired in some type of fundraising activity, like box suppers or school plays.

The length of the school terms were based on the various seasonal farm chores. For example, school did not begin until after cotton picking was over. Initially, school attendance was not compulsory, so children might miss weeks of school, and many only completed three or four years of education. The need for their assistance on the farm surpassed the need for an education. School was definitely not always considered a necessity for girls. It was a general consensus that girls just needed to know how to cook, keep house, sew and work in the fields.

There were no hot meals served at school, so each child carried a lunch bucket to school. Usually, the lunch consisted of homemade white bread smeared with lard, or cornbread and butter, and maybe some jelly, molasses or honey. Occasionally, a special treat would be a baked sweet potato, a small piece of dried sausage, or a piece of cake. After Christmas, an apple or orange might be included. Students would sit outside under the trees to eat their lunches if the weather was nice. Of course, they had to contend with the flies and ants that also wanted to share their lunch.

Recess was a time of free unstructured play, generally without adult supervision. Various ball and tag games were popular, as well marbles, jump rope, hopscotch, mumbly peg and games like Red Rover, Flying Dutchman and Andy Over. In the earlier days, playground equipment was non-existent. Later, seesaws, merry-go-rounds and swings, built by the men in the community, were added to the school yards.

Sometimes there was not even an outhouse available for the students. The boys would head to the woods on one side of the school, and the girls to the other. Having a decent outhouse was considered a nice addition to a schoolhouse.

There were school trustees who hired teachers, determined their salaries and collected whatever fees were deemed necessary from the parents to help pay the teachers. The parents more than likely had little “say-so”, insofar as the disciplinary actions, rules and curriculum set forth by the trustees. There were no parent-teacher conferences or organizations and probably very little communication between the teacher and parents, other than a report card. Children were sent to school with the expectation that they would behave themselves, respect their teachers and get a basic “no frills” education. It truly was the era of “School days, school days, good ‘ole’ Golden Rule days.”

Two Brothers Thrown and Killed by Same Horse

by Gesine (Tschiedel) Koether

What are the odds that two brothers could be thrown and killed by the same horse?

Researching my Schmidt ancestors for a family book, The Portal to Texas History online offered up The La Grange Journal article of February 14, 1884 about the death of the two Schmidt Brothers. Were these my Schmidt ancestors?

Here is the article in its entirety: “The Journal learns from Mr. M. Zwernemann, who was in town yesterday, that a distressing accident occurred last Sunday in the Haw Creek neighborhood. Mr. Henry Schmidt was thrown by his horse against a tree and his neck broken, causing, of course, instant death. He leaves a widow and five small children to mourn his untimely death. Mr. Zwernemann also informed us that a brother of Mr. Schmidt was killed a few years ago while riding the same horse. It seems he [Wilhelm Schmidt] was running cattle and the horse fell, throwing him, and breaking his neck also.”

Yes, these were my family and to fully understand the magnitude of this article I needed more information.

Henry and Wilhelm were the sons of Fred and Mary Elise (Wunderlich) Schmidt of Prussia. Fred and Elise had married and decided to immigrate to the United States in 1852. Landing in Galveston the couple made their way to Shelby on foot and with their possessions on a wagon pulled by stock horses. In Shelby they joined relatives who had preceded them. Ultimately, Fred and Elise owned approximately 160 acres and had fourteen children of which eleven lived to adulthood. However, Fred, the family’s dad, died in January of 1880.

The 1880 census, taken in July 1880, showed only six of the widow Mary Elise’s children, were still home with her. Katy, the oldest, was listed on this census as blind. Wilhelm was 24 and the second oldest of the sons and still at home. All of the other sons (August, Rudolph and Frederic) were listed as farmers like Wilhelm. Only the youngest daughter, Alvena, was still attending school. Another loss came in April of 1881, with the death of Wilhelm, from the horse accident detailed above.

Henry Schmidt and his wife, Frances, had married December of 1871 and per the tax rolls, had 59 acres and two horses in 1881. The July 1880 census records of both Henry and the rest of his Schmidt family were only a page apart and appear to have lived close by. Henry’s horses were valued at $25 each on the tax rolls. It was in late February of 1884 when Henry was thrown from this horse and died, only three years after the death of his brother.

Henry Schmidt and his wife, Frances, had married December of 1871 and per the tax rolls, had 59 acres and two horses in 1881. The July 1880 census records of both Henry and the rest of his Schmidt family were only a page apart and appear to have lived close by. Henry’s horses were valued at $25 each on the tax rolls. It was in late February of 1884 when Henry was thrown from this horse and died, only three years after the death of his brother.

The Schmidt family needed horses to work the improved agricultural acreage and handle the livestock. There were plenty of opportunities for hard work to keep this family fed, clothed, healthy and educated. These horses would also have been useful for both transportation, farm work, hunting and delivery of products to another destination.

Just like humans, horses of all breeds have differing qualities and faults. Perhaps these two accidents were of no consequence of what the horse did or did not do but the situation caused these accidents. It would be interesting to know what became of this horse. As well as, it is interesting to note that Henry’s wife, Frances, was apparently pregnant with their sixth child. My research shows Frances never remarries but maintains the land with the help of her children, one servant and family. Researching our ancestors sometime provide us with unbelievable and sad stories to pass onto their descendants. These documents also show us nuggets of strong family ties. Rudolph Schmidt, my great grandfather, took care of his sister Katy, until her death in 1912. I strongly encourage you to check The Portal to Texas History site for interesting stories about your ancestors.

Picture of Heinrich Schmidt grave in the Haw Creek Cemetery, courtesy of Fayette Library and Archives

Sources:

www.Ancestry.com

The La Grange Journal, (La Grange, Tex). Vol 5 No 7, Ed 1 Thursday, February 14, 1884

Emil Schuhmann—A Renaissance Man

by Carolyn Heinsohn

One wonders how the gene pools get blended through time to occasionally produce a person with an abundance of creative traits? Some people are extraordinarily artistic; others have an engineering or mechanical mind, while others have innate musicality.

Emil Schuhmann, born in 1856 in Waldeck, Texas, the son of Carl and Christiane Voigterl Schuhmann, was one of those fortunate people who excelled in all three areas. He was a true Renaissance Man – a man who did many things very well. A talented musician, he was the guiding force for the well-known Schuhmann Band, popular in the late 1800s, that included his father, cousins and uncles, all members of several Schuhmann families who were early German settlers in the Waldeck and Walhalla communities. Their musical ability merited an invitation to the dedication of the State Capitol in 1893, which was quite an honor. Schuhmann, who outlived all of the other band members, composed his own music and shared his musical expertise with others by teaching organ, accordion and concertina.

Schuhmann also had a talent for folk-art stenciling, so was occasionally asked to beautify area homes with his artistic designs. He was very good at working with his hands in general and used his artistic ability, as well as his engineering skills, to complete a German-style Christmas pyramid in 1880, carving all of the figures and painting the settings himself.

Schuhmann’s family emigrated from Oberscheibe, a village in the Erzgebirge Mountains in Saxony, Germany, known for its iron mining. However, mining provided unreliable employment, so the miners supplemented their income by carving wooden toys, including the intricate Pyramide.

His family’s origin and heritage more than likely influenced Schuhmann to build his pyramid. Traditionally, it is a multi-story wooden carousel with a series of disks that are attached to a central axle. Decorated with carved figures, the disks rotate as the heat from candles turn a propeller on top of the axle.

His family’s origin and heritage more than likely influenced Schuhmann to build his pyramid. Traditionally, it is a multi-story wooden carousel with a series of disks that are attached to a central axle. Decorated with carved figures, the disks rotate as the heat from candles turn a propeller on top of the axle.

For his more elaborate pyramid, Schuhmann carved a domed building surmounted by a cupola, similar to a town hall. The two-story building is secured on top of a papier-mache mountain with “mine” tunnel openings; the mountain is made of lacquered German-language newspapers published in Galveston in 1872. A large propeller made of painted pasteboard blades sits on top of the dome; it turns by rising hot air from thirteen metal oil lamps attached to the pyramid at its three levels. The lower platform that rotates through the mountain features miniature miners with carts of ore and axes. Soldiers in 19th century uniforms march through the building’s first floor. Uniformed musicians occupy the second-floor platform. A “fenced-in front yard” is filled with carved animals and palm and pine trees that have branches made of painted wood shavings. A soldier guards the gate; a hunter aims his gun at a deer; and a shepherd herds a flock of sheep.

Schuhmann, who called his pyramid a “Baromet”, displayed it every Christmas for his nieces, nephews and other children in Waldeck, while playing Christmas carols on his concertina. Although the initial purpose of his pyramid was to entertain, Schuhmann’s handmade creation is a charming, beautiful piece of folk art that exhibits his high level of craftsmanship, ingenuity and imaginative self-expression.

Since Schuhmann never married and had no children, his nephew, Robert Wenzel, inherited the pyramid. After Wenzel’s death in 1969, his widow sold it to Miss Ima Hogg, the daughter of the famous Texas governor, James Hogg. Ms. Hogg, a well-known Houston philanthropist and preservationist, began acquiring various historical buildings in 1963, had them moved to a complex around the Old Stagecoach Inn at Winedale and then had them restored. She donated the buildings and property to the University of Texas in Austin in 1967. Schuhmann’s pyramid, which is part of Ms. Hogg’s Texas Folk Art Collection, can be seen in the McGregor-Grimm House in what is now known as the Winedale Historical Complex, a division of UT Austin’s Briscoe Center.

Schuhmann disliked farming - his primary interest was his music. Since he could not rely on his music lessons and band gigs to provide a steady income, he needed supplemental income from his farm. So, he entrusted his farming to a faithful Negro couple, Lufkin and Arizona Shelby. When Schuhmann died in 1937, he left 50 acres of his farm to the couple. His one and a half story German style home with cedar floors and stenciled walls unfortunately fell into ruins after his death.

Another Schuhmann family home was moved from Walhalla to Henkel Square in Round Top and is now part of the Henkel Square Market. It originally was assumed that Rudolph Melchior, a skilled artist who stenciled the walls and ceilings in a number of buildings in the area around Round Top and Winedale in the mid-19th century, had done the stenciling in that Schuhmann home. However, one source states that the stenciling was done by a family member, so that indicates that it more than likely was done by Emil Schuhmann.

Fortunately, professional conservationists with the Briscoe Center have helped preserve Schuhmann’s most outstanding artistic creation – his Christmas pyramid.

Photo caption: Emil Schuhmann's pyramid restored by professional conservationists, courtesy of Sidney Schuhmann Levesque

Sources:

Erwin, Ed. “The Texas of 1880s on Display at U.T.”; The Houston Chronicle, March 2, 2003

Taylor, Lonn. “The Great Pyramide”; Texas Monthly, December 2015

Photograph of Schuhmann’s pyramid; permission to reproduce from the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, the University of Texas at Austin; Benjamin P. Wright, Assistant Director for Communications

Schuhmann, Sidney S. “Emil Schuhmann – Early Waldeck Resident”; Fayette County, Texas Heritage, Vol. II; Curtis Media, 1996

Winedale, Texas. Fayette County, Texas Heritage, Vol. 1; Curtis Media, 1996

Sears Catalog Homes

By Barbara Arambula

Between 1908 -1940, Sears, Roebuck, and Co. sold approximately 100,000 homes in 447 styles by mail order catalog. After choosing and ordering a home plan from the catalog, within as little as two weeks the customer could expect to receive the 30,000 or so pieces of the new home in two boxcars at the nearest train station. These homes were sold in kits and included everything from pre-cut lumber, paint, nails, and shingles - everything except the labor to assemble the home. Each kit came with a leather-bound 75 page instruction manual embossed with the new home owner’s name. The 1908 Sears catalog gave a price range from $495 - $4115. Sears also offered the materials and plans for a schoolhouse.

I was recently told that a Sears home had been built in Fayetteville around 1926. One of the descendants of the original owner stated that the home was brought in on the railroad - which in Fayetteville was across the street from the building site. Being one of the largest plans available – the home took two years for construction to be completed. Are there others in Fayette County? When you think about the difficulty in those days of actually obtaining the lumber, tools, etc. to build your own home, it seems likely that many people in this area may have taken advantage of the Sears Catalog Homes. Being close to a railroad would make it much easier to transport the materials to the building site.

Home kits were offered by other companies such as Montgomery Ward and Aladdin, but Sears was the most successful at marketing the homes. One advertisement claimed that a new Sears home would improve the health and moral character of its owners. Bathrooms were often optional – the site where the home would be built would have to have the necessary utilities in place. No problem however, Sears also sold a dandy outhouse.

After the depression in 1929, it is said that the mail order home business began to decline, and many families lost their homes to foreclosure. Sears, Roebuck, and Co. had also offered mortgages.

Identifying these homes is a difficult task. The lumber was “sometimes” numbered on each end according to the home plans. Many homes have now been remodeled or torn down. Approximately 1000 of these homes built across the United States have been identified—this is a small percentage of the total sold and built. The sources for this article listed below may be helpful in identifying a home as one from the Sears Catalog.

If anyone has knowledge of a Sears Built Home within Fayette County, please consider sharing the information with the historical commission.

Sources for the above information: “The Houses that Sears Built” by Rosemary Thornton and “Houses by Mail “ by Katherine Stevenson and H. Ward Jandl.

Sengelmann Brothers

by Connie F. Sneed

Among the thrifty and enterprising business men of Schulenburg were many who came from substantial German stock, and prominent among this number were Charles and Gustav Sengelmann, who were leading dealers in choice wines and spirituous liquors. They were the sons of Henry Sengelmann, Sr.; they were both born and reared in Sprenge, Holstein, where they acquired their early education.

Hans Henry Sengelmann, Sr was born in Germany on the 26th of October, 1820, and, having spent his entire life in the fatherland, died January 14,1907. In Sprenge, which was also his birthplace, he learned the trade of a shoemaker when quite young, and made that his life occupation. He took an active part in the revolution of 1848 and was one of the five survivors of the war in his locality. He reared five children: Henry, Johanna, August, Charles, and Gustav. Of these Henry and Johanna never left Germany. August and Charles came to Texas when they were both young men, and from 1876 to 1887 were engaged in business together.

August and Charles Sengelmann resided with their parents until August was seventeen years of age, attending the local schools. Immigrating to Texas , they first located at Columbus , where they were employed by their uncle, Henry IIse. Industrious and economical, they saved their earnings and in 1876 settled in Schulenburg, where Charles became actively engaged in business.

In 1885 August Sengelmann returned to Germany to visit his father, and on coming again to America brought with him his brother, Gustav, to whom he sold his interest in the business in 1888 and went back to the old country. He was a man of much business ability, enterprising, and energetic, who became the proprietor of one of the leading hotels of Kiel , a seaport of Schleswig- Holstein, and he operated a large and profitable business until his death in an automobile accident on July 13, 1905. His wife and four children remained in Kiel .

In 1893, the business owned by Charles and Gustav Sengelmann was destroyed by fire. In 1894, they erected a large, handsome, and substantial two story brick building on one of the finest blocks in Schulenburg.

In 1879, Charles Sengelmann married Elizabeth Arnim, who was a native of Texas , born in Moulton, Lavaca County, a daughter of A.A. and Von (Schaste) Arnim. Mr. and Mrs. Sengelmann were the parents of the following nine children: Henry, Wally, Minnie, Molly, Charles, Lillie, Alexander, Klondike , and Hester.

Like his brothers, Gustav Sengelmann received excellent educational advantages in his youth. As previously mentioned, he came to the United States with his brother, August, in 1885, succeeding him in business and becoming an active member of the firm known as the “Two Brothers”. He was once closely identified with the industrial and mercantile interests of Schulenburg. Gustav Sengelmann's wife was formerly Bertha Sommer, who was born in Schulenburg, a daughter of Ferdinand and Augusta Sommer; her parents were both natives of Germany. Three children were been born of this union: Gustav Jr, Silva, and Wilbur.

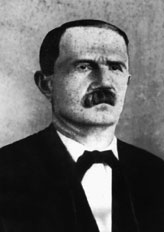

Both Charles and Gustav Sengelmann were members of the Sons of Hermann. Charles was also identified with the Ancient Order of Workmen. He took great interest in civic affairs and for a number years served as alderman.Recollections of Charles Sengelmann, Sr.

by Carolyn Heinsohn

The following article, “Six Shooter Days and History”, was written by Charles Sengelmann, Sr. and published in the October 5, 1929 issue of the Schulenburg Sticker. It was found in the collection of newspaper clippings that the late Norman Krischke of Schulenburg had saved in multiple large scrapbooks that were donated by his family to the Fayette Heritage Museum and Archives.

The following article, “Six Shooter Days and History”, was written by Charles Sengelmann, Sr. and published in the October 5, 1929 issue of the Schulenburg Sticker. It was found in the collection of newspaper clippings that the late Norman Krischke of Schulenburg had saved in multiple large scrapbooks that were donated by his family to the Fayette Heritage Museum and Archives.

Charles Sengelmann, Sr. and his brother, August, emigrated from Holstein, Germany to Texas in 1871, first locating at Columbus. In 1877, they moved to Schulenburg, a new town built on the railroad line. They opened their first saloon there in the late 1870s. Another brother, Gustav, emigrated in 1885 and purchased August’s interest in the saloon in 1887. August then returned to Germany.

After the building that housed their saloon burned in 1893, Charles and Gustav built an impressive two-story brick building on Main Street. A saloon on the first floor, known as the Two Brothers Saloon, featured fine liquors, wines and cigars, as well as billiard tables, reading tables with a line of newspapers for entertaining the patrons and first-class cuisine. A large hall upstairs was used for public balls, meetings, theatrical performances and other types of entertainment. Today, the building not only houses a restaurant and full-service bar with live music, but also serves as a wedding venue.

Senglemann’s recollections were from the first twelve years of his life in Texas: “In the olden days of the eighteen-seventies, cowboys had this country ‘grabbed’. Our officers had very little to say. Everyone carried pistols. No one was arrested for this charge. Cattle and horses were not safe; one had to chain them to log, house or stakes.

Some people made it a business to find horses and cattle for a reward for $25 or more. In those days the Americans owned the land in big sections. Old Grandfather Franz Russek built an immigration house on the railroad track. He would go to Galveston and take charge of a shipload of emigrants and bring them here. He was agent for Corres [Karesch] and Stotsky of Bremen.

After the railroad was finished to San Antonio a man by the name of Haskel, a brickyard owner in Columbus, chartered a special train. He then engaged the celebrated professor, F.A. Rose band, of which I was a member. He paid us $50 and our dinner at the Menger hotel in San Antonio. He also invited the High Hill band to accompany the train to San Antonio; but this band was not paid, and its members had to take their lunch pails along. So many tickets were sold by Mr. Haskel that there was not room for everyone to be seated. The aisles were filled to capacity and even the tops of the cars. After the train passed Welder [sic], all of the tough cowboys from Gonzales and surrounding sections had a big time target practicing, shooting at the telegraph poles and rabbits in nearby fields. One man from Weimer [sic], who was considered quite bad in these parts at that time, had his wife on the train with him. He demanded that the cursing in the car be stopped. Instantly, a dozen or more pistols were thrown in his face, and he was ordered out of the car. He left in a hurry.

At midnight the train left San Antonio for home. Owing to the condition and toughness of the passengers, the conductor hid until the train was well underway, because the cowboys, finding no seats, knocked the glass doors and windows out of the cars with their pistols. Shooting never stopped until we got home.

As the train stopped in different towns to discharge passengers, some would run to nearby saloons, only to find their train leaving them. They would curse and shoot at the train, but to no avail. This was my first and last excursion.

The city council was, mayor, old father Henderson, Dr. Walker, and Carrol Upton’s father-in-law, who endeavored to get order in the city. They hired Mr. Jamison, a fearless man. He restored order in a short time. Before order was maintained, it was necessary for him to shoot and stab some of the bad men.

We had a chance one time to get the roundhouse from Columbus, but they wanted $30,000 bonus. A mass meeting was called in the Turner Hall. All of the citizens attended, but the deal fell through on account of not getting up the money, so the shops were moved to Glidden.

In olden times the railroad paid its employees in red and black chips of 25 and 50 cent denominations, or so called meal tickets, good in any store or business house. They were also good for paying freight charges. [See note below.]

The railroad park was formerly kept up by the citizenship. Before being made into a park, however, this land was a ditch, ten to fifteen feet deep. About 150 convict workers were used to fill it up. Christian Bamgarten [Baumgarten] planted the big live oak tree which still furnishes shade.

Early railroad workers were all Irishmen. They were paid $1.25 per day.

The Bamgarten [sic] oil mill was built in 1883. At that time the cotton seed hulls were used for fuel in the oil mills.

In High Hill there was a brewery, owned by Aug. Adolf and Moritz Richter. They also had a Turner Hall and theatre, owned by stockholders. This was the only hall within a radius of 50 miles, with the exception of the old Baring Hall at Schulenburg, now the Southern Produce Co., which at that time was rented by C. & G. Senglemann, who operated the finest bar in town.”

Note from Ken E. Stavinoha:

In his seminal work "A History of Texas Railroads", S. G. Reed mentions this event which I am quoting directly from pages 193-4 and adding clarity in brackets where needed:

'Another difficulty [in the construction of the Galveston Harrisburg & San Antonio westward from Columbus] was in making change to pay off the day laborers. There was a great scarcity of small change. The

Government had called in most of it [while switching from the silver standard back to the gold standard]. To meet this [need] General Manager H. B. Andrews paid the men off partly in gutta percha tokens about the size of a quarter [having] the value of 25 cents "good for meals" and which he agreed to redeem in full. These passed current at par not only at boarding houses but in stores all along the line until

several years after the road was completed. It was a common saying at the time that [GH&SA President Thomas] Peirce was the only man who was smart enough to build a railroad with meal tickets.'

Photo Captions:

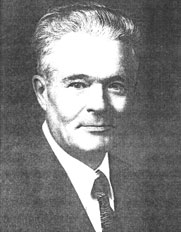

Top:

Charles Sengelmann, Sr.; from the Schulenburg Sticker, Oct. 5, 1929

Lower: G. H. S. & A meal token, courtesy of Ken E. Stavinoha

Sources:

Lotto, F. Fayette County, Her History and Her People; Schulenburg, TX, Sticker Steam Press; 1902

Sengelmann, Charles, Sr. “Six Shooter Days and History”; Schulenburg Sticker, October 5, 1929

Services, Trades and Occupations of By-Gone Days

By Carolyn Heinsohn

New inventions and technology, changes in our lifestyles, disposable commodities and the need for “instant gratification” have all contributed to the disappearance of certain services, trades and occupations, some of which were needed for daily living in the past. These services and occupations unfortunately have faded away into the annals of history. However, some senior citizens still have memories of the people who provided these necessary services and products that were not readily available elsewhere due to a number of factors. Transportation was slow, stores that could provide the needed supplies were few and far between and sometimes understocked, and the time that it took to seek out a source for those services and items meant time away from one’s work, so anyone who could fulfill those needs was truly appreciated.

New inventions and technology, changes in our lifestyles, disposable commodities and the need for “instant gratification” have all contributed to the disappearance of certain services, trades and occupations, some of which were needed for daily living in the past. These services and occupations unfortunately have faded away into the annals of history. However, some senior citizens still have memories of the people who provided these necessary services and products that were not readily available elsewhere due to a number of factors. Transportation was slow, stores that could provide the needed supplies were few and far between and sometimes understocked, and the time that it took to seek out a source for those services and items meant time away from one’s work, so anyone who could fulfill those needs was truly appreciated.

In the 19th century, there were “pack peddlers” – men who virtually carried mini-general stores in their wagons. They sold everything from sugar, flour, salt, pepper and spices to pots and pans, utensils, small tools, nails, shoes, hats, fabrics, laces and ribbons and all things in-between. Occasionally, there were also women, usually older single or widowed women, who traveled around selling millinery supplies, women’s corsets, bustles, shoes, dressmaking supplies, plus rose water and castile soap, which was much preferred over homemade soap for face washing and shampooing.

Before mass manufacturing of shoes, one went to a cobbler to purchase custom made shoes. Every family, however, generally had shoe forms, tack hammers, awls and shoe tacks at home with a supply of shoe leather, soles and heels with which to do minor repairs. As time moved on, one went to the local shoe shop to have soles and heels replaced or other repairs made to shoes and leather items. Now shoes are discarded instead of repaired, and shoe repair shops are difficult to find.

Of course, every community had one or two blacksmiths who made and repaired anything made of iron. Horseshoes, plowshares, branding irons, tools and wagon wheels were always in demand. Many times, a farmer would learn the trade for his own personal needs, as well as providing for the blacksmithing needs of his surrounding neighbors, especially when a blacksmith shop was too far away to be convenient.

Before the era of electric refrigerators, people who owned ice boxes had to regularly replenish their blocks of ice. A placard was placed on the front screen door to alert the ice man who drove throughout town looking for potential customers. He brought in the dripping block of ice with large tongs and placed it in a small metal receptacle in the ice box. If additional ice was needed for cooling beverages or making homemade ice cream, people went to the local ice house to purchase a block of ice. There was no ice crusher – an ice pick and elbow grease did the job!

There was an elderly black man who lived in La Grange who was a “pot tinker”. In the 1940s and early 1950s, he drove a wagon pulled by mules throughout town looking for interested customers. He would actually repair holes in pots, buckets and other containers, mostly graniteware and enamel, which were more likely to develop holes where chips had occurred. He also sharpened scissors and knives and did other minor repairs of household items.

Some traveling salesmen in years past were sources of convenience items that made lives easier. They also provided medicinal products that could potentially save a trip to the doctor. The Watkins Products salesmen sold extracts and spices, as well as liniments, tonics and salves that could be used on humans and animals. Many of the early Watkins salesmen had wagons, some of which were enclosed, with the Watkins logo painted on the sides, so that they would be easily recognized as they approached their customers. Later there were also Fuller Brush salesmen, who had a wide selection of brooms, mops, brushes, dusters and other cleaning tools, and the Stanley Products sales persons, who provided an assortment of cleaning supplies and tools. There were door-to-door vacuum cleaner salesmen, as well as those who sold “waterless” cookware, encyclopedia sets, greeting cards and Bibles.

People who lived in cities also had the “luxury” of having milk and eggs delivered right to their front doors. Sometimes, homes had small insulated boxes on the front porches where the milk and eggs could be placed to keep them cool until picked up by the homeowners. In fact, some of these deliverymen were so trusted that they were allowed to enter unlocked homes unannounced to place the milk and eggs directly into the ice boxes or refrigerators.

When mail order companies like Sears and Roebuck and Montgomery Ward were created, they provided a tremendous source of readily available manufactured products, including furniture, heaters, cook stoves, washing machines, clothing, dishes, tools, musical instruments and decorative items. They even offered all of the materials needed to build houses, some of which are still standing. The general merchandise mail order companies all contributed to the eventual decline of the pack peddlers and door-to-door salesmen.

Most of these services from by-gone days are now nostalgic memories for senior citizens and unknown entities to the younger generation, who cannot comprehend anything that is not disposable, purchased at a mall, a “big box” store or ordered online.

Photo: Watkins Products Salesman from Carolyn Heinsohn's postcard collection.

Enterprising Settlers

— John and Michael Short —

by L.J. CalleyYou may have the impression by now that Fayette County in the 1830s and 40s was a far different community than it became after the major immigrations of the Czechs and Germans. Certainly Fayette County and its largest settlement, La Grange, had a devil's share of Anglo-American frontier types with colorful to dubious histories.

Today's article is about two more individuals of this ilk. Michael and John Short arrived in Texas in 1835 by way of Georgia and Alabama and joined Sam Houston's army in time to fight in the battle of San Jacinto. They soon located in the Muldoon area where they farmed, operated a mill, and generally made themselves unpopular by openly championing the abolition of slavery. At this time, the largely non-slaveholding German and Czech farmers were still a small minority. The brothers soon began an Underground Railroad that encouraged fugitive slaves in their efforts to move north.

A pair of the county's finest, most principled citizens, right? Wrong. It seemed that the slave runaways were always getting caught and resold, over and over again. Although never proven, rumor had it that the Shorts were getting long on money on each transaction. What the slaves may have gotten for their complicity is not known

Things were going so well that the brothers, with the help of younger family members, decided to diversify into cattle theft and later, counterfeiting. According to "The Huntsville Banner" their counterfeiting ring involved five states. Two relatives were tried and convicted for these activities. Michael's nephew, William, was hanged on October 6, 1849, and John's son-in-law, William Sansom, had the dubious distinction of becoming the first inmate of the recently completed state prison at Huntsville.

John Short died in 1847, and Michael died in 1859, both of natural causes. Michael and his wife, Permelia, and their two sons are buried in the old City Cemetery in La Grange. Prior to her death in 1867, Permelia Short lived at the corner of Travis and Crockett Streets, where H.E.B. is now located.

Today, Fayette County is known for its civic-minded citizens and peaceful, quiet orderliness. My, how things change.

Side-Wheelers on the Colorado

by Larry K RipperToday we think of the Colorado River as a gentle stream that meanders on its way through our town. For a brief period in our States history, however, it offered up the prospect of commercial river traffic and a future for a fledging, landlocked economy.

In 1840, William McKinstry published The Colorado Navigator, which was a full description of the "bed and banks" of the river. He believed that the Colorado could support commercial river traffic. Early traders in keelboats moved produce and provisions between settlements, but the lack of power made these boats ineffective against the slow but steady current.

In 1844 The Republic of Texas chartered the Colorado Navigation Company for the purpose of developing navigation on the river. Later that year, the first steamboat on the river was built at La Grange. The Kate Ward, a sidewheel steamer, had twin seventy horsepower engines. She was 115 feet long and 24 feet wide. Built to draw only 18 inches of water empty, she was capable of carrying 800 bales of cotton. In 1848, a similar craft, the Water Moccasin, was constructed at Bastrop.

The river offered many challenges to navigation; sandbars, rocks, log "snags", and low water were ever-present dangers. Three miles upriver from La Grange, boatmen would face the infamous Rabbs Shoals, a section of fast water and rocks. The greatest obstacle, however, was the "raft" at the mouth of the Colorado near Matagorda. There stood a massive logjam, which completely blocked the path to the Gulf.

After about 15 years of commercial steamboat operations, improved roads and the promise of railroads, along with the frustrations of an ever-changing river, contributed to its demise. Low water would ground boats for months; however, with good water they would make Austin. Next time you're on the river…listen carefully. That sound you hear just might be the echo of the Kate Ward's whistle as she steams round the bend with her homeport in sight.

Julia Lee Sinks

by Annette RuckertJulia Lee Sinks – a pioneer settler, historian, and author – wrote, "Folklore constitutes the only basis of history in the settlement of a new country—.I have let those as near as possible who have made this history write it themselves."

Indeed, as noted by Lonn Taylor in the book's foreword, Chronicles of Fayette is not so much a narrative history as a collection of sources, "a group of voices from Fayette County's past, recording their own experiences."

But it was Julia Lee Sinks who gathered these sources, who brought the voices together to tell a story. With her talent for writing, which she called a "taste for scribbling and recording," Sinks helped preserve the history of Texas and Fayette County.

A "loyal, enthusiastic, and valuable supporter," Sinks was a person whose "character and influence…manifested those high ideals of womanhood which were the finest products of the Old South," said The Quarterly of the Texas State Historical Association in April 1905.

Men respected Sinks and encouraged her to participate in various historic preservation projects - at a time when business and public meetings did not often include women. Though not a native Texan, Sinks revered Texas and respected the settlers who arrived during the Republic and early statehood periods.

Sinks was born on January 18, 1817, to George and Mary (Morse) Lee. In early 1840, her family left Cincinnati, Ohio, to settle in Austin, the newly selected capital of Texas. There she met George W. Sinks, the chief clerk of the Post Office Department of the republic. They married in 1841. In 1842, they moved to La Grange, where George Sinks pursued a career as a merchant. The couple eventually became parents of six children.

Julia Lee Sinks did not limit her activities to child rearing and housekeeping. She collected rocks and minerals, wrote stories and poems, and corresponded with well-educated friends. People who believed strongly in the success of Texas introduced Sinks to the Republic. Soon she began her new interest - preserving the history of Texas and the story of its heroes.

Her role in creating a burial site for the men who died in the Dawson Massacre of 1842 and the Mier expedition is an example of her efforts to preserve Texas history. At the dedication of the Monument Hill site in 1848, Sinks covered the coffins with black cloth and draped them with black velvet, clusters of leaves, and stars - decorative trimmings prepared with her own hands.

The preservation of Monument Hill continued to interest Sinks throughout her life, and she dedicated herself to establishing facts, writing articles, and raising funds to build a monument at the burial site.

In 1876, a Centennial Committee of seven prominent La Grange citizens decided to gather a history of the settlers of Fayette County. They agreed that Sinks should be the woman to write the book.

Sinks collected oral and written histories from many early settlers and their descendants. She included some of her personal experiences, as well. She also gathered information on topics such as pioneer life and the characteristics of early Texans, Indian battles, social institutions, transportation, cemeteries, and county organization.

Although parts of her manuscript appeared in newspapers and journals, the book remain unpublished until 1975. The Heritage Committee of the La Grange Bicentennial Commission published several hundred copies of Chronicles of Fayette as their first project. In 2000, the Fayette County Historical Commission reprinted the book in its original form.

Julia Lee Sinks died on October 24, 1904. According to the Handbook of Texas, she was a member of the Texas Veterans Association and was a charter member, vice president, and honorary life member of the Texas State Historical Association.

Her scrapbooks and journals contain handwritten copies of poems, short stories, religious writings, letters, and historical notes. Through the years, she contributed many of these items to various newspapers and journals. The University of Texas received her collection of miscellaneous documents relating to the history of Texas from 1837 to 1900.

An eventful life as a pioneer settler, a desire for historical accuracy, and a gift for writing - all served Julia Lee Sinks well in her effort to preserve Texas history. And her reminiscences in Chronicles of Fayette serve us well today, reconstructing for us our background - telling our story - through the voices of the past.

Sally Skull

by Sherie KnapeThere have been many legendary female characters throughout Texas history and the most infamous was Sally Scull (Skull). Sally was born Sara Jane Newman in 1817 or 1818 probably in Illinois. She was the daughter of Joseph Newman and Rachel Rabb Newman. Her grandfather, William Rabb, moved his entire family - children, grandchildren and all - to a Spanish land grant site in now present-day Fayette County where he was a gristmill operator.

The women often found themselves at the mercy of the wilderness and the Indians when the men were away. Sally probably inherited her strength of character and spirit from her courageous mother Rachel. Legend has it that during one of Joseph's frequent absences; Comanches attempted to enter the Newman cabin. Rachel took offense and promptly chopped off one of the Indian's toes with a double bit axe. The Indians then tried to enter the home by way of the chimney. A feisty Rachel piled feather pillows in the fire grate and set them ablaze.

In spite of Rachel and Sally's well-earned reputation for self-defense, Indians of other tribes continued to raid the Newmans at every opportunity.

Eventually Rachel complained enough to her husband about the Indian raids that the Newman clan fled their initial settlement and took up residence approximately fifty miles southeast in the safer climate of Egypt about ten miles north of Wharton.

In 1833 Sally married Jesse Robinson. The couple moved into their house on Jesse's land grant near Gonzales. In March of 1836, Sally and her two-year old daughter very likely got caught up in the Runaway Scrape as citizens fled before the invading armies of Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna.

In 1843 Jesse Robinson sued for divorce. He called his bride "a great scold, a termagant, and a adulterer." Sally countered and charged Robinson with cruelty and claimed that he'd squandered her inheritance. She wanted her dowry restored and custody of their two children, nine-year-old Nancy and six-year old Alfred. The jury split up the property but failed to render a verdict on the children. The couple's divorce was finalized on March 6, 1843. Later Sally placed the children in a Catholic School in New Orleans.

Within a heartbeat of Jesse's departure from her life, Sally remarried. The groom was George H. Scull, a mild mannered gunsmith. He and his new wife moved back to Egypt and lived on land inherited by her father. Although she remarried three more times, Sally retained the name Scull or Skull for the rest of her life.

For 5 years Sally Skull seemed to drop off the face of the earth only to reappear claming herself as a single woman. When asked on the whereabouts of her sweet natured, mild mannered husband, she snapped, "He's dead." Evidently no one cared or had the nerve to question Sally so poor Scull just passed into history.

For a few years Sally roamed the countryside. In 1852, she turned up in Banquete and bought a ranch. She married John Doyle and they started a highly successful trade and livestock business. Not long after arriving in the area she was involved in a pistol fight. The shooting took place in front of numerous bystanders and might be the reason for her quickly growing reputation of violence. The entire population of South Texas was said to recognize her as she rambled across the land with her mule trains and horse herds. She wore mostly pants even though it was considered unnatural for women. For formal occasions she hid two French pistols under her clothing but for everyday wear a gun belt and heavy revolvers worked fine.

Sally persuaded her cousin, John Rabb, and his friend to acquire land next to hers and they began running huge herds of cattle under the now famous Bow and Arrow brand. She traveled around the countryside acquiring livestock alone and carried large amounts of gold in a bag hanging from her saddle horn. Concerned family members warned her that such practices could be deadly. Sally just laughed, checked her loaded pistols, and continued on her way. Whispered rumors of horse theft often followed Sally, but no one had grit enough to accuse her openly.

Sometime between 1852 and 1855 John Doyle faded from the scene. Having two husbands vanish left neighbors with wild stories of how she must have killed one or both of them.

It is fairly certain that she didn't kill her fourth husband, Isaiah Wadkins. Her petition for divorce described a physically and mentally abusive union that ended when she abandoned him in 1856 after he beat her and dragged her behind a horse.

When the Civil War broke out, Sally had been living with her fifth and final husband for over a year, Christopher Horsdorff, at least twenty years her junior. During this time she stopped ranching and began the more profitable business of running cotton from Texas to Mexico and returning with weapons for the Confederacy. This added to Sally's already legendary status.

When the Civil War ended Sally again dropped out of sight. In 1867, a suit filed against her in 1859 ended with the puzzling note "death of Defendant suggested." Many believe Horsdorff killed her for her riches. Authorities never brought charges against Horsdorff or anyone else. Legends still persist that she simply abandoned her old stomping grounds and struck out to find a new life.

In the end it doesn't really matter how or when Sally Skull died. Her life of struggle, achievement, defeat, and success in spite of unbelievable odds should be what we take from her story. Sally Skull was never known to betray a friend and even during the rough times she still maintained close contact with her son and daughter. And although parents all over used the image of Sally Skull to keep their offspring from misbehaving, there is no evidence that she was anything but loving and concerned when it came to any child she ever met. In 1964 a historical marker in her honor was erected two miles north of Refugio, Texas

Mollie E. Hodge-Smith and J. Frank Smith

Winchester (Fayette County) and Doaks Spring, Texas Pioneers

By David L. Collins, Sr.

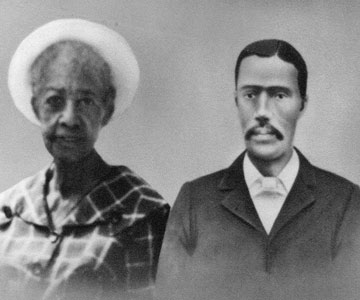

Mollie E. Hodge, the daughter of Henry Hodge and Georgianna Hodge, was born in May 1870 in Winchester (Fayette County), Texas. Her brothers and sisters included W.E., E.M., Clara, Valdie and T. H. based on the 1880 census. Mollie’s father, Henry, was from Tennessee, and her mother, Georgianna, was from Maryland.

Mollie E. Hodge, the daughter of Henry Hodge and Georgianna Hodge, was born in May 1870 in Winchester (Fayette County), Texas. Her brothers and sisters included W.E., E.M., Clara, Valdie and T. H. based on the 1880 census. Mollie’s father, Henry, was from Tennessee, and her mother, Georgianna, was from Maryland.

Before we get into the incredible story of Mollie and Frank, we want to go back to the birth of her mother, Georgianna Hodge, who was born in 1835 in Maryland and according to census records belonged to the Browning and Cracksaw Estate. They owned a rope factory on Light Street in Baltimore, Maryland. Georgianna was sold at a Sheriff sale for debt when she was 16 years old in 1851. Once Georgianna was sold, the new owners apparently used her as a personal servant. This assumption is based on a travel manifest in which she arrived back in the United States on December 14, 1863 from Aspinwall, Panama. The passenger list showed her name as Georgianna Hodge, born about 1835, female, ethnicity - American, place of origin and destination - United States of America, port of arrival - New York, New York, and traveling on the Steam Ship Illinois.

Georgianna’s name was listed below J. Perry (merchant), Mary Perry, George L. Perry, Ellen T. Sealey, and below her name was A. S. Meade and Mary Hatch, both females. One can only assume that Georgianna was a servant to the Perry family or one of the other merchants who traveled on that same ship.

Georgianna’s future husband, Henry Hodge, was born in Tennessee in 1827 and by November 10, 1870 (enumeration date) was in Beat 1, Fayette County, Texas, USA, involved in agriculture.

Winchester (Fayette County), Texas

By 1880, Henry Hodge (age 53) and Georgianna Hodge (age 45) were living in Winchester, Texas and raising a family of six children. The census shows that their oldest child, W.E., was born in 1858 in Texas, and their second child, E.M. was born in 1866. W.E.’s birth year dictates that he was born prior to emancipation, indicating that the Hodges must have come to Texas with their owner. Apparently, Georgianna traveled with her owners in 1863 prior to her second child being born in 1866.

Migration to Lee County, Texas