Footprints of Fayette

These histories were written by members of the Fayette County Historical Commission. They first appeared in the weekly column, "Footprints of Fayette," which is published in local newspapers.

Lancelot Abbotts

by the Fayette Heritage Archives Staff

Lancelot Abbotts was born in England in 1812 and emigrated to Texas in January 1835. He worked as a printer and a clerk at San Felipe until he joined the Texas army in February 1836. Abbotts served as a camp guard during the Battle of San Jacinto. For this service he was awarded a donation certificate for 640 acres of land in 1841.This land was located in Austin County. In March 1849 Abbotts bought the William Toy League of land in present southwestern Fayette County. According to the July 1850 Federal Census of Fayette County Abbotts was now employed as a printer by the newspaper in La Grange known as the Texas Monument. Abbotts was also listed as being married on that census but it is unclear when he was actually married. Abbotts and his wife, Elizabeth, built a large home on his league of land about 1857 and raised sheep. It was a profitable if unusual business for this area. In 1860 his flock of sheep yielded 620 pounds of wool. Sometime between 1868 and 1870 Abbotts returned to his native England. His cousins, the Thomas Carter family were occupying the Abbotts home in 1870. There were several rumors as to why Abbotts left Texas including one of the more colorful ones that speculated that he had inherited land and a title in England which required him to give up his land holdings in Texas. In an 1874 letter to his old friend, Moses Austin Bryan, Abbotts states that he "has not willingly left Texas." He also states that he gave away his land in Fayette County to his nephew's family and that he gave away his other land to the relatives of his wife because he felt bound to give something to her family because he could not give it to her as she "has left me to weep." Abbotts never returned to Texas. He told Bryan that he would have done so the following spring had his wife not died. Lancelot Abbotts is best known in Fayette County for the house that he built. It is a three-story stone house constructed on an exceptional site. The orientation of the house creates a cooling breeze. The thickness of the walls retain heat in the winter while keeping it cooler in the summer. At present, part of the house still stands.

Melvin Adamek

At Home in Schulenburg—Vet Still Wonders How He made Parade Detail

A reprint from the Houston Post newspaper – March 5, 1953, submitted by Ed Janecka

By I.E. Clark - Post Staff Correspondent

SCHULENBURG, March 4 –

President Eisenhower may have pinched himself a time or two during his inauguration to make sure it was really happening.

Sgt. Melvin Adamek of Schulenburg was black and blue from pinching himself.

A FEW WEEKS earlier, if Adamek thought anything at all about the inauguration between rifle shots on the Korean front, he didn’t think he’d be there.

Now he is back in Schulenburg, a civilian again, with vivid memories of marching in the inauguration parade.

Adamek was one of the 98 Korean veterans who formed the honor guard for the President.

He doesn’t know how he was selected.

“I was on the front line,” he said. “I had been up all night, and around 6 AM I went to bed without any breakfast. At 8 o’clock a guy came in and told me to get up – S-1 wanted me.

“THAT’S ALL he said, and I wondered what I was in for now. They asked me a bunch of questions and then told me to come back at 12 for a special detail on the east coast back in the States. I didn’t know what it was all about until I got to division rear.”

Adamek said the honor guard was chosen from men fighting in Korea with the grade of sergeant or better, height of 6 feet or more, a clear record, and who were due for rotation or separation.

How the 98 were picked from all the men eligible, Adamek does not know.

THE HONOR GUARD was composed of three men from each Army and Marine regiment serving in the Far East Command – a color bearer and two rifles to the colors.

Adamek was not a regular color bearer and he had to learn that job at Eighth Army Headquarters at Seoul. On Dec. 22 he was sent to Japan.

“Christmas in Japan wasn’t like Christmas at home,” he said, “but it was a heck of a lot better than Christmas on the front line.”

After six days in Japan the 98 men were put on a ship headed for the States. The picture of the honor guard printed in the Jan 26 issue of Life Magazine was taken in Japan, he said.

“WE WERE TREATED royally in Washington,” Adamek said. “The USO took us on a tour of Mount Vernon, the White House, the Capitol, museums, and other buildings. It was certainly interesting.

“But the most impressive thing about the whole deal was the remarks we heard from the people as we walked down Pennsylvania Avenue in the parade.

“All the way you could hear mothers saying, “There go our boys.” You know they didn’t mean you in particular, but the guys you were representing – the ones you had left in Korea. A person kind of felt like crying.”

Adamek returned to Schulenburg and was separated from the Army after serving two years. He had spent six months in Korea as squad leader of a rifle company with the 24th Infantry Regiment in the 40th Division. Before going to the front he worked with Communist prisoners on the Koje Island.

ON THE FRONT he went out on patrol about every fourth night.

“I can only say I’m glad I didn’t have to stay any longer,” he said. “It all seemed so useless over there.

“The position I was in, they had been sitting there two years – just patrolling back and forth and getting guys killed every night. If they keep on going the way they have that thing will last a 1,000 years. It’s disgusting.”

Adamek believes most of the men would rather push forward and try to end the war.

“IT WOULD BE ROUGH making a push, but I don’t believe we’d lose any more men, and it’s a cinch they aren’t accomplishing anything this way.

“Most of the boys believe that a settlement would be reached sooner by pushing on through and getting the Communists out of Korea. It wouldn’t be easily done, but at least we’d be getting somewhere.”

Korea is the bleakest, least interesting place he has ever seen.

“NOTHING BUT HILLS,” he said. “There’s one hill, and then another hill behind that, and then the next hill is still higher.”

Adamek hasn’t decided what he’s going to do now that he is out of the Army. He had thought about going back to farming near Schulenburg, but he hasn’t’ been able to find a suitable place.

“One thing is sure,” he said. “I’m already tired of sitting around doing nothing.”

Twenty-four years old now, Adamek farmed with his father, Emil Adamek, on the family farm two miles north of Schulenburg on Highway 77, after graduating from the Saint Rose Catholic Elementary School here until he was drafted into the Army.

Adolph and the Boys

by George Koudelka

During the heyday of Texas Polka Music in the 1930s, one Fayette County Orchestra became known statewide through its radio programs, recordings, and live performances. Originally known as Adolph and the Boys, the group later changed their name to reflect their sponsors.

It all started in 1935, when Julius Pavlas, an old-time musician and Engle resident, entered his band in a contest at the Majestic Theatre in San Antonio. They took first place. The band came to the attention of Universal Mills, a large Texas flour producer, who invited Mr. Pavlas and his band back to San Antonio for an audition. Many of his band members refused to go, so Mr. Pavlas had to hurriedly round up new musicians, plus an announcer who could handle network radio broadcasting. He invited Johnny Luecke, an electrician and ham radio operator, to be the announcer and Tom Hinton of Weimar as sound engineer.

The musicians added came from Lee Prause's band from Schulenburg. After considerable practice and an audition, the band was accepted for network performance. The first program went on the air on November 3, 1935 and was sponsored by Goldchain Flour. The band was known as Adolph and the Goldchain Bohemians.

The band wore original Tyrolean costumes and broadcast live from the stage of the Cozy Theatre in Schulenburg. The programs ran from 8 to 8:15 each weekday morning and Sunday afternoons from 3 until 3:45. The program was carried over TQN (Texas Quality Network), which included stations WOAI in San Antonio, KPRC in Houston, and WFAA and WBAP of Dallas-Fort Worth. The audio was transmitted over telephone lines.

During this time the band made a number of 78 rpm recordings on the Okeh and Vocalion labels. These recordings were later re-released on the Columbia Red label.

The band consisted of nine members, among which were Herbert Kloesel and Lee Prause of Schulenburg; Charlie Rainosek of Weimar; and Arthur Kloesel of Hallettsville. Scott Kirsch, a violinist with the Houston Symphony, helped with the band's tuning and balance. Henry Kubala, of St. John, was the solo clarinetist. Buddy Heyer, the pianist, wrote many of the band's arrangements.

The last radio broadcast of Adolph and the Goldchain Bohemians was heard on the last day of May in 1937, thus ending an era of musical history for Schulenburg and Texas Polka music.

The Seelig Alexander Family of La Grange

By Carolyn Heinsohn

There already was a Jewish presence in La Grange by 1851 when Seelig and Bertha “Bertie” Rosenfield Alexander arrived. They followed her brother, John Rosenfield, who arrived in Texas in 1844. Then Gabriel Friedberger arrived; he owned a dry goods store on the downtown square in the 1850s and was later involved in the cotton trade during the Civil War. Julius Cohen was a peddler, and Bernard Zander, who moved to La Grange in 1859, owned a saddlery. Seelig’s older brother, Abram, arrived in La Grange in the late 1850s. All of these early Jewish residents were Prussian born and involved in retail trade. Throughout the decades, more Jews arrived; however, the best-known were the Alexanders, especially Abram’s family, some of whom lived here much longer than the others.

Seelig “Sam” Alexander was born in 1826 in Thorn, Prussia, now Torun, Poland, the son of Sprinze Seelig and an unknown father. Listed as a shoemaker, he immigrated to the United States with his wife from Wiszig, Germany, arriving in New York City in 1850; they stayed in the city for a year and then moved to La Grange. Sam’s actual name was Alexander Seelig, but when he entered this country, an immigration official recorded his name in reverse. When his brother, Abraham Seelig, emigrated, he kept the Alexander surname to avoid further confusion; thus, he became Abram Alexander. Sam was listed as a grocery merchant in La Grange in the 1860 census, when he and Bertha were next door neighbors to her brother, John, his wife, Fanny, and their four children. By 1870, John Rosenfield had moved with his family to Columbus, Texas, where he eventually owned a wholesale beer and ice company.

During the Civil War, Sam served as the Captain of Company A 4th Battalion Texas Infantry, Confederate Army. By 1870, he was listed as a dry goods merchant in La Grange.

Seelig’s mother, Sprinze Seelig Badt, and her husband, Joseph Badt, were living with Sam and his family by 1880. Interestingly, Sprinze, listed as age 93, was 28 years older than Joseph, whose occupation was sausage maker. Eventually, she moved to Austin, where she died in 1888. The inscription on her tombstone in the Oakwood Cemetery states that she was born in 1776 and died in 1888 at age 112. However, based on census records, she would have been 101, which is more plausible.

By 1884, Sam owned a wholesale tobacco and cigar business, Seelig Alexander, Sr. & Company, located on Main Street in Houston, although his place of residence was still in La Grange. He and Bertha had a total of 10 children: Gertrude (Sass), Seelig “Sam” Jr., Moris, Joseph, Rachel (Sass), Matthew “General”, Callie (Cramer), Jacob, Rosa (Heilig) and Jonas. Eventually, all of the living children left La Grange.

Moris and Jacob died as children; Joseph, who remained single, died of ulcerative colitis at age 30. Gertrude, who married Pincus Sass, lived in La Grange for a while after her marriage; however by 1910, she had moved to Seattle with her children after her husband died. They lived next door to her sister, Sallie, who was married to Max Cramer. Their single brother, General M. Alexander, lived with Gertrude for a number of years, but by 1920, he had moved back to Houston, where he worked as a dry goods salesman. Initially, his name was listed as Matthew, but later, he used the name General M. He died in a Jewish home for the aged in Memphis, Tennessee in 1948 at the age of 85. Gertrude also left Seattle by 1930 to live closer to one of her children in Dallas, where she died in 1934 at age 92. Sallie and Max Cramer moved from Houston to Seattle by 1910, where Max worked as a real estate agent and then as an automobile salesman. Sallie died there in 1940 at age 76.

Seelig “Sam” Alexander, Jr. married Hannah Cramer and was living in Houston by 1900; he worked there as a retail grocery merchant and a cigar merchant. Sam died in Houston in 1934 at age 79.

Rachel married Herman Sass in 1878. The 1870 census lists him as 18 and working as a store clerk in La Grange, where he met Rachel. After they married, they too moved to Houston, where Herman worked as a traveling salesman. Rachel died in 1909 at age 49.

Rosa married Gustav Heilig, who was an important businessman, public official and newspaper publisher in La Grange before he and Rosa moved to Dallas around 1916. Semi-retired, he worked as a real-estate agent. Rosa died in Dallas in 1952 at age 84. Jonas Alexander married Sadie Harris of Houston. They also moved to Dallas, where he worked as a traveling salesman; he died of a heart attack in 1933 at age 62.

Rosa married Gustav Heilig, who was an important businessman, public official and newspaper publisher in La Grange before he and Rosa moved to Dallas around 1916. Semi-retired, he worked as a real-estate agent. Rosa died in Dallas in 1952 at age 84. Jonas Alexander married Sadie Harris of Houston. They also moved to Dallas, where he worked as a traveling salesman; he died of a heart attack in 1933 at age 62.

Seelig “Sam” Alexander, Sr. died in La Grange on September 16, 1896 at age 70 of heart failure. His wife, Bertha, died on December 28, 1908 at age 77 of a stroke following a hip injury, based on an obituary description of conditions leading to her death. Both are buried in the La Grange Jewish Cemetery, along with four of their children: Moris (1856 – 1867), Jacob (1866-1868), Joseph (1857 – 1887) and Gertrude (1852 – 1934).

In the early 1940s, the Jewish cemetery property was sold by the Ladies Hebrew Cemetery Association to a private buyer. The cemetery records were entrusted to Abram Alexander’s grandson, Bernard Sass, of Dallas; the whereabouts of those records after his death are unknown. The cemetery with only 33 graves is now on private land between the La Grange ISD football field and the Colorado River.

Had it not been for Seelig Alexander’s decision to relocate to La Grange, the legacy of Abram’s family here would not have happened; his story is next.

Photo caption:

Seelig Alexander’s tombstone in the La Grange Jewish Cemetery; photo courtesy of www.findagrave.com

Sources:

Alexander files; Fayette Heritage Museum and Archives

Ancestry.com; immigration, census and death records; family trees

Houston City Directory, 1884

Obituaries; www.fayettecountyhistory.org

www.findagrave.com

The Abraham Alexander Family of La Grange

By Carolyn Heinsohn

Abraham Alexander, the older brother of Seelig Alexander, whose story was previously published, was born in 1823 in Thorn, Prussia. The name of his first wife is unknown, but they had two children: Cecilia, born in 1850, and Sam, born in 1852. He left his two children behind when he immigrated to New York City in the 1850s, sometime after the birth of Sam. His two children later immigrated in 1866 as teenagers with a group of persons from Thorn to Galveston. Perhaps, his wife died prior to his decision to immigrate, so he left his young children behind with relatives. In 1870, Cecilia married Stanislaus Szmiderski of noble and rich Israelite parentage. She died in 1888, leaving no children, and was buried in the La Grange Jewish Cemetery. Sam Alexander married Annie Cohen and settled in Fresno, California; they had six children, one of whom died in infancy.

Abraham Alexander, the older brother of Seelig Alexander, whose story was previously published, was born in 1823 in Thorn, Prussia. The name of his first wife is unknown, but they had two children: Cecilia, born in 1850, and Sam, born in 1852. He left his two children behind when he immigrated to New York City in the 1850s, sometime after the birth of Sam. His two children later immigrated in 1866 as teenagers with a group of persons from Thorn to Galveston. Perhaps, his wife died prior to his decision to immigrate, so he left his young children behind with relatives. In 1870, Cecilia married Stanislaus Szmiderski of noble and rich Israelite parentage. She died in 1888, leaving no children, and was buried in the La Grange Jewish Cemetery. Sam Alexander married Annie Cohen and settled in Fresno, California; they had six children, one of whom died in infancy.

Abram had previously worked in a hat factory in Prussia, so for a few years after arriving in New York City, he worked as the head clerk in a hat making establishment that employed 2000 men. He decided to join his brother in La Grange in the late 1850s, where he operated a general merchandise store until 1860, when he moved to Winchester, where he operated another retail store. Because of his popularity in that community, he was given the nickname “Winchester”. In 1863, he moved his business back to La Grange. Later that year, Abram married Dorothea Ackermann, who was born in 1846 in Kassel, Germany. She immigrated to Fayette County with her parents, Joseph Peter and Gertrude Rupersburg Ackermann, when she was eight years old. She was not Jewish, so when she married Abram and converted to Judaism, her parents disowned her. They died in the yellow fever epidemic in 1867, and thereafter, the Alexander family had almost no contact with their Ackermann relatives.

Abram also owned a factory that made hats for the Confederate Army during the Civil War. His factory, that employed approximately 100 men, was supervised by Julius Conrad Tips, who also died during the yellow fever epidemic. Some of the workers in the factory were very young Confederate soldiers, who were assigned to work there rather than fight in the battlefields. In June 1865, a large group of disgruntled unpaid soldiers from Walker’s Cavalry Division went to Alexander’s Hat Factory and either seized or destroyed all of the government property, totally demolishing the business, amounting to a $10,000 loss. The next day, another group of soldiers robbed and pillaged a number of other businesses in town, amounting to an additional $20,000 loss.

Soon after they married, Abram and Dora moved to a small four-room house with an outside kitchen in the 100 block of S. Washington Street. As their family grew, so did their house until it became a large two-story Southern-style home with tall columns, a wide porch and a beautiful interior. They reared ten children in this house: Henry (1864-1923), Harry Benjamin (1866-1929), Charles S. (1868-1933), Esther “Essie” (1871-1968), Henrietta “Hattie” (1873-1950), Victor Dunn (1877-1932), Jacob “Jake” (1879-1953), Rachel “Rae” (1882-1944), Gertrude “Gertie” (1884-1968 ), and Jeannette Cecilia (1889–1977).

Soon after they married, Abram and Dora moved to a small four-room house with an outside kitchen in the 100 block of S. Washington Street. As their family grew, so did their house until it became a large two-story Southern-style home with tall columns, a wide porch and a beautiful interior. They reared ten children in this house: Henry (1864-1923), Harry Benjamin (1866-1929), Charles S. (1868-1933), Esther “Essie” (1871-1968), Henrietta “Hattie” (1873-1950), Victor Dunn (1877-1932), Jacob “Jake” (1879-1953), Rachel “Rae” (1882-1944), Gertrude “Gertie” (1884-1968 ), and Jeannette Cecilia (1889–1977).

Abram’s general merchandise business that occupied a frame building on the corner of Travis and Washington Streets next to their home eventually became a grocery business. An advertisement in a May 1876 issue of a local newspaper stated that Abram Alexander was a dealer in fancy and staple dry goods, family groceries, lime, Calcasieu and Texas pine lumber, dressed and undressed, plus shingles made of cypress blanks to order. At one time, there were several storage buildings on his property which may have held his lumber.

Henry, the oldest son, started making candy in 1887 with the help of some of his brothers. In 1890, he purchased a lot on the corner of Washington and Crockett Streets, just south of the Alexander home, for a candy factory that employed 14 people. A year later, he renovated the building to include a retail confectionary and ice cream and soda parlor. By 1900, Henry had moved to Houston, where he married Mattie Jobe two years later; they had four children: Sam, Howard, John Lee and Dorothy. Henry’s wife died in 1919, and unfortunately, he suffered a severe burn that ultimately caused his death in 1923. He was buried in the Hollywood Cemetery in Houston. Since his wife was not Jewish, he became estranged from his siblings.

After a lingering illness, Abram Alexander passed away in March 1898 at the age of 74. He was buried in the La Grange Jewish Cemetery, but later his body was exhumed and reburied in the Alexander plot in the La Grange City Cemetery. His obituary states that he once was a wealthy man, but suffered financial reverses late in life.

Harry, Charles, Victor, Jake and Rae turned the family grocery store into a wholesale grocery business that was incorporated in 1900 as the Alexander Brothers Grocery Co. It was moved to East Colorado Street, later the site of the Pat-Mac Produce Company and now the location of La Grange Farm and Ranch. Because of its proximity to the railroad, the company was able to handle large amounts of merchandise and became one of the most successful wholesale grocery distributors in the area with branches in Flatonia, Giddings and Elgin. Harry, Charles and Victor were traveling salesmen, Jake was the manager, and Rae served as the bookkeeper. However, the Great Depression took its toll, so the business closed around 1937.

The matriarch of the family, Dora Alexander, died of hemorrhaging due to an ulcerated stomach at age 77 in 1923. Being a member of one of the most prominent families in town, a city ordinance was passed when she became ill just before her death that her home be designated a “quiet zone” for her rest and recovery. She was buried in the La Grange City Cemetery next to her husband.

Harry Alexander never married and continued to live in the family home until his death in a Houston hospital in 1929 of a kidney disease. Charles married Cora Jacobs of Houston and had one son, Charles S., who became a physician. Charles, Sr. worked with the Alexander Wholesale Grocery for 30 years, eventually as the manager of the Flatonia branch and vice-president of the company. He succumbed to gastrointestinal cancer in 1933.

Miss Essie, as she was known, never married and also remained in the family home. She moved to Houston around 1965, a few years before her death, to live with her sister, Gertrude. Preferring literary activities, Essie was a charter member and president of the Etaerio Club when the women’s literary club donated their library building and books to the city for a public library. She also was a leader in getting the new monument covering the tomb at Monument Hill State Park. She died of old age in April 1968 at age 97.

Henrietta “Hattie” married Benno Hellman and lived in Houston; they had two children: Bertha and Alexander. Hattie died in 1933, the same year as her brother, Charles. Victor Dunn Alexander also remained single, living at home and working for the family business for over 30 years before his death in 1932 of Brill’s Disease, a delayed reaction to a typhus infection.

Jake married Carrie Westheimer, a daughter of M. L. Westheimer of Houston, a German Jew who purchased a 640-acre tract extending from what is now Bellaire Blvd. to beyond present-day Westheimer Road, which was established through his land as a shortcut to Sealy and Columbus. After several business ventures, Westheimer established the Houston Livery Stable. Jake and Carrie had four children: Michael, Carol, Richard and Jacolyn. Carrie, praised for her civic and charitable efforts in the community, died in 1934 at age 53 of post-operative shock. Jake moved to Houston in 1941 and became a life insurance salesman. He died there in 1953 at age 73 of coronary heart disease and was buried beside Carrie in La Grange.

Rae Alexander was briefly married to Harry Paul Limburg; after their divorce, he moved to El Paso and remarried. Rae assumed her maiden name and lived with her single siblings in their family home. She died of a cerebral vascular accident in 1944 in the La Grange Hospital at age 63. Gertrude “Gertie”, who also remained single, enjoyed painting as a pastime like her older sister, Hattie. She eventually moved to West University Place in Houston in the 1960s, where she worked as a secretary and cared for her older sister, Essie. She died there in April 1968 at age 83 of metastatic cancer.

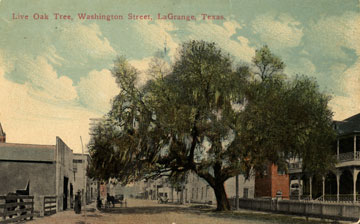

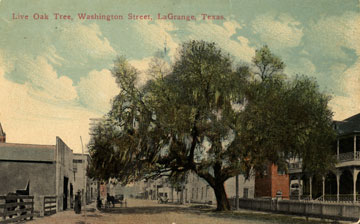

The youngest daughter, Jeannette Cecilia, who never married, was probably the best- remembered of all the Alexanders. She was a well-known piano teacher for almost 50 years, beginning in 1909 when she graduated from college. Her recital program from 1910 shows that Verna Letzerich (Reichert) was one of her pupils. Ironically, years later when a large branch fell off of the large live oak tree in front of the Alexander home onto a parked car, and city officials ordered the tree to be removed, Verna became involved. Upon learning that the city was planning on removing all of the live oaks that were in or very close to the streets, Verna circulated a petition that was signed by hundreds of citizens to stop that effort and save the trees.

Jeanette played the organ or piano for almost every church in town and was the organist at Temple Israel in Schulenburg for years. After the death of Gertrude, Jeannette moved to Houston to care for Essie, who died six months later. Jeannette remained in Houston to be closer to her nieces and nephews and died there in 1977 at age 88 of a heart attack secondary to colon cancer. All of the Alexander children, except Henry, were buried in the La Grange City Cemetery.

It seemed that there was a genetic thread in both the Seelig and Abram Alexander families for gastrointestinal disorders and cancer, as well as cardiovascular diseases.

Because there was no synagogue in La Grange, the Alexanders, who were Reform Jews, traveled to Houston by train to attend services at Temple Israel, especially for High Holy Days. In 1936, a congregation of Jewish people from Fayette, Colorado and Lavaca Counties organized a Tri-County Section with services held in Schulenburg. The Alexanders became active members of this group, helping to contribute to the building of the Temple Israel in Schulenburg in 1951.

The Alexanders were also active in the Masonic Lodge like many Jews in Texas. Abraham, who joined the local lodge in 1864, and all of his sons except Jake were members. Jeannette was the first person in La Grange to join the Eastern Star, a Masonic auxiliary organization.

The Alexanders, who lived in La Grange for over 100 years were very respected and involved members of the community. According to family recollections, they did not suffer any anti-Semitism other than from Dora Alexander’s family. Their beautiful home was eventually sold and razed. The Fayette County Record office now occupies the site of the old Alexander home.

Photo Captions

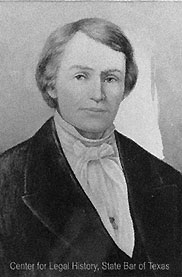

Upper

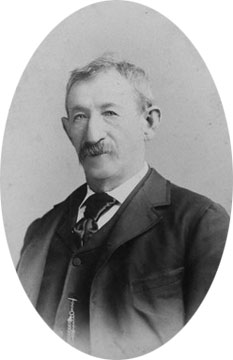

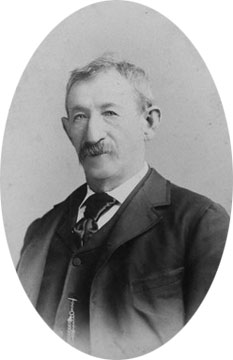

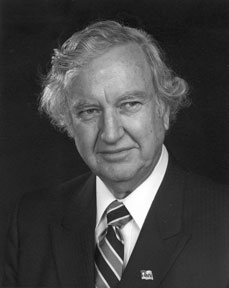

: Abraham Alexander; photo courtesy of Ancestry.com

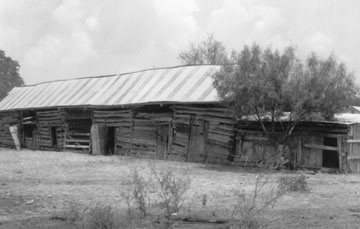

Lower: The Abraham Alexander home on South Washington Street, La Grange; photo courtesy of the Fayette Heritage Museum and Archives

Sources:

Alexander files; Fayette Heritage Museum and Archives

Ancestry.com; immigration, census and death records; family trees

Fayette County Record; May 18, 1876; Vol. 4, Ed. 1

McMillion, Robin. “The Abraham Alexander Family”, Fayette County Past & Present; La Grange, 1976

Obituaries; www.fayettecountyhistory.org

Vogel, Vickie. “House of Alexander”, Texas Jewish Historical Society; November 2011

www.findagrave.com

Taking a Train Ride for Piano Lessons in 1940s

by Gesine (Tschiedel) Koether & Al Cordes

Reminiscing with my dear friend, Al Cordes, about piano lessons brought back memories of a different time. Al’s story provides us with an enchanting memory of a time gone by. Enjoy.

Reminiscing with my dear friend, Al Cordes, about piano lessons brought back memories of a different time. Al’s story provides us with an enchanting memory of a time gone by. Enjoy.

Al writes: “Back in 1946, we would catch the train in Fayetteville and ride it to LaGrange on Saturday morning around 10 o’clock. There were three of us: Rose Marie Baca (11), Jimmy Sarrazin (12) and myself (13). We would go into the Depot and Mr. Danchek, the depot agent, would sell us tickets. As I recall, Rose paid only 20 cents for the one way ten mile trip (her dad picked her up after her lessons in LaGrange). Jimmy and I paid 35 cents for a round trip ride. It was exciting; the steam powered train came in with a lot of noise and shook the ground. We boarded a nearly empty passenger car and were given an air conditioned ride straight through the woods past the ‘Blue Hole’ near Halsted. It looked like a morning glory full of clear water about 80 feet across. It only took about 20 minutes to get to the depot in LaGrange. We would get off and walk past the Cozy Jr. Theater, the Corner Drug store and fountain and then across the square in front of Perry’s 5 and 10. Finally we would cross Hwy 71 to get to the Alexander home behind the old St. Paul’s Lutheran Church (not the present church location).

"The Alexander home was a classic Southern mansion, a full 2-1/2 story wooden structure that had not changed from the 1920’s. We were received by Miss Essie, our piano teacher’s sister, and ushered into the study. The study is where she entertained us as we were waiting our turn for lessons from Miss Jeanette Alexander. Miss Essie had us listen to the Texas Star Theater of classical music on her radio while we waited.

"Miss Essie and Miss Jeanette were delightful women and full of grace and goodwill. They were very proud of their grandfather who had a factory that made hats for the Confederacy during the Civil War. The house had many oil paintings hanging on the walls that had been painted by family members over the years. It is truly a shame that this house was destroyed to make way for a brick office building (The Fayette County Record office).

"Miss Jeanette was a graduate of the Julliard School of Music in New York. She had a Steinway Grand piano and she complained to me one day that she was afraid the Schwartz boy would wreck her piano because he hit the keys so hard. The irony here is that he went on to become a concert pianist!

"Rose’s father normally picked her up and took her home. When Jimmy and I finished our music lessons, we would go to the Corner Drug Store for a treat. My favorite was a Black Cow (root beer with a scoop of Polar Bear vanilla) and it cost only a dime. Then if the train was a little late we would go to the Cozy Jr. for a Grade B Western (Lash LaRue, Tom Mix….)

"As the Cozy owner became aware we were just killing time until our train ride back to Fayetteville, he would sometimes let us come in for free. Sometimes we would have to sprint from the show to the train as we had cut it too close and the train’s whistle could be heard.

"We never missed a train, but we had to hustle a few times to keep from getting left behind.”

Thank you so much to Al for sharing his memory with me. He is working on another memory as you read this.

Photo caption: Warren O. Albrecht's photograph of Miss Jeanette Alexander and another sudent in the late 1960s, courtesy of the Fayette Heritage Museum and Archives [1997.40.3]

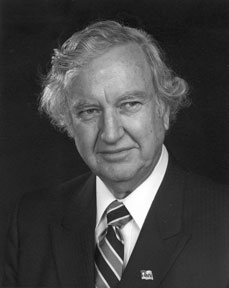

William A. Anders — Apollo Astronaut Who Once Lived in La Grange

by Carolyn Heinsohn

La Grange has the distinction of being the home of one of the Apollo astronauts for several years. Air Force Captain William Alison (Bill) Anders, the son of Cdr. and Mrs. Arthur F. (Tex) Anders (USN Retired) and nephew of E.F. (Smiles) Anders of La Grange, was one of three astronauts who were the first to circle the moon on Christmas Eve, 1968.

La Grange has the distinction of being the home of one of the Apollo astronauts for several years. Air Force Captain William Alison (Bill) Anders, the son of Cdr. and Mrs. Arthur F. (Tex) Anders (USN Retired) and nephew of E.F. (Smiles) Anders of La Grange, was one of three astronauts who were the first to circle the moon on Christmas Eve, 1968.

Anders was born in Hong Kong on October 17, 1933 while his father was stationed in the Far East. After his father’s retirement from the military, the family moved to La Grange, where they lived from 1946 to 1950. The two Anders brothers, Arthur and E.F., bought the Hermes Drug Store and operated it as a partnership.

It was during this time that Bill Anders attended the local public schools, beginning in the eighth grade and continuing through his junior year of high school. He always remembered his academic training in La Grange, having written his uncle several times about how he valued his schooling here and especially singled out Superintendent Charles A. Lemmons for his counsel and guidance.

The Anders family returned to California where Anders graduated from Grossmont High School in La Mesa in 1951. He received a Bachelor of Science degree in Electrical Engineering from the United States Naval Academy in 1955. Following his graduation, Anders took his commission with the U.S. Air Force and received his pilot wings in 1956. He served as a fighter pilot for the Air Defense Command in California and Iceland, logging more than 8,000 hours of flight time. He also earned a Master of Science degree in Nuclear Engineering from the U.S. Air Force Institute of Technology at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio, in 1962.

In 1963, Anders was selected by NASA in the third group of astronauts and was the backup pilot for the Gemini 11 mission. In 1968, he was chosen to accompany Frank Borman and James A. Lovell, Jr. for the Apollo 8 mission, the first mission where humans traveled beyond Low Earth orbit. This historic manned space flight orbited the moon for ten revolutions. Anders also served as the backup Command Module pilot for the Apollo 11 mission, before accepting an assignment as Executive Secretary for the National Aeronautics and Space Council from 1969 to 1973.

On April 19, 1969, La Grange honored one of its own with “Bill Anders Day”. Anders and his family attended the event, which included a parade, reception, barbecue and a program of film and slides on his space flight.

In 1973, Anders was appointed to the five-member Atomic Energy Commission and was also named as U.S. Chairman of the joint U.S./USSR technology exchange program for fission and fusion power. President Ford then named Anders to become the first chairman of the newly established Nuclear Regulatory Commission, which was followed by an appointment to serve as Ambassador to Norway until 1977. At that time, he ended his career with the federal government after 26 years and began work in the private sector. He joined the General Electric Company as general manager and became a senior executive of its nuclear energy products and aircraft equipment divisions. He later joined Textron Inc. in Rhode Island as its senior executive vice president for operations, a position he held for five years.

In 1990, Anders became the chairman and CEO of General Dynamics, a large military supplier and parent company of Electric Boat, that employed over 100,000 people at the time. He retired in 1993, but continued to serve as president of the William A. Anders Foundation, a philanthropic organization dedicated to supporting educational and environmental issues. He received a number of awards and honors, including being inducted into the International Space Hall of Fame and having a crater on the moon named after him.

Anders married Valerie Hoard in 1955; they have four sons and two daughters and presently live in Washington State. He has a legacy of notable achievements and took part in the making of history during our time. We are definitely proud that he called La Grange home for a short while!

Photo caption: William A. Anders, courtesy of Wikipedia.org (Public Domain)

Sources:

Meiners, Carolyn. “Anders, William A.”, Fayette County, Texas Heritage, Vol II; Curtis Media, 1996

“William Anders”; Wikipedia.org

Texas Governor From La Grange?

by Katie Kulhanek

Born in La Grange on January 18th, 1848, Reddin Andrews’ life was destined to be one of excitement. His profession carried the terms of soldier, college valedictorian, preacher, college professor, newspaper editor, Texas gubernatorial candidate, and even author. Four years after Reddin was born, his mother, Mary Jane (Talbert) Andrews, passed away. The young Andrews then lived in the home of J.L. Gay – his brother-in-law. When war broke out between the North and South, Andrews enlisted in the Confederate Army as a scout and courier. He enlisted in the year 1863 when he was only 16 years of age. Once the war had ended, Andrews returned to Fayette County and continued his schooling, eventually joining the Shiloh Baptist Church. He later enrolled in Baylor University and graduated as valedictorian of his class in 1871. He proceeded to join the Baylor University faculty and teach primary classes in exchange for the tuition costs accumulated over the past years. Not long after, he became ordained as a Baptist minister and left Texas to study at Greenville Seminary in South Carolina. He returned to Navasota in 1873 where he worked with churches in Millican, Hempstead, Calvert, Tyler, Rockwall, and Lovelady. By August of 1874 Reddin was married to Elizabeth Eddins, with whom he had 9 children – 2 died young. Andrews continued his teaching at Baylor University, becoming a professor of Greek and English literature. Due to financial troubles, however, he resigned in 1878 and became principal of the Masonic Institute at Round Rock. By 1881, Andrews had accepted the pulpit in Tyler where he became the contributing editor to John B. Link’s Texas Baptist Herald - a newspaper out of Houston that was published from 1865 to 1886. In Tyler, he had a “filial relationship” with the president of Baylor, William C. Crane. Crane was like a father to Andrews. After Crane’s passing, Andrews became the president of Baylor, and was also the first Texas-born president of Baylor University. In 1885, under Andrews’ presidency, Baylor University was moved to Waco and merged with Waco University – where it currently is today. A year later, Andrews became a member of the committee that merged the Baptist State Convention and the Baptist General Association – thus creating the Baptist General Convention of Texas.

In 1889, Andrews decided to move to Atlanta, Georgia and work on editing W.T. Martin’s Gospel Standard and Expositer. He returned to Texas a year later, and quickly became an expert on the problems of rural congregations due to his work with Martin’s text. Andrews moved to Belton in 1892 to teach and become an organizer for the People’s Party or Populist Party. He was mentioned to run for a state office, but was never nominated. During these years, he worked both as a minister and politician. Andrews was involved in radical politics, believing that if one believed in Christianity, then they also must pledge an allegiance to socialism. He believed that the “ethics of Christianity and socialism were identical” to one another. It was during this time that Andrews also became editor for the Sword and Shield in Tyler, Texas.

As a socialist candidate, Andrews ran for governor of Texas in 1910. He came in 3rd in the race with 11,538 votes, behind Democrat Oscar Branch Colquitt (174,596) and Republican J.O. Terrell (25,191). Andrews did come in ahead of the Prohibitionist candidate, Andrew Jackson Houston, who gathered 6,052 votes. In 1911, Andrews took a break from politics and started working on a book composed of his own original poems taken from his sermons and other occasions. The collection was published and titled Poems. In 1912, Andrews entered back into politics and tried again to beat out the incumbent (Colquitt). This time, Andrews came in 2nd with 25,258 votes. Colquitt was re-elected and continued to serve as governor of Texas until 1915. Considering that Andrews was a socialist, it is interesting that he was able to come in 2nd overall in the 1912 gubernatorial race. But it is worthy to note that the numbers in his county of birth, Fayette County, were not as impressive. In the 1912 election, 2,709 votes were cast – but only 96 of those went in favor of Andrews – only 3.5%. In 1916, Andrews moved to Lawton, Oklahoma and lived there until his death on August 16, 1923, he was 75 years of age. He was one of the most prominent Texas Baptists of our time.

Early Archeology in Fayette County

by Gary E. McKee

History is the term applied to events occurring after written records have been kept. In Texian terms, history began with Cabeza de Vaca publishing a journal of his visit to the Texas coast beginning in 1527. All events happening before this time is referred to as prehistory. Archeology is the reconstruction of history prior to written records. For milleniums the area bordering the Colorado River has been a cultural oasis. Traces of early human culture have been identified at numerous locations.

In 1966, work was underway at the Frisch Auf! golf course when workers digging a trench unearthed skeletal remains. The owners contacted the State Archeologist, who soon arrived with a small crew to investigate and perform salvage archeology. Excavations were begun and the ground yielded parts of at least four skeletons, fragments of a fifth, and quite possibly a sixth. The bones were at a depth from 16 to 30 inches. Placement of the remains indicates that burial times differed.

The skeletons were removed from the pipeline trench to be studied. Analyses of the first pair of skeletons show them to be adult males. During excavation, two Scallorn arrowpoints were found lying between the males. The presence of these flint projectile points suggests that these two humans were interred between A.D.700 and A.D.1200.

The third proved to be a child, possibly a male lying, on its side.

The fourth was an infant. Accompanying the infant were three offerings for the next world. On the west side of the skeleton was an antler tine that was oriented in a north south direction. North of the skeleton and lying east-west lay a piece of petrified wood that had been shaped and smoothed. Adjacent to the smoothed stone lay one valve of a fresh water muscle with its concave surface up.

The other two skeletons appeared to be an infant and possibly an adult male. The construction equipment had rendered further identification impossible.

A surface survey was conducted turning up a shard of Leon Plain pottery. The reddish exterior and dark brown interior had been tempered with pulverized bone and grit. This type of pottery has been associated with a culture later than the Scallorn points. Several flint tools were also recovered.

The significance of the discovery is that this is the first Scallorn point found in a Central Texas burial, which greatly aids in identifying the age of the skeletons.

The Arnim Brothers

by Donna Green

In March of 1886 in the small frontier Texas town of Tascosa a huge gunfight took place. Bodies of the dead and wounded were lying all over the main street of town as residents came out to gawk after the shootout was over. One of the badly wounded men in the street was Charley Emory. His brother, Tom, had also been involved in the fracas but was uninjured.

What does this have to do with the history of Fayette County? The Emory brothers were not really named Emory. Charley and Tom were brothers but their surname was Arnim.

Tom had been born William Arnim. His parents were Alexander and Marie Arnim who owned a grocery store in Fayette County. William had been convicted at age twenty-two in Fayette County district court of theft of an ox and sentenced to two years in prison. William arrived at Huntsville on June 9, 1876 and was entered into the prison record as prisoner # 5339. He was described as having red hair, blue eyes, and being a slender young man. William escaped from custody on March 21, 1877 and headed west. He changed his name to Tom Emory and settled near Tascosa. His younger brother, Charley Arnim, joined him some time later and also adopted the Emory surname. Tom and Charley worked on ranches in the area, played poker in the saloons and sometimes worked as deputies with Pat Garrett. While working as deputies they once pursued Billy the Kid all the way to Nevada but then lost his trail.

In May 1896 a petition was sent to Governor C. A. Culberson for a pardon for William/Tom. Testimonials and affidavits backed the petition from both the county attorney who had prosecuted William/Tom and the judge who had sentenced him. Judge L. W. Moore wrote "The reputation of the convict since his escape from the penitentiary has been good. There is no family more esteemed than of this man and he is represented by those who know him as reformed and making a good citizen." Shortly afterwards, William/Tom surrendered himself to prison authorities at Huntsville on May 9 and his pardon was granted on June 16.

Released to the Schulenburg community, he lived a blameless life thereafter. He died on May 26, 1914 and is buried in Schulenburg. Charley died March 9, 1895 and is buried near Flatonia.

Compulsory Auto Insurance

By Marie Watts

By the late 1920s, automobile accidents were a routine occurrence in Fayette County. The La Grange Journal reported on November 29, 1928 that John Korenek Jr. was injured when a Ford he was driving was hit by a Ford roadster occupied by two men employed by the pipeline company west of La Grange. The other driver, L. A. van Brant, was taken into custody and charged with operating a motor vehicle while intoxicated.

By the late 1920s, automobile accidents were a routine occurrence in Fayette County. The La Grange Journal reported on November 29, 1928 that John Korenek Jr. was injured when a Ford he was driving was hit by a Ford roadster occupied by two men employed by the pipeline company west of La Grange. The other driver, L. A. van Brant, was taken into custody and charged with operating a motor vehicle while intoxicated.

Five days later, the Journal reported that Taylor Cage of Bishop was discharged from the La Grange Hospital after being treated for several days for injuries sustained when the auto in which he and G. W. Nanney were riding hit a freight car standing on the tracks between the two cemeteries east of La Grange.

But, who was to pay? The driver who was responsible, of course. But what if he could not pay?

Connecticut took the first step to resolve this problem in 1925 by offering insurance and requiring drivers to demonstrate they had the means to take financial responsibility for injuries, deaths, or property damage. By 1927, the 40th Texas State Legislature had followed suit by creating the Board of Insurance Commissioners, composed of the life insurance commissioner, the fire insurance commissioner, and the casualty insurance commissioner. The legislature granted the insurance commissioner the power to approve or disapprove auto insurance rates and to promulgate uniform policy forms. However, Massachusetts went one step further that year, making auto insurance mandatory.

Mandatory auto insurance was a tough sell in Texas as well as in the rest of the nation, however. The Flatonia Argus ran an editorial in 1925 disparaging required coverage. The editor feared the state would expand into the field of private business under the guise of preventing accidents. The state might establish state-run auto insurance or set up state automobile funds, collecting and expanding the funds as it had recently done with workers’ compensation.

Mandatory insurance, the writer warned, would open itself to fraud and carelessness. Poor drivers would no longer be held in check by fear of personal liability and responsibility; they would simply say “let the insurance company pay”. Then, too, compulsory insurance would force good drivers to pay higher rates than poor risks who required insurance.

The La Grange Journal reprinted a 1928 article from the Hartford (Connecticut) Courant discussing what was happening in Massachusetts and why mandatory insurance would not work. First off, Massachusetts had difficulty making their program run smoothly and satisfactorily. The state had set rates that were too low to induce private companies to write policies and then, when the legislature tried to raise rates, the citizens balked. The writer then commented, “…it has proved extremely difficult to keep politics out of the question. The opportunity for politicians to make capitol of an issue on which public feeling is strong is too great to be resisted”. The primary objection was that, the longer the program continued, the more it appeared to be pushing the state government into the insurance business.

Insurance Commissioner Dunham of Connecticut was quoted as saying, “I regard it as fortunate that this experiment has been carried on in Massachusetts, for if it has not worked there, how will compulsory automobile insurance be expected to work well anywhere else?”

It was not until 1991 that Texas mandated compulsory auto liability insurance. Today, New Hampshire, the “Live Free or Die” state is the only one that still allows drivers the choice to drive uninsured. The only requirement is that drivers demonstrate that they can provide sufficient funds in the event of an “at-fault” accident.

Photo caption: East side of La Grange square with Ford Model Ts parked and participating in a parade; circa 1920; photo courtesy of Fayette Heritage Museum and Archives

Sources:

“Background on: Compulsory Auto/Uninsured Motorists” downloaded from https://www.iii.org/article/background-on-compulsory-auto-uninsured-motorists on April 7, 2018.

“History of the Texas Department of Insurance” downloaded from http://www.tdi.texas.gov/general/history2.html on April 7, 2017.

The Flatonia Argus; January 29, 1925.

The La Grange Journal; November 29, 1928, December 4, 1928, and December 6, 1928.

“When Did Auto Insurance Become Mandatory?” Downloaded from https://www.autoinsurance.org/when-did-auto-insurance-become-mandatory/ on April 6, 2018.

The Baca Family Band

by Helen Mikus & Linda Dennis

The Beginning – Joseph, Frank J. and the original members

In 1860, Joseph Baca came to Fayetteville, Texas from Bordovice, Moravia which was part of the Austrian/Hungarian Empire. The name Baca in English means shepherd and is pronounced with a soft “c” (Ba-cha). The name Baca for more than a century has been a part of Texas history along with the famous “Baca Beat.”

In 1860, Joseph Baca came to Fayetteville, Texas from Bordovice, Moravia which was part of the Austrian/Hungarian Empire. The name Baca in English means shepherd and is pronounced with a soft “c” (Ba-cha). The name Baca for more than a century has been a part of Texas history along with the famous “Baca Beat.”

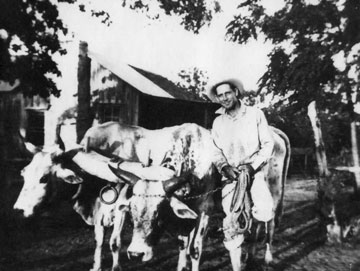

Joseph took on the difficult and dangerous job of hauling cotton to Mexico in a wagon drawn by six to twelve oxen. After the Civil War, he returned to the farm which was four miles east of Fayetteville. Joseph and his two sons, Frank J. and John, helped their neighbors build a school for the community. Since many had come from around the same area in Moravia, they named the school Bordovice. Joseph was not musically inclined and never played in any of the Baca bands. His offspring and their children were born entertainers!

By the age of nine Frank J. exhibited a remarkable musical talent. He taught himself to play the clarinet. When Frank J. had the chance to study music, he wrote and composed music of his own. He arranged and composed music with organ rollers and played the alto and slide trombone.

Frank J. Baca married Marie Kovar who came to Texas with her family from Hovezi, Moravia. He composed music for the first Czech Orchestra organized in Fayetteville. He became known as Professor Frank J. Baca, leading the Baca Family Orchestra which eventually consisted of all thirteen of his children playing various instruments. This was the beginning of the famous “Baca Beat.”

Baca Bands have played for the Annual Tomato Festival, at Monument Hill, La Grange, San Jacinto Battle Grounds & Fairs, and numerous Fayetteville occasions. For many years on Corpus Christi (Body of Christ) Day in Fayetteville, the priest would go around the town square and stop at each corner to hold a service. Later the ceremony was moved to the parking lot of St. John the Baptist Catholic Church where it is still held today.

Throughout the years many of the original members have been replaced. The following were the original thirteen children of the Baca Family Band and Orchestra along with their birth year: Jennie Baca Scherpik 1882, Joe O. Baca 1883, Mary Baca Kubena 1885, Frances Baca Zapalac 1886, Frank A. Baca 1887, Anna Baca Stastny 1889, Rudolph Baca 1890, John R. Baca 1892, Raymond Baca 1893, Emilie Baca Kulhanek 1895, Julia Baca Chalupa 1896, Ludwig Baca 1898, and Betty Baca Tschiedel 1899.

Frank J. Baca planned to make a national tour with the band but died of a rare disease at the age of 46. His oldest son, Joe O. Baca, then took over the band. He was also a natural musician and began to play at an early age. He won first place in a La Grange music contest at the age of twelve playing the cornet. He went on to win many music awards as an individual and with the Baca Family Band. In the early 1900’s, the band competed in a La Grange competition where each band was given a piece of music that they had never seen before. They were judged on how well they performed without practice. The Baca Family Band was the first place winner.

The dulcimer was used a great deal in the early days of the Baca Band. Joe Baca’s uncle, Ignac Krenek, made his first dulcimer in 1892 and later gave it to Joe. There were only a handful of dulcimers in the entire state of Texas. In Czech the dulcimer is called a cimbal. It is triangular in shape, consists of 120 strings and is played with two wooden mallets. Ignac’s dulcimer weighed 86 pounds. The instrument dates back hundreds of years before Christ and is shown in drawings from Assyrian Kings in Babylonia. If you have never seen a dulcimer or want to know more about the Baca Band visit the Fayetteville Area Museum.

Bands, Records, Celebrations, Orchestras

In 1912 the Baca Band and Orchestra was honored by the grandson of the famous Czech Composer Antonin Dvorak. While visiting Texas, he stopped in Fayetteville and played with the band under the leadership of Joe Baca.

When WWI soldiers returned home to Fayetteville, they were treated with the respect they well deserved. Uniformed solders were led by the Baca Band as they marched around the town of Fayetteville and to the SPJST Hall.

In 1920, Joe O. Baca died at the early age of 37. Everyone thought that would surely be the end of the band but thankfully, it was not. John R. Baca stepped up to the plate and became the bands new leader.

The Band played for the first time for Houston’s KPRC Radio Station in 1926 and 1927. With the recordings of the John R. Baca Orchestra made for the OKEH Phonograph, in 1931 for Columbia and 1935 for the Brunswick Corporation, he became known as the “Polka King of Texas.”

Baca's Brass Band, ca 1932

at the Fayetteville Precinct Courthouse Square Band Stage

Edward "Eddie" Baca, Frank A. Baca, Jr., Ludwig B. Baca, John R. Baca (Director), Raymond "Ray" Baca Sr., V. Kulhanek, Anton Kulhanek, Frank Gerik, Rudolph A. Baca, Frank Kulhanek, Lad Baca, Leonard Baca

|

The John R. Baca Band celebrated their 40th Anniversary in the summer of 1932 in Fayetteville Included with the twelve members of that day, three were members of the original Baca Band . They were: Joseph Janak of West, John Kovar of Fayetteville and Frank J. Morave of Robstown. A large parade was held with four other bands attending. The Baca Band led the way to the SPJST Hall where all parades concluded. The Baca Band also played at St. John the Baptist Catholic Church service that day. A feast of around 2,000 pounds of barbecue and tons of stew were served. Baseball games were played in the evening and music was played all day.

In 1932 the Fayetteville Courthouse Square Bandstand was built. The Baca Band gave Sunday concerts there for many years to the delight of townspeople and visitors.

The John R. Baca Band participated in the 1936 Centennial Celebration. The youngest member was John’s son Clarence who was playing the drums at age sixteen. In later years, Clarence and two others organized the SPJST Lodge #88 Concert Band. In 1962 he organized the Clarence Baca Band and played until 1998. They played at places like the Rice Hotel, Shamrock Hotel, Bill Mraz Dance Hall, SPJST Lodge #88, all in Houston, and the Buccaneer Hotel in Galveston while they were making records.

In around 1933, Raymond “Ray” Baca, Leonard Baca, Frank A. Baca, Jr., and Frank Kulhanek organized a band of their own with Ray as the leader. They named it “Baca’s New Deal Orchestra”. That year, the band won first place for their arrangement of “Rancho Grande” at the Yoakum’s Tom Tom Festival.

In 1937, John R.’s brother Ludwig “L.B.” Baca left John R. Baca’s band. He moved to Rowena and took charge of the Ripple Orchestra and renamed it the Baca-Ripple Orchestra. In 1938 he changed the name to the L.B. Baca Orchestra.

Ladislav “Lad” Baca was the son of Joe O. Baca and Louisa Krenek Baca. He was taught to play the drums at the age of nine by his father. He soon learned to play seven instruments and had the ability to play any new instrument within five minutes of picking it up. At the request of Elo Rohde, the Fayetteville High School Superintendent, he taught the first Fayetteville High School Band. A deal was made with the school that his parents, not the school, would pay him.

The divided orchestras now consisted of John R. Baca’s Orchestra, Ray Baca’s New Deal Orchestra (later changed to Ray Baca’s Orchestra), and the L.B. Baca Orchestra. They all had that famous and very popular “Baca Beat.”

And the “Baca” Beat Goes On

Anna Baca, daughter of Frank J. Baca Sr., started the Anna Baca Stastny Family Band. This band consisted of her husband, Frank Stastny Sr. (bass), Frank Stastny Jr. (clarinet), Edwin (trumpet), Johnny (dulcimer) and Anna (drums). The sons were very young when they started playing. During the depression years they played for free on many occasions. People needed cheering up and didn’t have the money for entertainment. When WWII began, the band broke up and never played together again. Anna lived to the amazing age of 100. Frank Stastny, Jr. is still in Fayetteville and sings with his church choir.

In 1953, at the age of 60, John R. Baca, director of the Baca’s Original Band and Orchestra for 33 years, passed away. He was granted his desire to be buried in his band uniform. The town of Fayetteville honored him by closing all businesses during his services. The town marched from the funeral home, through town, to the church and to the cemetery led by the music created by the Bacas.

After John R. Baca’s death, his children Lee Edward Baca, Clarence Baca and Rosemarie Baca Rohde kept the band going along with the help of Joe Baca’s son Eddie.

Next we see Ray Baca who started his musical career at the age of eight. He played with his Father Frank J. Baca’s Family Orchestra. In 1970 his band consisted of Emil V. Baca (sax & clarinet), Henry Hrachovy (accordian & trumpet), Emil Hrachovy (guitar), Donald Cernosek (trumpet), Norman Barnes (bass) and John Sumbera (drums).

Ray’s two sons were extremely talented and followed the family tradition. Gil began playing the piano at the age of fourteen and Kermit was nine when he started playing the drums. In 1949 Gil and Kermit went on tour with Tennessee Ernie Ford and then went on to join Hank Thompson’s group that toured the USA and Canada. In 1952 Kermit was drafted into the U.S. Army where he formed his own band while stationed in Alaska for two years. Gil appeared on the Kate Smith Show and other top TV shows. Later Gil and Kermit formed their own band. The played at various Houston clubs and made appearances on Channels 11 and 13. Initially, they played popular tunes but that changed when Ray Baca joined them. They added polkas and waltzes to their repitoirre. They recorded the famous Baca Waltz and Gil’s Polka. In 1967, they cut an LP featuring Ray Baca on the dulcimer.

The Smithsonian Institute in Washington D.C. invited Ray with Gil & Kermit’s Band to take part in the American Folklife 2nd Festival July 1-4, 1967. The Band left Houston International Airport with a big send off from SPJST #88 which was televised on Channels 2 and 11. As the 100 year dulcimer was so valuable, the Smithsonian purchased a ticket for it to ride in its own seat! To the enjoyment of all of the passengers, Ray Baca played his beloved dulcimer 33,000 feet in the air. The “Baca Beat” was so well received that they were invited to perform again in 1968 and many more times including one of President Richard Nixon’s Inauguration Balls. The Baca Orchestra was chosen for the Folklife Festivals for its ability to present the American survival of the Czech folk tradition in its most happy and authentic form. The Baca Band was again featured in this festival for the bicentennial year of 1976. in 1972, for the 80th Anniversary of the beginning of the Baca Bands, Gil Baca’s band featuring Ray Baca, returned to the home of their ancestors for a two week tour.

The Smithsonian Institute in Washington D.C. invited Ray with Gil & Kermit’s Band to take part in the American Folklife 2nd Festival July 1-4, 1967. The Band left Houston International Airport with a big send off from SPJST #88 which was televised on Channels 2 and 11. As the 100 year dulcimer was so valuable, the Smithsonian purchased a ticket for it to ride in its own seat! To the enjoyment of all of the passengers, Ray Baca played his beloved dulcimer 33,000 feet in the air. The “Baca Beat” was so well received that they were invited to perform again in 1968 and many more times including one of President Richard Nixon’s Inauguration Balls. The Baca Orchestra was chosen for the Folklife Festivals for its ability to present the American survival of the Czech folk tradition in its most happy and authentic form. The Baca Band was again featured in this festival for the bicentennial year of 1976. in 1972, for the 80th Anniversary of the beginning of the Baca Bands, Gil Baca’s band featuring Ray Baca, returned to the home of their ancestors for a two week tour.

For a number of years, Gil Baca and Lee Edward Baca, Vernon Drozd and Alvin Minarcik along with various guest performers played at the historic Baca’s Confectionary in beautiful historic downtown Fayetteville. Rudolph Baca, proprietor, was a former John R. Baca Band member for 33 years. He played the tuba, bass and violin. Around 2005, the building was sold and can now be visited as Joes’ Place which is a restaurant.

Gil Baca’s final public performance was at the dedication of the City of Fayetteville to the National Register of Historic Places on September 8, 2008. If you did not know it, Gil was critically ill as he gave the performance of a lifetime. He played his keyboard smiling and singing as Czech dancers swirled across the stage. Soon after that beautiful performance, Gil was lost to us but the Baca Beat will live in our hearts forever.

We now await the next Baca to please step forward . . .

Sources:

Interviews with Gil & Flo Baca, Rosemarie Baca Rohde, Frank Stastny, Jr.

Baca Record Covers

Baca Musical History from 1860-1968 by Cleo R. Baca

Photos from Fayetteville Area Heritage Museum

An Early Fayette County Band

By Judy Matejowsky

Remembered by descendants of each entertainer, but obscure to others by now, I’d like to tell you about a group of friends who formed a band in the Nechanitz area in the 1920s.

Remembered by descendants of each entertainer, but obscure to others by now, I’d like to tell you about a group of friends who formed a band in the Nechanitz area in the 1920s.

Ninety-plus years ago, Edgar Edwin Frenzel, who played the saxophone, formed the ensemble. The other musicians, all in their 20s and 30s with differing talents, were: Ernst/Ernest Luecke (dulcimer), August Meinke (trumpet), Emil Albers (saxophone), Eddie Albers (clarinet), Gus Weber (violin) and three Matejowsky brothers, Anton (trombone), Alois (trumpet), and Elmo (drums). There could have been two to three others whose names are unknown to me. They collectively named themselves The Lion Tamers Band and Orchestra, sometimes adding the word “Brass” before “Band”.Fascination still exists about their puzzling name.

Automobiles were the mode of travel in the mid-to-late 1920s when the band was active. Gigs were booked in the accessible neighboring towns and communities of Winchester, Indian Creek, Waldeck, Warrenton, Dime Box, Oldenburg, Giddings, Ganttsville (now Prospect in Lee County) and even as far as Brenham. Events included weddings, feasts, community celebrations and school sponsored dances. These young men worked hard every day, but loved music enough to practice regularly and perform when requested.

The first commercially licensed radio broadcast in the United States went out in 1920. By 1922, there were 600 radio stations in the country. Families began purchasing radios, and there was an eager audience for listening to music. Change was in the air!

The 19th Amendment had given women the right to vote, but liberation did not stop there. The 20s was the age of the “flapper”, a time when women, who sought excitement, bobbed their hair and wore their skirts shorter. Songs reflected their behaviors and fashion. Perhaps a love for additional new songs and dancing helped the promotion of bands such as The Lion Tamers.

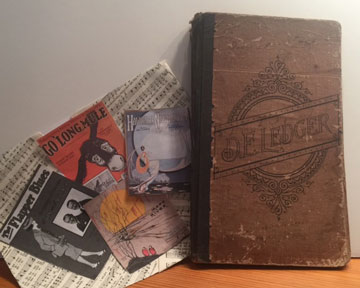

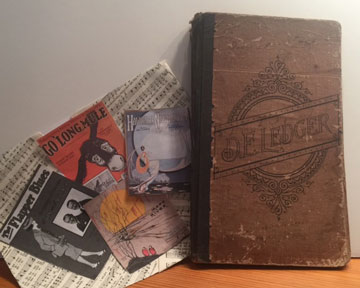

A brown-colored Sterling “D.E.Ledger” (12 x 7 inch, double-entry) owned by Charles and Anton G. Matejowsky has survived. Individual purchase prices for these ledgers were from 25 to 50 cents. Their covers are very beautiful, now even highly collectible.

Over 130 different titles of sheet music, neatly written with black ink, provide a wonderful time capsule of the roaring twenties. Some delightful “oldies but goodies” in that ledger include “Blue Eyed Sally”; “Go Long Mule” (a novelty song, the cover of which says ‘the Dawgonedest Fool Song Ever’); “Wa Wa Waddle Walk”; “Red Hot Mama”; “Sweet Little You”; “West Texas Blues” (a fox trot); “Wabash Blues”; “Moon River” (a beautiful waltz),;“Flapper Blues” and “Hawaiian Nightingale”. One in particular, a waltz, “Let Me Call You Sweetheart”, was immensely popular.

An interesting side note is that Edgar Frenzel (mentioned above) married Miss Lillie Weber, who lived with the three Matejowsky band members’ family for a while prior to her marriage. Lillie had run away from home due to her parents’ disapproval of her choice of a suitor. However, the couple began a long, married life in 1919.

Band member Anton Matejowsky was the father of my husband, Lloyd. Anton’s trombone, minus the mouthpiece, is a much-loved artifact still in our possession. We are hopeful that someday advertising fliers and/or news clippings and pictures of The Lion Tamers Band and Orchestra will surface. If there are any descendants of the band members who still have any of these items, please contact us at czechinn@hotmail.com.

Photo Caption:

Surviving double-entry ledger book and sheet music of the 1920s - 1930s era that were originally owned by Charles and Anton G. Matejowsky; photo courtesy of Judy Matejowsky

Sources:

1920 –1930 Ledger Book belonging to Charles and Anton G. Matejowsky

Interview with Lorena Matejowsky Hannes; Giddings, Texas (sister to the three Matejowsky band members), 1980s

What Links St. Peter’s Lutheran to Bethlehem Lutheran

Carl Siegismund Bauer

by Gesine (Tschiedel) Koether

Growing up in Spring Branch, a suburb of Houston, I went to Spring Branch Elementary School and played right next door to St. Peter’s Evangelical Lutheran Church every school day. It was an old church with narrow windows, a tall steeple and was painted white. We were active members at Holy Cross Lutheran only a few miles away, so only visited St. Peter’s when they held their open house at Christmas. So as a kid, I did not think about St. Peter’s other than to think it was a pretty church, and they had a beautiful Christmas program.

As a member and tour guide for Round Top’s Bethlehem Lutheran, the connection between the St. Peter’s and Bethlehem churches were brought to my attention by Judy Matejowsky. She lent me her copy of the Bauer family book, “A Goodly Heritage”. It tells the story of Carl Siegismund Bauer and his descendants. It surprised me to learn that Bethlehem Lutheran was not the first church that Bauer had built. Ten plus years earlier, Bauer had participated in the building of St. Peter’s in Spring Branch. My elementary school memories now beckoned me to find out more.

Carl Bauer, his wife, Christiana Malzar Bauer, and four of their children, who lived in Saxony, Prussia (Germany), boarded the sailing ship Neptune in 1848 in search of a less turbulent place to live. Carl and Christina were in their mid-fifties when they set off on this journey. August, their second oldest, and his wife Emilie (Ficke) had emigrated in 1847 and sent back encouraging word of all that was available in Texas. The hurricane encountered on their journey, the scurvy-like disease that caused deaths on board the Neptune and the trip inland after arriving in Galveston all proved to be exhausting and dangerous. By 1849 they had made it across the mud flats and swamp-like land to a place approximately ten miles northwest of Houston that other families had named Spring Branch Creek. The Bauers, along with the other German families, including the Rummels, Kolbes, Ahrenbecks, Schroeders and Hillendahls, held a Thanksgiving service for their safe arrival in the wilds of Texas. St. Peter’s Evangelical congregation had begun their plans. The oaks and giant pines were perfect for both their home and a church. William Rummel, who married Caroline Bauer, donated the land and cemetery for the building of St. Peter’s.

Carl Bauer, his wife, Christiana Malzar Bauer, and four of their children, who lived in Saxony, Prussia (Germany), boarded the sailing ship Neptune in 1848 in search of a less turbulent place to live. Carl and Christina were in their mid-fifties when they set off on this journey. August, their second oldest, and his wife Emilie (Ficke) had emigrated in 1847 and sent back encouraging word of all that was available in Texas. The hurricane encountered on their journey, the scurvy-like disease that caused deaths on board the Neptune and the trip inland after arriving in Galveston all proved to be exhausting and dangerous. By 1849 they had made it across the mud flats and swamp-like land to a place approximately ten miles northwest of Houston that other families had named Spring Branch Creek. The Bauers, along with the other German families, including the Rummels, Kolbes, Ahrenbecks, Schroeders and Hillendahls, held a Thanksgiving service for their safe arrival in the wilds of Texas. St. Peter’s Evangelical congregation had begun their plans. The oaks and giant pines were perfect for both their home and a church. William Rummel, who married Caroline Bauer, donated the land and cemetery for the building of St. Peter’s.

After the Christmas holidays of 1849, the men of those founding families went into the woods, cut logs and left them to season. These first logs were gone when they returned later to retrieve them. The next cut logs were kept under the watchful eye of the Rummels. The first church building was erected five years after the first service was held. In 1851, Carl Bauer left his Spring Branch property to his son, August, and moved with the rest of his family to Round Top, becoming one of the first settlers of the village.

Carl and his family were deeply religious and faithful in their endeavors to build a place to worship their Maker. The Bauers lost one child as an infant; their son, August, had preceded his family to Texas; one son, Karl, remained in Germany with all his descendants; four children were with them on their journey; and two daughters arrived a few years later. Like so many other families in the area, they had their joys and losses in the family due to illness and circumstances. Carl was driven to help establish and build the Bethlehem Lutheran Church in Round Top. By the mid-1860s, Carl, now almost seventy, led his sons, Carl Ehrgott and Carl Traugott, as well as his son-in-law, Conrad Schueddemagen, to complete Bethlehem Lutheran. His daughter, Wilhelmine Schueddemagen, was a strong asset as treasurer.

These two Lutheran churches are miles apart, but are connected by a family searching for a better place. Strong religious ties to their German Lutheran faith gave them the conviction to complete this task. Take a tour of these churches and cemeteries and you will find many of the same names in both St. Peter’s and Bethlehem’s histories and cemeteries. We are fortunate to have so many families in Fayette County, such as the Bauers and their descendants, who came to help build churches as evidence of their strong faith in God and family.

Bibliography:

Marler, Isla Bauer. “A Goodly Heritage”; Printit Office Suppliers, Uvalde, Texas, 1959

Obst, Rev. Martin H. and Banik, John G. “Our God is Marching On”; Von Boeckmann-Jones, Austin, Texas, 1966

Charles Bauer

By Connie F. Sneed

Mr. Charles Bauer was born June 5, 1845, at Oberensingen, Wurtemburg, Germany, a son of William and Margaret (Hahn) Bauer. His father was born in May, 1810, at the same location and was given a fair education. The education of Charles Bauer was secured in the public schools of his native country, which he was apprenticed to the trade of carpenter, thoroughly mastering every detail of that vocation.

Instead of going to Kentucky with the rest of the family, he came to Texas and located at Round Top, where he engaged in work at his trade. He was industrious and thrifty, and after a few years had accumulated money enough to go to Burton, Texas, and, engage in the lumber business, being associated with his brother under the firm style of W. Bauer & Brother. They bought out the first lumber yard established at that place and conducted it successfully for a period of twelve years, after which Charles Bauer disposed of his interests and went to Pomona, California. He first engaged in farming in that community, later became the proprietor of a feed mill, and finally opened a laundry, but after seven unprofitable years he decided that his best opportunities lay in Texas, and he happily returned to the Lone Star state.

Here, in 1894, Mr. Bauer entered the lumber business, buying out J. C. Hillsman & Son and conducting a lumber yard until April, 1914, when he sold out and retired from active participation in business operations. He was a stockholder in the Carmine Creamery and in the Oil Mill and a director and one of the organizers of the Carmine State Bank. He had been a farmer by proxy, his property consisting of 174 acres and being located in the Obediah Hudson League, near Carmine.

He took out his first citizenship papers at La Grange, Texas, and his final papers at Brenham, Texas. Mr. Bauer was married at Round Top, Texas, November 17, 1871, to Miss Mary Ernst, a daughter of Fred and Mary (Krum) Ernst.

Source: A History of Texas and Texans

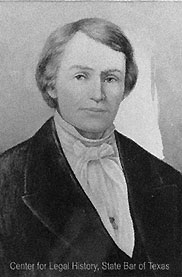

Robert E. B. Baylor

Politician, Soldier, and Preacher: Founder of Baylor University and Mary Hardin-Baylor University

by Katie Kulhanek

Robert Emmett Bledsoe Baylor was indeed a remarkable and memorable man. Skilled in both politics and religion, Baylor was a double-edged sword who worked for the betterment of society. Born on May 10th, 1793 in Lincoln County, Kentucky to Walker and Jane Baylor, Robert Baylor received his schooling at a small country school and later at several academies around Paris, Kentucky. He served in the War of 1812 and afterwards studied law under his uncle who was a judge. In 1819, Baylor was elected to the Kentucky Legislature and then when he moved to Alabama in the early 1820s, he was elected to the Alabama Legislature. Finally in 1828, he was elected to the US Congress.

Robert Emmett Bledsoe Baylor was indeed a remarkable and memorable man. Skilled in both politics and religion, Baylor was a double-edged sword who worked for the betterment of society. Born on May 10th, 1793 in Lincoln County, Kentucky to Walker and Jane Baylor, Robert Baylor received his schooling at a small country school and later at several academies around Paris, Kentucky. He served in the War of 1812 and afterwards studied law under his uncle who was a judge. In 1819, Baylor was elected to the Kentucky Legislature and then when he moved to Alabama in the early 1820s, he was elected to the Alabama Legislature. Finally in 1828, he was elected to the US Congress.