These histories were written by members of the Fayette County Historical Commission. They first appeared in the weekly column, "Footprints of Fayette," which is published in local newspapers.

By Gary E. McKee

The Marquis de Lafayette |

Fayette County, established in 1837, was named in honor of the Marquis de Lafayette. Lafayette, born in 1757, was orphaned at the age of 13, joined the French army as a cadet, and three years later married into nobility.

When the American Revolution began, Lafayette was a captain in the French Army. Against his aristocratic background, he supported the principals behind the Revolution, as noted in his memoirs that “my heart was enrolled in it.” King Louis XVI of France, seeking neutrality, forbade any assistance to the infant republic. However, Lafayette contacted an American agent in Paris and secured a commission as a major general in the Continental Army. The King issued an arrest warrant for Lafayette, but he left for America with eleven other European officers in May of 1777. By July, Lafayette had begun a life long friendship with George Washington, so much that Lafayette would name a son after him in later years. Lafayette commanded Revolutionary troops in numerous battles, wintered at Valley Forge, was wounded once, and was instrumental in the final battle of the American Revolution at Yorktown in which Lord Cornwallis surrendered the British Army. While many generals would have commanded from a safe place, Lafayette was always in the thick of battle with his soldiers. His respect of the ordinary working and fighting man would last for decades.

Returning to France after the American Revolution, politics had changed. He began his career as a politician during the French Revolution against the King. In the new government, with assistance from Thomas Jefferson, he presented the draft of a Declaration of the Rights of Man, which borrowed heavily from the American Declaration of Independence. Elected vice president of the Assembly, he spoke in favor of abolishing titles of nobility and renounced his own, though he was forever addressed as the Marquis. Lafayette was chosen as commander of the Paris militia, which he named the Garde Nationale. America’s National Guard derives its name from this militia. With the French Revolution spinning out of control, Lafayette spoke out on the excesses being committed, causing the new government to brand him a traitor. With the assistance of the American ambassador, Lafayette attempted to escape to America, but was arrested and spent five years in prison. The French revolutionaries demanded that his wife be sent to the guillotine, but the American ambassador threatened economic sanctions against France, so she was sent to prison with Lafayette instead, where future U.S. president James Monroe secured her freedom after a year. The French political tides changed and he was released through the efforts of American authorities in 1799. The new emperor, Napoleon, offered him a post, which he refused, choosing to become a gentleman farmer on his wife’s estate, which was named La Grange. In 1818, after the fall of Napoleon, he reentered public life advocating measures to advance the power of the people and representative government. This did not bode well with the latest French government, and in 1824, Lafayette accepted a timely offer to visit the United States as “the guest of the nation.”

Embarking on a 15 month tour through the 24 states comprising the U.S., he was honored at every stop. To celebrate his visit to his adopted country, Congress voted him the sum of $200,000 and gave him 36 square miles of land. (nice veteran’s benefits!!!!). The states of New York and Maryland made him an honorary citizen. (In 2003, Congress granted him honorary U.S. citizenship, one of only six ever awarded). Counties, towns, lakes, rivers, a mountain, schools, parks and streets were named after Lafayette or his French residence, La Grange. Wherever he went, large crowds of citizens cheered him and celebrations were held. The American citizens manufactured a variety of objects, including furniture, pipes, purses, flasks and money with his likeness imprinted on them. Presently there are over 600 entities in the U.S. honoring his name, including the first nuclear ballistic-missile submarine.

In 1834, Lafayette passed away in France at the age of 77. The U.S. went into mourning, and President John Quincy Adams delivered a two and a half hour eulogy to Congress. Anticipating his death, dirt from the Bunker Hill was sent to France and covered his casket; more towns and counties responded by adopting his name.

It was during this time (late 1820s) that William and Mary Rabb settled on the Colorado River just north of Moore’s Fort (presently La Grange). The Rabb family was from Pennsylvania. Rabb’s family had participated in the American Revolution, and Lafayette had under his command Anthony Wayne and his Pennsylvania Rangers. It is quite possible that the Rabb family had personal contact with Lafayette. At the same time that America was being consumed by Lafayette fever, immigrants from this America were settling the future Fayette County. His death in 1834 occurred during the forming of the La Grange area. Their admiration of this personification of freedom and the common man inspired the naming of Fayette County, Fayetteville, La Grange, and the local Masonic Lodge. When the town of La Grange was being planned, the streets were named after American and Texian heroes, i.e. Washington, Madison, Jefferson, Lafayette, Fannin, Crockett, and Milam.

The naming of this county and its towns over 170 years ago manifests itself in the independent spirit which is Fayette County today.

FYI:

by L. J. Calley

La Grange, Fayette County—names many of us use daily and know well. La Grange is a French term meaning, "The Meadows," according to Texas Excapes.com. It was the name the Marquis de Lafayette gave to his chateau thirty miles east of Paris. Fayette, La Grange—it is obvious that our forefathers name our county after this man, and our county seat after his home.

Why would a French nobleman merit such recognition and respect from circa q838 Texans? It's a long story that goes well beyond the space allowed here. In short, at nineteen Lafayette, whose wife was related to Louis XVI, went to America to become George Washington's aid during the revolution To Washington, who seems to have had the loneliest job in our history next to Abraham Lincoln, drew strength from Lafayette's total loyalty, his ear for staff intrigue, and most of all, his connections in Paris. Benjamin Franklin not withstanding, without Lafayette the alliance with France, which proved Engand's undoing, would most likely not have happened.

Returning home after our victory, Lafayette, to the detriment of his own fortune, promoted the idea of revolution in France, but during the Reign of Terror almost lost his head along with the rest of the French aristocracy.

As a prelude to the huge fiftieth anniversary celebration of our independence in 1826, President James Monroe and Congress made Lafayette an honorary U. S. Citizen and invited him to visit. In what he called his Farewell Tour, an aged Lafayette traveled our country by carriage, visiting all twenty-four states in 1824-1825, greeted everywhere he went by large crowds, parades, speeches, gifts, parties, and places named after him.

Lafayette died in 1837 and was buried in France in American soil, which he had taken home with him at the end of his farewell tour. La Grange and Fayette County were named in his homor by the Congress of The Republic of Texas folowing his death. The name, Lafayete, or Fayette appears almost 440 times as a place name in the United States. Fifty-seven are populated places, such as towns and counties, a fitting tribute to who has been, by far, America's most famous foreigner. Perhaps Washington's words in a letter to Lafayette dated April 28, 1788 express our own feelings toward him as well:

"The frequency of your kind remembrance of me, and the endearing expressions of attachment, are by so much the more satisfactory, as I recognize them to be a counterpart of my own feelings for you."

by Carolyn Heinsohn

Go west young man, go west! That was the slogan heard throughout the country in 1849 after gold was discovered the previous year at Sutter’s Mill in the Sierra Nevada Mountains in California. Gold fever attacked men in epidemic proportions, stealing away their sensibilities and filling their heads with dreams of prosperity. Thousands of men ventured westward in search of their fortunes with seemingly little forethought about the perils of crossing mountains and deserts to get to their destinations. There were others, however, who capitalized on the infectious malady by providing necessities to the affected multitudes who were heading west. These entrepreneurs became wealthy while remaining safe.

Upon hearing the news of the gold strike, men in Fayette County were also infected by the fever and were soon laying down their plows and leaving their weeping families, some never to return. The son of John Murchison, who lived in the Fayetteville area, was determined to not be left behind. Not wanting his son, Duncan, to go without him, John Murchison organized a gold -seeking group called The La Grange Company. On March 31, 1849, he advertised in a local newspaper that he was recruiting 100 men to join him on his journey to California. Approximately 42 men responded and joined Murchison with the hope that they would beat the odds and come home with a fortune in gold.

As they journeyed to California, the group divided at times or joined with other groups as they struggled to find a safe route through the rugged terrain that oftentimes hindered their progress. Bad weather, lack of water, food and supplies, poisonous snakes and Indian attacks were constant threats. Unfortunately, John Murchison was not one of the lucky ones! He died of an accidental self-inflicted gunshot wound and was buried where he died, never to be found again.

It was fortunate, however, that two men, Samuel P. Birt and John B. Cameron, kept fairly detailed journals of their adventures that began on May 1, 1849 with a total of 43 men and seven wagons. Six months later on November 10, 1849, the company finally reached its destination in California with ten men and three wagons, due to the other men venturing off alone or joining other groups.

Three of the 43 men, who ventured to California in The La Grange Company, are known to have returned to Fayette County. The names of the others who may have returned are unknown. Those three were Charles Helble of Biegel, Joseph Brendle, who lived in the Rutersville area, and Jacob Laferre of Ross Prairie. Helble and Brendle were listed among the remaining ten men in The La Grange Company at the end of their trip. Laferre was not listed, so undoubtedly, he was one of those who left the group somewhere along the route. It seems that Helble and Brendle, who left their families for up to four years, were not as successful with their gold-seeking adventures as Laferre, who came back to Texas with a sizeable fortune within two years.

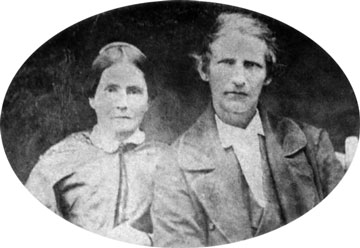

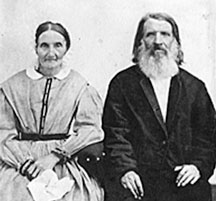

Jacob Laferre of French descent was born in 1823 in Bavaria, Germany. He immigrated to the U.S. in 1846, arriving in New Orleans with his 19-year old wife, Therese, and Caroline D’Later, also 19, whose relationship to Laferre or his wife is unknown. It is quite possible that since both ladies were 19 years old, they could have been twin sisters.

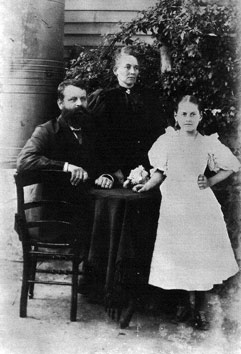

Laferre migrated to Fayette County where he purchased his first 50 acres of land in the Lucy Kerr League in April 1847 from William Luke. It is not known when Laferre’s first wife died, but he was back in Fayette County by February 24, 1852, when he married Caroline D’Later/DeLater, also of French descent. They had four children together: Carolina (Lena), born in 1854, who married Louis FrederickTiemann; Jacob, Jr. (Jake), born in 1856, who married Louise Stoecker; Charles A., born in 1859, who married Agnes Wolle; and Adolf J., born in 1862, who married Mary Giese. Caroline Laferre died in 1862, perhaps after the birth of Adolf. Laferre married his third wife, Fredericke Kaase, in 1867.

Deed records show that Laferre purchased and sold multiple tracts of land in the areas around Ross Prairie, Ellinger, Fayetteville, Biegel and Rutersville, as well as along Cummins Creek east of Fayetteville. Family tradition states that he concealed his money for a long while after returning from California, but records show that he was a money lender for a large number of people who were wanting to purchase land, but who had insufficient funds.

Deed records show that Laferre purchased and sold multiple tracts of land in the areas around Ross Prairie, Ellinger, Fayetteville, Biegel and Rutersville, as well as along Cummins Creek east of Fayetteville. Family tradition states that he concealed his money for a long while after returning from California, but records show that he was a money lender for a large number of people who were wanting to purchase land, but who had insufficient funds.

One of his tracts of land at Ross Prairie was sold to Henry Eilers, who established a cemetery on this land for his family. Laferre and his family continued to live on a nearby farm. When Frederike Laferre died in 1899, she was buried in the Eilers Cemetery. Jacob Laferre died at age 77 on August 26, 1901 and was buried next to Frederike.

Laferre’s probated will shows that his estate that was valued at $30,000 was divided among his children and grandchildren. Obviously, his success in the gold fields of California had a ripple effect for his family, friends and acquaintances, all of whom benefitted from his good fortune and generosity.

"Tis nine o'clock, and Duty calls to the Friendly Road; And you ride over the hills of beauty, bearing your precious load—News from the world's far places—." So wrote one southern mail carrier many years ago, in a poetic a tribute to the Rural Free Delivery Service called "On the Route."

Fayette County's rural carriers have traveled "on the route" for nearly 104 years. In fact, postal service officially came to Texas communities on August 1, 1899, when the first Texas Rural Mail Route station opened in La Grange.

In the early days, before Texas was annexed to the United States, post-riders carried mail between San Antonio and the viceroy of Spain in Mexico City. Mail carriers were mostly Indian runners, weather-hardened men of great physical endurance. Mail bound for points other than Mexico was carried horseback from Texas to Louisiana or Mississippi, then forwarded to its destination in the States.

The first regular postal system for Texas was inaugurated in December 1836, during the Presidency of General Sam Houston. But the Republic had no finances to adequately establish the system. The first Congress of Texas authorized the postmaster general to solicit funds from the public, and mail carriers were often paid in land.

Financial worries were not the only drawback to the early postal system. Bad roads, few bridges, and highwaymen lurking in out-of-the-way places posed enormous problems to the carrier.

After entering the Union in 1845, Texas was partly relieved of the responsibility of mail delivery when the state postal system became part of the national system. Longer routes were established, and much of the mail was carried in stagecoaches. One of the longest routes in the nation was from El Paso, Texas, to San Diego, California.

Around the turn of the century, the federal post office began experimenting with a mail delivery system with shorter routes, a system that could greatly benefit people living in the country.

"No one knows better than those living miles away from mail accommodations how unpleasant it is when work is plenty and urgent upon the farm to take the time to ride or drive to the post office," wrote a La Grange Journal reporter in August 1899.

To alleviate the problem, and to make mail accommodations as complete as possible, the federal government established several test routes to determine the feasibility of a rural delivery system. As the Journal shared with readers, "the authorities have thought favorable enough of this community to make it one of the experimental stations."

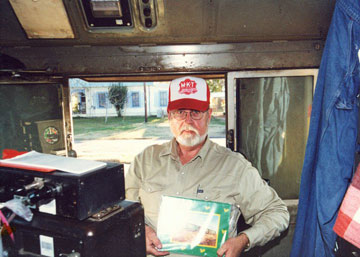

The route entailed twenty-three miles of travel in Fayette County and served about 685 people. Laid out by the national post office department in Washington, the route went as follows: "Beginning at the bridge west of La Grange, go west one mile on the La Grange and Cedar Road; thence north on the La Grange and Plum Road to Manton Sand Ridge; thence west over MKT track over road by W.J. Kirk's place about three miles; thence south between Jos. Brown and Max Wildner's farms to La Grange and Cedar Road; thence to the Cedar post office; thence southeast to Parma's Store to Schulenburg and La Grange Road via Bluff post office and back to La Grange."

Henry Cremer was the contractor, and Ernst Prilop served as the postmaster at the Cedar Post Office when the rural route was established.

According to a January 1945 report in The Texas Carrier, the "first rural route" question was raised in 1933, when Hillsboro also claimed the honor. The question was aired in several daily newspapers, including the Dallas News. After much debate, and with the assistance of State officials, a marker was granted to commemorate and permanently mark this location, thus settling the issue.

Since it was a state incident and not a national one, the marker could not be erected on Post Office grounds. So the City of La Grange granted permission for its location on a site adjacent to the post office, on land that was not officially U.S. government property. Etched in a brass plate mounted on red granite, the marker proclaiming "The First U.S. Postal Rural Mail Route in Texas" graces the lawn at the corner of Colorado and Jefferson streets.

The Rural Letter Carriers Association of Fayette County had charge of the dedication ceremonies when the marker was erected by the State of Texas in 1936, the state's Centennial Year. A large number of citizens from La Grange and across Texas attended, as well as the 57 post offices in District No. 9. John L. Giese, the Rural Letter Carriers president, and mail carrier Chas. C. Albrecht organized the event.

A similar celebration was held on August 2, 1999 to commemorate the 100-year anniversary of the Texas Rural Route System. A unique cancellation device, designed by local artist Sally Maxwell, was used on that date for outgoing mail. Linda Kossa, a La Grange post office employee, worked from an antique window in a special model post office brought in from Gonzalez for the occasion. Formal ceremonies held on the Fayette County Courthouse square attracted many local citizens and dignitaries, as well as guests from across the state and nation.

During the anniversary celebration, Fayette County Judge Ed Janecka remarked on the importance of the rural mail system, noting that its establishment was instrumental in developing Texas. Certainly, throughout its century-long history, it has proven to be a tremendous benefit to people living in the country. And though the routes are different and the mode of transportation has changed, today's rural mail carriers continue to "make mail accommodations as complete as possible."

A New York post office opened in 1914 with the declaration that "neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds." Although this is not an official post office motto, it is nevertheless embraced by many in the U.S. Postal Service.

Indeed, that rural carrier and poet from the South, writing many years ago, echoed the sentiment, and no doubt Fayette County's mail carriers throughout the century understood. "Folks for their mail are calling—It's more than determination—it's something one can feel—a sort of exultation to the [One] behind the Wheel, That drives him into action, and a sense of duty done, Brings a thrill of satisfaction when the battle has been won."

by Connie F. Sneed

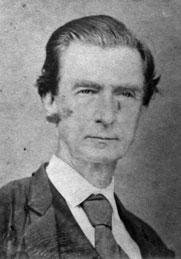

Jonathan Lane, a founder of The First National Bank of La Grange, was a cowboy, attorney and state senator. He was also a descendant of David Crockett of the Alamo fame.

Born in Decatur, Alabama in 1853, he was the son of Charles Joseph and Ellen (Crockett) Lane. His father was a Methodist minister, and his mother was a niece of David Crockett. At the age of 18 months, he was brought to Fayette County where he received his schooling. After graduation, he went to Goliad County, where he worked as a cowboy until he was 25 years old.

He then became a clerk in the J. M. Harrison General Merchandise Store in Flatonia. During his leisure hours, he studied law and courted Miss Alma Harrison, the daughter of his employer. They were married on December 29, 1876 and had a daughter, who died in Houston about 1906, and an adopted son. Lane was admitted to the Texas bar in 1880.

He practiced law for several years in Flatonia and then later associated himself in La Grange with R. H. Phelps and J. C. Brown. The firm later became known as Brown, Lane & Garwood. From 1887 to 1891, Lane served in the state senate. While in the senate, he was named as a director of the First National Bank which was founded in 1888.

Lane later went to Houston and became a member of the law firm, Brown, Lane, Garwood & Parker. He also became very active in business ventures. He served as president of the Cane Belt Railroad, a 119 mile line that became a part of the Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe System. He served as president of the Thompson Brothers Lumber Company of Trinity, a company with capital stock of $1,500,000. He was also president of the American Surety and Casualty Company and of the Guarantee Life Insurance Company.

He was a member of the Democratic party and served as chairman of its state convention in 1892. He was a Shriner, Mason, Knight Templar, Knight of Pythias, and Methodist. Lane died at Port Aransas on May 27, 1916, and was buried in the Flatonia City Cemetery.

According to an article in the Houston Post dated May 28, 1916 reporting Lane’s death earlier that week, it was written that “while always taking an active part in political affairs, Mr. Lane held only one political office in his life….His judgement on party matters was trusted by practically all the political leaders of the state.”

Honorary pallbearers included Gov. James E. Ferguson, Lt. Gov W.P. Hobby, and several judges. In an eulogy passed by the Harris County Bar Association, Lane was described as a “manly” man. He inherited the traits of courage and devotion to which he conceived to be the right from a father who amid the early settlements of a new county consecrated himself to the service of God and his fellow man.

The Latins were a group of young people who lived in and around the Bluff area of Fayette County during the 1840-1860 time period. They were so named because of their education and cultural background. They had emigrated from the small principalities of Central Europe in order to give their children better opportunities. These people hoped to find in Texas the democracy and freedom that had been denied them in Europe. Many of the Latins were political refugees who had taken part in the republican revolution of 1848.

The Latins were proud of their culture and education and often found it difficult to adjust to their new rural surroundings. One young woman wrote to a friend in Europe complaining that there was little mental stimulation in the daily life on a farm. She wrote that each day suffered from "eternal sameness" and was "painfully monotonous." In her desire to learn she often spent countless hours studying alone.

About 1857 things changed for the young Latins of the area when a local German poet, Johannes Romberg, formed the Prairie Blume Literary Society at Black Jack Springs. It was one of the first literary societies in Texas. The society published a journal featuring literary contributions from its members. The journal was named the "Prairie Blume" because the prairie flower symbolized prose and poetry.

The young Latins anxiously awaited every meeting of the society. It was nothing for them to ride fourteen miles on horseback just to attend one of the meetings. They were much more formal than is customary today. Julius Willrich would often ride to a member's garden gate and invite them to the next meeting with these words: "I have the honor to invite you to the next meeting of the Prairie Blume at our house." Various families took turns in entertaining the group of young scholars.

At meetings intellectual games were often played followed by a flute solo or a violin concerto. The young Latins discussed many subjects including the political and social conditions in the world. They would often spend hours philosophizing over books they had read or writing down these thoughts to contribute to the next issue of the journal. Today some copies of the "Prairie Blume" still exist.

At the outbreak of the Civil War the activities of the organization declined as many members joined the military. After a few more years the society was discontinued entirely.

By Carolyn Heinsohn

Having had a great aunt and uncle, who lived here in Fayette County during a time when others had advanced to a lifestyle of modern conveniences, I was given the opportunity to witness a lifestyle of the 19th century, because they chose to remain in a time warp. A few of my memories include my great aunt’s laundry and ironing practices, some of which would have been rarely experienced by someone in my generation.

Since no detergents were readily available for laundry, scrubbing floors or doing dishes, homemade soap had to be made prior to doing any cleaning chores. Until lye balls or canned lye was available, my aunt first had to make lye by putting ashes from the wood stove and heater into a barrel and adding water. The ashes would settle to the bottom of the barrel, and in a few days, there would be strong lye water, which would be cooked with lard or bacon skins in a large iron wash pot. A chemical reaction would take place, turning the ingredients into a strong, smelly, unattractive-appearing soap that was cut into chunks.

Doing the laundry was an all-day job. Wet soap was rubbed onto their soiled clothing, which was then rubbed on a scrub board before being placed into a large wash pot that was placed over a fire. The wash pot had to be filled with bucket after bucket of water carried from the well. The clothes in the wash pot were agitated with a large wooden paddle until my great aunt thought that the clothes were clean. She would then remove the clothing with the paddle and rinse them in clear water in a washtub. Sometimes the white clothing was rinsed a second time in water with Mrs. Steward’s Bluing, which was a fabric whitener. The clothing was then wrung out by hand and hung on a clothesline to dry. Handling bed sheets and heavy clothing was quite a chore. Wind would occasionally blow clothing off of the clothesline into the sand and dirt, or frigid temperatures would freeze the clothing into a stiff “board”. Everyday work clothing had to be made with heavy duty fabric in order to withstand the harsh soap, scrubbing and boiling water that were necessary to get them clean. Sunday clothing was washed infrequently. My great-aunt’s “better” dresses, some of which were made of finer fabrics, were hand washed only when absolutely necessary. Usually, they were spot cleaned and hung up to air out. My great uncle’s only suit was made of wool, so it was never washed, because woolen fabric would shrink. There were no dry cleaners for non-washable fabrics, nor would they have spent the money for such frivolities. His dress shirts were washed perhaps after every second or third wearing.

Their first electric wringer-style washing machine was purchased after they obtained rural electricity. Prior to electricity, earlier styles utilized kerosene to run their motors, but my great aunt and uncle never owned one of those machines.

Ironing was another all-day chore. All of my great-uncle’s dress shirts, some of my great aunt’s dresses, aprons, their pillow cases, dresser scarves and doilies were dipped in cooked starch and allowed to dry. Then they were “sprinkled”, using a Nehi soda water bottle and a sprinkler stopper. The clothing was rolled up, placed inside a pillow case and allowed to “set” before ironing. Their first irons were flat irons or “sad” irons, which were V-shaped pieces of iron with handles across the top. They were placed on top of the wood stove to get hot, so it was beneficial to have two irons in order to have one hot iron to work with while the other was re-heating. Later they had hollow irons, so that hot coals could be placed inside. All of these irons were very heavy and were never reliable insofar as how hot or cool they were. Oftentimes, these irons left spots of soot on their clothing, which created more work for my great-aunt.

Laundry and ironing practices have changed drastically through the years. Fortunately, I still have a couple of old scrub boards and irons in my possession to remind me that I should never complain about having to press a few items of clothing after removing them from my clothes dryer that has a wrinkle-free cycle. Sometimes we need a “wake-up call” to remind us just how fortunate we really are!

By Stacy N. Sneed

This article is taken from Flake’s Bulletin of 03 Mar 1867

“A company of infantry is stationed at Round Top, Fayette County, Texas. On the 8th instant a rowdy of the neighborhood passes through the camp of the company and deliberately shot off his revolver among the soldiers, fortunately doing no damage, he put spurs to his horse and succeeded in making his escape, although the men fired their guns after him.

The citizens of the place furnished the soldiers with horses and revolvers, and the commander of the camp took a party in pursuit, following the would-be murderer five miles, overtaking him at Cumming’s Creek. Refusing to surrender the troops fired a volley at him, and think him killed, although he and his horse disappeared in the brush, and night prevented further pursuit. There have been seven murders committed in Round Top within the past twelve months, all owing to the fact that the civil authorities are impotent against a few lawless vagabonds.—San Antonio Express March, 15.

We believe the above to be true, because it accords with explanations given at headquarters of the frequent escape of these outlaws. Red tape so binds our military that with thousands of revelers rusting in the arsenals and cords of carbines, our soldiers cannot get hold of them, but must borrow from citizens when going into a fight. Imagine a scene like the above and then think how inexpressibly funny it must be to see soldiers running to all the corner for groceries for weapons, because a fight is on hand. Horses innumerable scour the plains of Texas and yet soldiers ride borrowed nags--this red tap, this is system, this is downright nonsense. We have no patience with this way of doing business. In these days of emancipation, we ought to emancipate our offers from the bondage of red tape.”

During the second year of the Republic of Texas, Fayette County was created out of Bastrop and Colorado Counties on December 14, 1837 and officially organized in January of 1838. But beginning in 1821, some seventeen years prior to that, the land that would make up Fayette County was a part of Stephen F. Austin's first colony, granted in early 1821 by the Spanish Governor of Texas.

Austin had been given the right to settle three-hundred Anglo-American families in Texas, and almost immediately the first of those settlers began arriving to lay claim to land, mostly along the Colorado and Brazos Rivers.

Then in 1822, after only about one hundred of those families had arrived in Texas, the Mexican Revolution successfully overthrew the rule of Spain. Suddenly Austin's colony was in jeopardy and he was forced to leave Texas and travel to Mexico City to convince the new Mexican government to approve his grant of land.

While Austin was in Mexico City for over 16 months in 1822 and 1823, his first settlers were not finding Texas a very hospitable land. A crop failure and increased problems with various tribes of Indians seriously threatened the success of the venture. There were also no Mexican Army troops in Texas to help guard against increasing instances of theft, intimidation and the attack on the few settlers by hostile Indians. New immigration into Austin's colony stopped.

Luckily for all concerned, the Mexican Governor of Texas, Jose Felix Trespalacios, recognized the delicate balance between success and failure of the colony. As a result, Governor Trespalacios sent Baron De Bastrop to the settlements on the Colorado River in December of 1822, authorizing the settlers to organize a militia command to defend against hostile Indians and also elect two alcaldes, or Justices of the Peace. One of those magistrates was elected in the "Colorado District" and the other in the "Brazos District" to rule on civil and criminal matters. The Colorado District was the first governing body organized in what would eventually include Fayette and Colorado counties.

Then just two months later on March 5, 1823 the alcalde, in the Colorado District, John Tumlinson, Sr., wrote Baron De Bastrop in San Antonio, that "I have appointed but one officer who acts in the capacity of constable to summon witnesses and bring offenders to Justice, yet a few complain of the expense which I thought as reasonable as could be allowed for the time and trouble of so disagreeable an office, to wit at the rate of five cents per mile--."

When taken with other records, it is confirmed that a constable, not a ranger, a marshal or a sheriff was the first lawman in Anglo-American Texas, and that the attitude of "a few" toward this office has not changed in almost 180-years.

by Connie F. Sneed

William Hamilton Ledbetter, Fayette County attorney, was born to Hamilton and Jane (Peacock) Ledbetter, a well-to-do Tennessee Episcopalian couple, in 1834. In 1840, the family moved to Texas and settled with a large number of slaves near the site of present-day Victoria. Four years later, the Ledbetter family moved to Fayette County and established a small plantation there.

William, the third of nine children, was educated in Fayette and Washington counties and began to study law in 1855. He was admitted to the bar in 1857 and set up a lucrative practice in La Grange, the seat of Fayette County. In 1862 he was commissioned a lieutenant in Company I of Col. George M. Flournoy's Sixteenth Confederate Texas Infantry. Ledbetter subsequently fought in a number of battles in Louisiana, including Perkins Landing, Millican’s Bend, and Mansfield. In 1863 he was captured by Union forces at the battle of Pleasant Hill; he was freed in an exchange shortly thereafter.

Later that year, having been mustered out of the Confederate Army, he went to Austin as a representative in the lower house of the Tenth Legislature. He returned to Fayette County in 1865, nearly bankrupt as a result of losing twenty slaves and a good deal of valuable property in the war. He once again took up the practice of law and in 1876 was elected as a Democrat to the Texas Senate, where he served until 1880. He thereafter served several terms as mayor of La Grange. Capt. Ledbetter was one of the most prominent citizens of Fayette County.

Ledbetter was married twice. His first wife, Elizabeth “Bettie” (Pope), died in 1864 at the young age of twenty-five, leaving two children, William Hamilton Jr. and Elizabeth Nina – both of whom were born in La Grange. In 1868 William Ledbetter married Tennessee “Tennie” Hill; four or five of their children died in infancy, but two survived, Emmet and Aline.

William Ledbetter was found dead on April 24, 1896, in his home in La Grange by his wife upon her return from a trip to Virginia. His family had been away from home and he been taking his meals at the hotel in La Grange. He had also been out and about the day before he passed away. Death was believed to result from heart failure. It is this man that town of Ledbetter, Texas is named after.

by Donna Green

Generosity and appreciation are two qualities which have always been abundant in American soldiers as they served around the world in various wars and police actions. Private Joseph P. Lev of Praha, Texas was no exception. Private Lev was twenty-six years old when he was a soldier serving in New Guinea. He was shot in the stomach by a Japanese sniper in late July, 1944. As he lay dying, Lev begged a soldier friend of his to write his parents a letter regarding his last will. He wanted all the money that was his life saving to be given to the missionaries in New Guinea. Lev had personally been witness to the hard work and extreme conditions under which the missionaries worked.

Generosity and appreciation are two qualities which have always been abundant in American soldiers as they served around the world in various wars and police actions. Private Joseph P. Lev of Praha, Texas was no exception. Private Lev was twenty-six years old when he was a soldier serving in New Guinea. He was shot in the stomach by a Japanese sniper in late July, 1944. As he lay dying, Lev begged a soldier friend of his to write his parents a letter regarding his last will. He wanted all the money that was his life saving to be given to the missionaries in New Guinea. Lev had personally been witness to the hard work and extreme conditions under which the missionaries worked.

In February, 1945 the Society of the Divine Word Missionaries was notified by letter of Private Lev's generous bequest. The letter received at the headquarters of the mission in Illinois was from the Reverend John Anders. He was pastor of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary church at Praha. The letter explained that Private Lev had always had a great interest in foreign missions and was an ardent supporter of their work.

Private Lev has a marker in the cemetery at Praha. The marker states that he was killed in action on Luzon Island. Luzon is an island in the Philippine archipelago. This is several hundred miles from New Guinea. According to a telegram from the War Department Private Lev was buried in the United States Armed Forces Cemetery, Finschafen, New Guinea, No. 1, Grave 787. This cemetery is located on the east coast of the Huon Peninsula, approximately 50 miles north of Port Moresby, New Guinea.

Private Lev was born August 12,1918 in Praha. He was the son of Emil and Marie Lev.by Carolyn Heinsohn

The following excerpts about life in early Fayette County were taken from the “Sketch of Fayette County” compiled by Laura J. Irvine in 1880 for The American Sketch Book, an Historical and Home Monthly:

“J.G. Robison was the first to represent this district in the First Congress that convened at Columbia, on the Brazos, in the latter part of 1836 and in February, 1837. He had just returned home when he and his brother, Walter Robison, were both on their way to see a gentleman on business and were killed by the Indians on Commings (Cummins) Creek. The same day Mr. and Mrs. Gocher were killed by the same party of Indians on Rabb’s Creek, and three of their children carried off as captives, one girl and two boys; they were afterward redeemed by a Mr. Spalding, who married the young lady.”

“The first court held in Fayette County was in the town of La Grange in a little log cabin.”

“Mr. John E. Lewis, Sr., a veteran of the war for independence, moved to Fayette County in 1833, participated in the Battle of San Jacinto, and he together with J.H. Moore, had the pleasure of guarding the captured Santa Anna. He was the first justice of the peace commissioned in the county.”

“John Breeding, one of the old settlers of Fayette County, came to Texas in 1832…He was the first sheriff of Fayette County under the Republic…He died in October, 1869.”

In 1880, “Fayette County has four Texas veterans still living that fought in the Battle of San Jacinto in 1836: Col. Monroe Hill of Fayetteville; I.H. Hill of Round Top; Col. Joel W. Robison of Warrenton; and John E. Lewis of La Grange.”

“The first cotton crop raised in this county was in 1834 on the farms of Jessie Burnham and Jack Crier.”

“In 1842, the Indians killed one of old Mr. Earthman’s sons and ran another son until he went blind from over-heating and so remained the rest of his life.”

“The last Indian raid in this county was in 1843. Mr. John Lewis says that the Tonkaway (Tonkawa) tribe would occasionally camp on O’Quinn Branch.”

“The first whiskey sold in La Grange was brought by a man who went to Houston and sold his horse for a barrel and brought it back on a ‘Truck Wagon’ with oxen attached.”

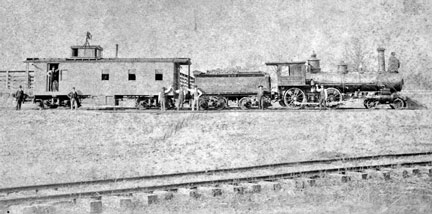

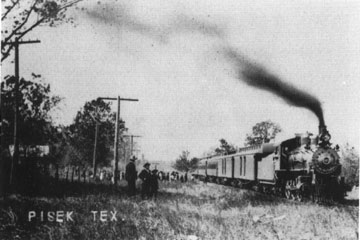

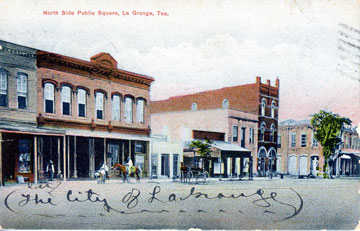

“The Galveston, Houston and San Antonio railroad has a branch running from Columbus to La Grange, thirty-one miles. Cars commenced running to that place on the first of January, last 1880.”

“Bradshaw and White have erected a large warehouse at the depot…Mr. Shumacher has built at the depot a splendid ice house…”

“La Grange has three hotels. The most popular is the ‘Farquhar House’, W.E. Farquhar, proprietor. It is a two-story building and very convenient for businessmen.”

“The La Grange Journal has lately been purchased by Messrs. Bradshaw, Holloway and Bryan, and is edited by the able editor, Lewis R. Bryan. The Journal is a weekly newspaper….”

“The Slovan is published in La Grange and is the only Bohemian paper published in the state. It is a splendid forty column paper, well supported.”

by Katie Kulhanek

Livingston Lindsay was born in Orange County, Virginia on October 16th, 1806. It is said that Lindsay’s mother (a devout Episcopalian) “carried him some forty miles on horseback as an infant so he could receive the sacrament of baptism”. After graduating from the University of Virginia, he moved to Hopkinsville, Kentucky where he studied law. After practicing law a short time, he moved to Princeton, Kentucky and taught school. In 1860, at the age of 54, Lindsay moved to Texas and began practicing law in La Grange. The move was not centered around his career, but rather because he intended to join his daughter there.

Livingston Lindsay was born in Orange County, Virginia on October 16th, 1806. It is said that Lindsay’s mother (a devout Episcopalian) “carried him some forty miles on horseback as an infant so he could receive the sacrament of baptism”. After graduating from the University of Virginia, he moved to Hopkinsville, Kentucky where he studied law. After practicing law a short time, he moved to Princeton, Kentucky and taught school. In 1860, at the age of 54, Lindsay moved to Texas and began practicing law in La Grange. The move was not centered around his career, but rather because he intended to join his daughter there.

After settling in La Grange, Lindsay joined The Volunteer Aid Society. The society was organized to aid families whose fathers and sons had left their farms and homes to go fight during the Civil War. Lindsay had a son-in-law (Ben Shropshire) who was fighting in the war. Shropshire later became known as a popular Confederate hero.

While in La Grange, Lindsay had a clash with a townsman. One August morning at about 9:00 a.m. in 1867, Lindsay got into a confrontation with Dr. J.P. Brown in front of G. Friedberger’s store and stabbed Brown. Despite his action, Lindsay only had to post bond and “suffered no further punishment”. The ordeal must not have had much of an impact on his reputation. He was appointed an associate justice of the Texas Supreme Court about a month later.

After the war in 1867, US military authorities replaced the current members of the Texas Justices of the Supreme Court (who had been Confederate supporters of secession and were considered hindrances to reconstruction) with justices that would adhere more to the needs and orders of the U.S. government. Lindsay was appointed as one of these new justices on September 10, 1867 by the occupying Union forces because of his moderate views and general dislike for slavery. Together, these justices formed a Military Court of justices in Texas during the Reconstruction era. Lindsay’s views on slavery enraged local residents of Fayette County. At that time, the area was occupied by federal troops, but there were many confrontations between the troops and the ex-Confederate soldiers of Fayette County.

It was at about this time (fall of 1867) that the Yellow Fever epidemic hit La Grange. Texas governor Elisha Pease made Lindsay his correspondent for La Grange during the epidemic. From August to December 1867 the fever struck the town of La Grange taking as many as 240 people—20% of the town’s population. Livingston himself was affected; several of his family members contracted the disease. His concern can be seen in his letter written to Governor Pease in October of 1867:

My Dear Sir:

Our mutual friend, Dr. M. Evans, and his daughter, very unexpectedly to me, and to my great surprise, from the report I had heard of their cases, both departed this life last night, and will be buried to day. The Epidemic has not abated here, so far as there are subjects left for its actions. I have three new cases, in the past thirty-six hours, in my own family. Whether they will be fatal, or not, I cannot judge, till further developments. This leaves only two in my family yet to have it -- a grand child and a servant.

I don't know certainly -- but it does appear to me that this favor [sic] has proved more fatal here -- than it has ever been anywhere in the South, or even in the West Indies. Just to think of it -- one hundred and seventy deaths, in a period of a little over four weeks, in a population, all told, of not more than 1600, when all the re-sidents were at home; and during the Epidemic, more than half; yea, I believe, two-thirds of the population, had fled their homes! I trust the malady has nearly spent its force, and our afflicted people may soon be relieved from this awful visitation. With my best wishes for your health and happiness,

I am, your friend, & obt. Sevt.

Livingston Lindsay

N.B. I am almost worn down with care and nursing, and I am fearful I shall not be able to reach Austin as early as I anticipated. But, as soon as I can come, in justice to those dependent upon me, I will come.

L.L.

The Yellow Fever disease first hit Galveston repeatedly, but in the fall of 1867, it came inland, wrecking more havoc. The mortality rate is thought to have reached as high as 85%. The disease could strike quickly too; a person could be healthy one day and then dead three days later. In La Grange, people died so quickly that the funeral homes had no room to store the bodies. Sometimes they were piled inside the cemetery grounds where they were later buried in large, circular shaped mass graves.

Lindsay’s political views were more radical when compared to the average Fayette County citizen of the time. However, there were instances in which Lindsay stayed conservative. Southwestern Historical Quarterly explains a case involving the selling of slaves in1865 in which Lindsay allowed the sale of slaves despite the arrival of the Emancipation Proclamation in Texas in June of 1865. He believed that even though Juneteenth was “the day of jubilee of the freedom of the slaves in Texas” the buying and selling of slaves in Texas was lawful before June 19th.Generally though, Lindsay was against slavery. He believed that the Thirteenth Amendment (freeing slaves) was “not necessary to destroy slavery in Texas” because it basically “finished the work throughout the entire nation”. It is noted that in 1868, local Fayette County blacks marched military style and with arms into La Grange to vote. Their response to those asking why they came this way with weapons was that Lindsay had warned them it would be needed for their protection.

Lindsay was one of the more moderate members of the Constitutional Convention when he attended it from 1868-1869. Subsequently, he was judge of the district composed of Colorado, Fort Bend, Washington, Austin, and Wharton counties. Lindsay served on the Texas Supreme Court as a justice until 1869 when the court was reorganized and the number of judges was reduced from five to three. Lindsay was a member and Senior Warden of St. James Episcopal Church in La Grange and at one point served as lay reader for the church when Reverend W. G. W. Smith became sick. He also served as Fayette County Attorney in the 1880s. Lindsay died in La Grange in 1892 and is buried in the Old La Grange City Cemetery.

Henry Charles Loehr was born Jan 30 1862, in the Bluff community. As a 16 yr old, he rode a freight train to the state of Illinois. There, Henry attending the Weltner School of Healing and supported himself by working on a farm growing corn. After graduation, he returned home.

He worked on the family farm for a while and courted Anna Hausmann. Henry then traveled to West Texas, settled near San Angelo and engaged in sheep farming. One year later, he returned home to claim his bride, Anna, whom he married in 1889. He took his new bride and returned to West Texas. The couple was blessed with one son, Robert, born in1891 in Irion County. After several more years of ranching, Henry decided to return to La Grange.

His success in the sheep industry allowed Henry to rent a complete train to relocate his homestead. In one railroad car, he put all his sheep, and another he loaded with his horses, buggy and wagon. A third car was filled with his household items and supplies. Henry, Anna and Robert enjoyed the ride in a Pullman car all to themselves.

They arrived at the La Grange stock pens, and were met by Anna's brother, Louis. From the stock pens, they drove Henry's sheep across Buckner's Creek bridge and up the old Bluff Road (now Country Club Drive) to the land, which is now the Loehr Ranch. He quickly resumed his ranching business, where Henry, an expert with a rope, was known by all as "Being Born in the Saddle."

Henry's reputation as a faith healer took root. From ledgers handed down through the family, the clientele list was very large. His healing was much like acupuncture and chiropractic medicine. Patients would come from miles around and wait their turn sitting on his front porch, to receive healing. He was strong in his convictions and stressed daily to all his patients that "all healing came directly from God." (thus he was known as a faith healer.) He also gave "absent" treatments, whereby he would sit and meditate on a patient who might not be able to come to him for treatment. The ledgers show the names of many influential people from Fayette County who paid 25c to $1 for a treatment. He healed people for over 40 years until his death.

Mr. Loehr had a very gentle nature, but was stern in idealistic values. He was in love with nature and went to all means to protect it and taught his son, Robert, to do the same. Henry died in 1948 and Anna died on June 3, 1955. Both are buried with the Loehr family members at Williams Creek Cemetery.

The home in which he practice is still located on the bluff and is owned by the Lloyd G. Loehr family and is being restored to its original state as much as possible.

by Rox Ann Johnson

You've heard of people being in the wrong place at the wrong time. A travelling couple's stop to rest at Carmine in 1930 could have cost them their lives at the hands of local law enforcement.

You've heard of people being in the wrong place at the wrong time. A travelling couple's stop to rest at Carmine in 1930 could have cost them their lives at the hands of local law enforcement.

It had all started with an attempted robbery at the Round Top State Bank. Very early on the previous Saturday morning, A. L. Krause, who lived across the street from the Round Top bank, was awakened by the steady noise of a hammer coming from the direction of the bank. He tried to call Sheriff Will Loessin in La Grange, but no one was awake to make the connections for the call. He then began firing his shotgun to rouse his neighbors and three men were seen running toward their car, leaving their pliers, crowbars, etc. behind at the bank. They had entered through the back door and had been attempting to dig through the seven-layer brick wall of the bank vault. The sheriff was finally reached by telephone "in a round about way" and found fingerprints and other clues, but did not catch the culprits. This set the scene for what happened in Carmine the following Friday morning.

Local newspapers differed on whether the couple had traveled from Illinois or Indiana, but on Thursday evening, November 13, Mr. J. J. Day, a traveling salesman, and his wife, Doris, were en route from Houston to Austin. A storm was approaching and Mr. Day stopped at Carmine to rest. Parking near a filling station seemed like a safe place to spend the night, so Mrs. Day took the rear seat while Mr. Day slept on the front seat.

The storm came through after midnight, accompanied by lightning that struck a wire leading to the burglar alarm in the Carmine State Bank. Sheriff Will Loessin was alerted and, with Deputy T. J. Flournoy, sped over to Carmine where they noticed the out-of-state license plates on the parked Day automobile.

Sheriff Loessin approached the auto and demanded that any occupants get out. The travelers were awake by this time and, while trying to sit up, Mr. Day accidently set off his car horn. Having just dealt with the attempted robbery in Round Top, the sheriff thought Mr. Day was signaling accomplices. He opened fire on the car, hitting the wife with buckshot in the back and hip as she rose from her prone position. Much to Sheriff Will's distress, her wounds were serious enough to summon an ambulance to take her to La Grange. Surgery was performed and a week later she was still recuperating in the hospital, while the embarrassing story made the rounds in area newspapers.

The 1930 episode was just a false alarm, but the Carmine bank was indeed robbed in 1932, in 1933, and again in 1997.

from the La Grange Journal files at the Fayette Heritage Museum and Archives

On April 16, 1934, "Commissioners' court met in special session Monday morning, having several important matters to be acted upon and without much delay set to work. Unanimous was the decision of the members to buy a modern machine gun for the sheriff's department. This will enable the sheriff and his deputies to cope with the situation, should it materialize, when bandits invade a section and drive all opposition before them because of their machine gun fire."

Apparently the procurement processes in 1934 were a lot more streamlined than today because three weeks later in the May 3 edition of the journal this article appeared:

"The machine gun, ordered and purchased by the Commissioners' court for the sheriff's department recently, was received last Monday, and the news spread among the boys on the street rapidly. All had to take a look at the fast repeater, and see how it "worked." What to the bank robbers is "an old thing" to the peaceful citizen is new, and had to be seen."

"Deputy Jim Flournoy was showing it to several late in the afternoon, and was pointing it out of the window while explaining its operation. The Journal desires not to be funny, in mentioning this, but Jim did not notice what several others noticed. Out in the street, and standing near to an automobile, was a salesman, he had probably placed some groceries in the vehicle. When he saw the machine gun pointed directly at his body, and Jim Flourney wafting it from sided to side, this salesman became nervous."

"Small thing this machine gun, almost a toy, but $250 for it makes the blamed think look larger. Maybe it will not have to be put to use, can't say; but, the reader will remember the remark of the old woodsman who had neglect a part of his raiment: "Well, the Good Book says, ye must always go prepawed."

This equalizer is believed to still be in the arsenal of the Fayette County Sheriffs Department.

By Rox Ann Johnson

Many years ago, the late La Grange historian, Verna Reichert, first told me the story of Nellie Mann, the little girl who lies buried beneath a Victorian playhouse in the Old La Grange City Cemetery.

Nellie was born in La Grange one hundred twenty-five years ago on September 25, 1892 to Mr. and Mrs. Adam S. Mann. Her mother Marie Price Lane, known as "Ridie," was born at Oso in southwestern Fayette County to Rev. Charles J. Lane, a Methodist preacher and farmer who later became a Flatonia merchant. Two of Nellie's maternal uncles represented Fayette County at the State Capitol. Jonathan Lane served two terms as a state senator, while his brother, Charles E. Lane, served two terms as a state representative.

Ridie and A. S. Mann, a native of Illinois, married in 1889 and made their home in La Grange. A daughter, Vivian, was born in 1890 and then Nellie arrived two years later. She was described as a bright and merry child, both lovely and loving. On the Christmas Eve that she was five years old, Nellie, her sister, and another little girl were playing near a fireplace in her home on South Main Street when her clothing caught fire. Her mother heard her screams and rushed in and wrapped her in a foot mat to extinguish the flames, but Nellie's back had been burned raw and part of her hair was burned to her scalp. Local newspapers reported the accident and, for a while, it looked as though she would recover, but on Monday night, January 3rd, 1898, Nellie passed away at her home. According to The Journal, the sad words, "Nellie is dead," passed from lip to lip. She was laid to rest in the Old City Cemetery the following day.

Nellie's heartbroken parents had a fanciful gazebo-like structure built over her grave. Mrs. Reichert told me that it had curtains that were drawn on stormy nights, because little Nellie was afraid of storms. Its corner posts held shelves for small toys that might amuse her.

Nellie's heartbroken parents had a fanciful gazebo-like structure built over her grave. Mrs. Reichert told me that it had curtains that were drawn on stormy nights, because little Nellie was afraid of storms. Its corner posts held shelves for small toys that might amuse her.

A younger brother, Roy, was born in 1900, but the family was soon split even further apart. Though the couple remained married, Ridie moved with her children to Houston where she lived for the rest of her life. Adam Mann stayed in La Grange, boarding in other people's homes as he served Fayette County as deputy county clerk and then deputy tax collector. A. S. Mann died in 1932 and his wife passed away in 1947. In death, the couple was reunited next to Nellie's grave.

The curtains and toys are long gone, but Nellie's unique playhouse is occasionally painted and re-roofed. Every few years her grave is featured on the Ghosts and Gravestones cemetery tours and the story of little Nellie Mann is shared once again.

by Connie F. Sneed

Edward T. Manton, soldier and writer of an eyewitness account of the Dawson massacre, was born at Johnston, Rhode Island on September 16, 1820.

In 1833, he came to Texas with his brother, Henry, and settled in central Fayette County. In March 1842, when Mexican general Rafael Vásquez attacked San Antonio, Manton joined Rabb's company of Fayette County volunteers and, with them, pursued the retreating Mexican army toward the border. For this service he received a 640-acre bounty grant of land.

In September of the same year, Gen. Adrián Woll again led a Mexican army against San Antonio, and Manton joined Capt. Nicholas Dawson who assembled Fayette County volunteers to help repel the invasion. There were about fifteen men who met and gathered under the historic oak tree in La Grange, where valiant men continued to muster in subsequent wars. The volunteers crossed the Colorado River on a ferry run by a Mr. McAhron, where they were joined by John Bradley and Francis E. Brookfield. The contingent moved along the Old Seguin Road, which stretched from La Grange through Cedar, O'Quinn, Black Jack Springs, Muldoon, Colony, Elm Grove and Waelder on the way to Seguin toward San Antonio.

When Dawson's command was massacred at Salado Creek on September 18, Manton was one of the fifteen prisoners in the Fayette County Company who were taken to Perote Prison in Mexico.

An article in the Houston Telegraph, dated January 25, 1843, states “Survivors of Dawson’s Fayette County Company, all now in Castle of Perote, and in good health on the 31st December, 1842: John Bradley, James Shaw, Edward Manton, Wm. Coltin, Wm. Trimble, David E. Kornegay, Richard Barckley, N.W. Faison, Joel Robinson, Allen H. Morrell. John R. Cunningham died at Leona on the 19th September, 1842.”

At the intercession of Gen. Waddy Thompson, Manton was released on March 23, 1844 and returned to his plantation near La Grange, where he wrote an eye-witness account of the Dawson massacre. In Fayette County, he expanded his holdings by acquiring the John Castleman home at Castleman Springs. He renamed the spring, Manton Spring, and resided near that location until his death on August 20, 1893.

The Dallas Morning News reported on February 3, 1905 that the House Committee on Appropriations adopted a provision on the previous day in Austin, making an appropriation of $3000 for a monument to be erected in La Grange to the memory of Capt. Nicholas M. Dawson and the men under him who fell at the battle of Salado on September 18, 1842, and also to the Mier Prisoners, who drew black beans and were executed on March 23, 1842, after including an amendment by Mr. Terrell of Travis County, that the remains of John Cameron should be removed to La Grange. Appearing before the committee urging the appropriations were Hon. Jake Wolters and Judge Willrich of La Grange; Mrs. Edward Manton, widow of Edward T. Manton, a survivor of Salado and a prisoner at Perote; Judge Sam Webb and Hon. C.E. Lane of Fayette County.

That monument honoring those brave men still stands on the east side of the Fayette County Courthouse.

Edward T. Manton’s correspondence, legal documents and reminiscences are in the Barker Texas History Center, University of Texas at Austin.

By Gary E. McKee

A provision of Stephen F. Austin’s colonization contract with Mexico was that the Roman Catholic religion would be the only one practiced in colonial Texas. This “minor detail” was pretty much ignored by the majority of the Protestant settlers, until it became a legal issue when the subject of marriage came up. There being only one known priest that visited the colony, Father Miguel Muldoon, who spent a lot of time in Mexico. So to keep the colony growing spiritually, morally, and population wise, Austin authorized Marriage Bond ceremonies to be performed between a couple who could not wait the sometimes year or more for the priest to show up to perform a proper Catholic wedding, which was not high on their list of rituals. The following is a Marriage Bond issued in 1824 concerning the offspring of two families of Fayette County colonists. All original punctuation and spelling has been retained.

Marriage Bond

Be it known by these presents that we John Crownover and Nancy Castleman of lawfull age inhabitants of Austin’s Colony in the Province of Texas wishing to unite ourselves in the bonds of matrimony, each of our Parents having given their Consent to our Union, and there being no Catholic Priest in the Colony to perform the Ceremony—therefore I the said John Crownover do agree to take the said Nancy Castleman for my legal and lawfull wife and as such to cherish support and protect her, forsaking all others and keeping myself true and faithfull to her alone, and I the said Nancy Castleman do agree to take the said John Crownover for my legal and lawfull husband and as such to love honor [and] obey him forsaking all others and keeping my [self] true and faithfull to him alone. And we do each of us bind and obligate ourselves to the other under the penalty of ______ Dollars to have our Marriage solemnised by the Priest of this Colony or Some other Priest authorized to do so, as soon as an opportunity offers—All which we do promise in the name of God, and in presence of Stephen F. Austin judge and Political Chief of this Colony and the other witnesses hereto signed

Witness our hands the 29th of April 1824

Witnesses present

Be it known that we Sylvanus Castleman and Elizabeth Castleman the parents of the within named Nancy Castleman do hereby give our consent to the marriage of our said daughter with the within named John Crownover—April 29, 1824. Attest.

Stephen F. Austin then issued a proclamation that he had witnessed the ceremony and it was legal, at least in the eyes of the colonists. It has been noted that more than one Catholic wedding was attended by the children of the bride and groom.

From The Austin Papers, edited by Eugene C. Barker, 1924.

by Carolyn Heinsohn

Two brothers born in Fayette County in the latter half of the 19th century pursued architectural careers that took them from humble origins to being recognized as successful, highly-acclaimed designers of outstanding homes and buildings.

Two brothers born in Fayette County in the latter half of the 19th century pursued architectural careers that took them from humble origins to being recognized as successful, highly-acclaimed designers of outstanding homes and buildings.

Their story begins with the emigration of their grandparents, George H. Mauer, Sr. and wife, Emilie; daughter, Emilie, who died within the first ten years after arrival; and son, George, Jr. Originally from Liegnitz, Silesia, they moved to Oldenburg, Prussia and then immigrated to Texas in 1850 and settled in Fayette County. By 1852, Mauer purchased three tracts of land totaling 169 ½ acres in the Joseph Biegel League from Christian Wertzner, the first permanent German settler in Fayette County, who arrived in 1831. Wertzner, who supposedly influenced Joseph Biegel to select his league in Fayette County, then purchased 1,872 acres from Biegel in 1839 and sold it in parcels to new settlers. A large portion of the Biegel League is now part of the LCRA power plant property or under its cooling lake.

By 1862, George, Jr., age 19, was a private in Co. A, Luckett’s 3rd Regiment, Texas Infantry, CSA. In 1866, he married Sophie Steves, the 20-year old daughter of Siegbert Steves, a cabinetmaker in Fayetteville, and wife, Hendrina Zeuven. The Steves were some of the earliest German settlers in Fayetteville, having emigrated because of the Revolution of 1848 and economic pressures in Germany. Their home is still standing behind the two-story Masonic Lodge building located on the northeast corner of the square in Fayetteville.

In 1877, George Mauer, Sr. purchased an additional 120 acres near Rutersville. He apparently had died by mid-1879, when his wife, Emilie, sold their acreage in the Biegel settlement. After that transaction, Emilie and her son, George, Jr., and his family moved from Biegel to the Rutersville property. At some point, George, Jr. went into the construction business, but continued farming as well. He was also a county commissioner for four years from 1886 to 1890. George, Jr. and Sophie had nine children, two of whom are the subjects of this story.

Louis Mauer, their eldest son born in 1868, became an architect, most likely being influenced to do so by several family acquaintances through marriages, all of whom were well-established businessmen. Louis’ younger sister, Lydia Mauer, had married Leon John Speckels, whose uncle was Henry Speckels, a well-known businessman in La Grange, who also designed and built homes and remodeled building fronts and interiors, including the Hermes Drug Store. Henry’s brothers-in-law were Axel and Paul Meerscheidt. Axel was not only educated as an architect in Heidelburg, Germany, but also studied law and became an attorney, and then a real estate developer. It is quite possible that Axel mentored or assisted Louis with his aspirations to become an architect. Axel’s brother, Paul, was also sent to Germany to be educated. He later received his law degree and joined Axel in the real estate business in San Antonio, where they developed the Meerscheidt Riverside Addition, as well as other early subdivisions.

Louis first worked on his own in La Grange and designed the magnificent H.P. Luckett House, a Queen Anne-style 14-room house with double wraparound galleries and ornately carved interior woodwork. It was built for a local physician in Bastrop, TX in 1893 at the site of the old Bastrop Military Institute. It remains one of Bastrop’s most photogenic historic landmarks. Mauer then partnered with a Mr. Wesling after 1894; their office was located on the second floor in a building on West Colorado Street that was built by Axel Meerscheidt and John Schumacher, a local bank owner. The post office occupied the east half of the first floor of the building from 1894 to 1906. After a jewelry store vacated the other side in 1892, the First National Bank took its place. Eventually, the bank purchased the entire building.

The architectural firm of Mauer and Wesling designed an impressive, innovative two-story brick building that was built in 1895 for Fey and Braunig, photographers, in Hallettsville on the south side of the square. The second floor was used as their photography studio, and a stationery store was housed below. With its unique glass skylights and curved front windows, it was the first building of its kind west of the Mississippi to be used exclusively as a photography studio. Mauer was also a supplier of building materials in La Grange in the 1890s, but that business went bankrupt. He eventually moved to San Francisco, where he worked as an architect and associate editor for an architectural publication, contributing articles on waterproofing methods.

He later moved to New York City, where he had a successful career until he retired. In his earlier years there, he designed a four-story 21-family apartment building in the Bronx and a nine and a half-story store and office building in 1905. Then in 1908, he designed the Hotel on the Hudson in Nyack, NY, followed by a six-story warehouse in New York City in 1909 and a five-story tenement building in 1911. He never married and died in Philadelphia, PA at the age of 81 in 1948.

Louis’ younger brother, Henry Conrad, born in 1873, helped his father in the construction business for about four years after getting his secondary education. Apparently, his brother and other family acquaintances influenced his decision to pursue a career in architecture as well. He may also have had their financial assistance to be able to attend the prestigious Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, NY, where he received his education in architectural design.

Louis’ younger brother, Henry Conrad, born in 1873, helped his father in the construction business for about four years after getting his secondary education. Apparently, his brother and other family acquaintances influenced his decision to pursue a career in architecture as well. He may also have had their financial assistance to be able to attend the prestigious Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, NY, where he received his education in architectural design.

After returning to Texas, Henry Mauer moved to Beaumont, TX, where there was a building boom due to the successful lumber and shipping industries, as well as the wealth generated by the discovery of oil at Spindletop in 1901. He married Kate Adams in Jasper, TX in 1903. They had one son, Henry Conrad, Jr., born in 1907.

Henry’s architectural office was isolated in his home on Spruce Street away from the main avenues of trade and commerce, but he was somehow connected to the movers and shakers of the city to be awarded the commissions for some of the grandest homes in Beaumont. He incorporated local materials with the most advanced electrical, heating and plumbing systems of the time.

His most outstanding design was for the striking and distinctive McFadden-Ward House, a 12,800 square foot, three-story Beaux Arts Colonial Style home built in 1905-1906. Di Vernon Averill commissioned Mauer to build the home; however, she then traded homes with her brother, William H.P. McFaddin, in 1907. He added a large carriage house with a stable, hayloft, garage, gym and servants’ quarters. The Averills had considerable wealth from the cattle business, rice farming and commercial real estate, and McFaddin also owned part interest in the land where oil was discovered at Spindletop.

His most outstanding design was for the striking and distinctive McFadden-Ward House, a 12,800 square foot, three-story Beaux Arts Colonial Style home built in 1905-1906. Di Vernon Averill commissioned Mauer to build the home; however, she then traded homes with her brother, William H.P. McFaddin, in 1907. He added a large carriage house with a stable, hayloft, garage, gym and servants’ quarters. The Averills had considerable wealth from the cattle business, rice farming and commercial real estate, and McFaddin also owned part interest in the land where oil was discovered at Spindletop.

The home was occupied by the same family for 75 years and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1971. It is one of the few house museums in the United States in which the original furnishings are still intact and on display.

Henry Conrad Mauer died at the age of 66 years in Beaumont in 1939. He and his brother, Louis, each left an impressive legacy of architectural accomplishments in three different states, but their story began on a farm in Fayette County. Their determination to succeed could be called “True Grit”!

by Ed Janecka

The coming of electricity is probably the most important event that changed people's lives, especially in rural areas. Electricity not only brought electric lights and water pumps, but also perhaps the most single important appliance, the refrigerator. However, the evolution of refrigeration also brought about the end of meat clubs, also known as beef clubs.

The coming of electricity is probably the most important event that changed people's lives, especially in rural areas. Electricity not only brought electric lights and water pumps, but also perhaps the most single important appliance, the refrigerator. However, the evolution of refrigeration also brought about the end of meat clubs, also known as beef clubs.

A meat club generally consisted of a group of five to seven individuals, but there could be as many as ten in a group. One member of the group was designated to be the butcher. Clubs were organized for the purpose of having fresh meat weekly, and the process was fairly straightforward. Each week one of the club members donated a steer or a heifer to be butchered. The butcher did not have to contribute an animal; his participation in the group was the butchering process. There were occasions when inferior calves were delivered to the butcher. If the same group member continued to deliver inferior calves over a long period of time, then that person was asked to leave the meat club or produce a better steer or heifer.

On butchering day, the person whose turn it was to provide a calf delivered it to the butcher’s location. After the calf was butchered, the meat was divided into as many portions as there were members. If there were seven members in the group, including the butcher, then the calf was divided into seven portions. Each week, a club member received a different part of the calf that he took home in a “meat sack”, generally made of a heavy-duty material.

Butchering was usually done on Friday or Saturday, so that there would be fresh meat for the weekend in case company were to come. If the butchering was done on a Friday, however, it was more challenging for Catholics, who did not eat meat on Friday. Once the meat arrived home from the butcher, some of it may have been prepared for the evening meal, but most of it was fried up and then placed in large containers of lard. Usually, crocks with lids were used for preserving meat in this manner. Lard preserved the meat for a long period of time, because it served as a barrier against bacteria. Oftentimes, the lard-covered meat was stored in a cistern house to keep it cooler. Some individuals would take a portion of their meat, wrap it up and place it in a bucket down into the water well to keep it cool for a day or two.

The entire process changed with the coming of electricity and refrigeration. Most people then butchered their own calf at home. Once the calf was butchered, the meat was wrapped and placed in the freezer compartment of the refrigerator. Because of limited freezer space, most people butchered a calf with their relatives and then divided the meat. Just think how wonderful it was for people to have meat every single day of the week throughout the year.

by Sherie Knape

The Fayette County Medical Society was formed in 1874. Although the meetings were held in La Grange all doctors of Fayette County were invited to join including general doctors as well as surgeons, dentists and other specialty doctors.

The society met annually to compare notes, give an account of their experiences during the year and discuss matters beneficial to both themselves and their patients.

Though the membership of the society was not large it was composed of gentleman who stood high in their professions and who took great interest and pride in promoting its usefulness. Many well-known doctors of Fayette County were members of this society. Some of the more prominent members included W. W. Lunn, J. C. B. Renfro, R. A. McKinney, F. E. Young, J. K. Gault, J. T. Carter, J. W. Smith and C. E. Kellar.

Just as many patients question the fees of medical doctors and hospitals today, many in the community thought that the society was formed for the purpose of fixing the fees of the physicians in the county. But the society members firmly stated that the group was formed merely to enhance communication and cooperation among the different physicians, which in the end would help patient care in the county.