Flatonia Footprints of Fayette Articles

FAYETTE COUNTY, TEXAS

These brief histories were written by members of the Fayette County Historical Commission. They first appeared in the weekly column, "Footprints of Fayette," which is published in the Fayette County Record, Banner Press, Flatonia Argus, Schulenburg Sticker, and Weimar Mercury newspapers. A new article appears weekly. See index of all Footprints of Fayette articles.

Old Flatonia

By Judy Pate

“The road widened to allow for a blacksmith shop with hitching rack along the front, a general mercantile store, with porch and boardwalk leading to the next, a butcher shop, a saloon and a barber shop. Across the road a second general store with a drug store railed off in the rear just about made up the business district of the town of Flatonia, Texas, in the eighteen fifties and early sixties. Each place of business had its hitching rack. Town pump and water trough sat back from the road in a vacant lot. Probably two dozen residences were scattered on both sides of the road. The store with drugs also housed the post office. This briefly was Flatonia, Texas.” (From G. P. Reagan, Country Doctor by Rocky Reagan)

“The road widened to allow for a blacksmith shop with hitching rack along the front, a general mercantile store, with porch and boardwalk leading to the next, a butcher shop, a saloon and a barber shop. Across the road a second general store with a drug store railed off in the rear just about made up the business district of the town of Flatonia, Texas, in the eighteen fifties and early sixties. Each place of business had its hitching rack. Town pump and water trough sat back from the road in a vacant lot. Probably two dozen residences were scattered on both sides of the road. The store with drugs also housed the post office. This briefly was Flatonia, Texas.” (From G. P. Reagan, Country Doctor by Rocky Reagan)

The community now known as “old” Flatonia was located on the George W. Cottle League in southern Fayette County. While this area was most likely first settled in the 1850s by people moving from the southeastern states, it attracted a fair number of German immigrants in the 1860s and among these latter was merchant F. W. Flato. Flato had left a life at sea in1846 to put down roots in Texas, settling first in New Ulm in Austin County, then moving his growing family to High Hill and finally in 1866 to this fledgling colony which soon came to bear his name.

By 1870 the population had increased enough in this far corner of southwest Fayette County to warrant the establishment of its own post office. The census that year shows about 475 inhabitants for the total postal area. Village commerce was carried on by 4 merchants, 2 blacksmiths, 3 carpenters, 3 physicians, 1 shoemaker, 2 wagon makers, 1 land agent, 1 grocer, 1 saddler, 5 clerks, 2 teamsters, 1 miller and 2 mill hands. Responsibility for education lay in the hands of a single teacher. Farmers, ranchers, field hands and share croppers, along with their wives and children, made up most of the remainder of the population in the surrounding area.

The inhabitants of Flatonia were not entirely isolated, however, as trade and other forms of contact linked Flatonia with other communities in the county. Mrs. Lucy Sullivan of Oso, a small village located about 6 miles to the northeast, noted several trips to Flatonia in her journal from 1869 through 1871. The merchandise in its stores must have been attractive: her daughter America bought a hat there on Christmas Day, 1869; in April her husband returned from a day’s trip to Flatonia with 20 gallons of molasses, 40 lbs. of apples and 8 lbs. of soap; in June he paid $3.75 for a “fine dress” for another daughter, Bettie. Mrs. Sullivan also wrote that her husband attended a trial there in February, 1870, and in March of 1871, she commented that several Germans from Flatonia attended the funeral of an Oso neighbor by the name of Abe Penn.

In 1873 the Galveston, Harrisburg & San Antonio Railway began construction of its new line which passed about two miles northwest of the existing community. F. W. Flato and two other local entrepreneurs—John Cline and John Lattimer—brokered the deal between the railroad company and land owner William A. Faires for the site on which the new town of Flatonia was platted. When the tracks were completed to this point and the first train arrived in April of 1874, the inhabitants of “old” Flatonia soon began to move their homes and businesses to be near the depot and what would become the new center of commerce for the area. The post office also moved to the new town site in 1874, taking with it its name. The new city was incorporated as Flatonia in 1875, and eventually all that was left to remind us of the town’s birthplace was its graveyard.

Photo: Grave of Wilhelm Koch (1809-1878) in the Old Flatonia Cemetery. Photo courtesy of Judy Pate

Mai Fest at Flatonia in 1877

By Judy Pate

The celebration of the Mai Fest has long been a tradition among German immigrants in Texas. The first to be held in Flatonia came a mere three years after the first train arrived in the town and less than two years after it incorporated. By that time, the original location of the town was already being called “Old Flatonia”, while Praha was still known as “New Prague”.

The following is a transcription of an article which appeared in the Galveston Daily News on May 2, 1877, sent by special telegram and subtitled a “Fine Celebration of a Thrifty German Community in the Interior”:

“FLATONIA, May 1, 1877. The Germans of Flatonia and vicinity held their first Mai Fest to-day at the school house at Old Flatonia, two miles from town. The morning opened bright, and at an early hour the farmers and citizens from the surrounding country began to pour in, so that by nine o’clock the town was full of men, women and children. The procession was formed by the Marshal, A. Linkilstein of Flatonia, and C. Brunnel of New Prague and, marched through the principal streets, headed by the High Hill brass band. They then marched to New Prague and from thence to the school-house, where the day and night were spent in true German style.

The procession was one and a half mile long. The first car contained emigrants coming to Texas. This car represented Germans with families and baggage checked to Flatonia, and drawn by four yoke of oxen.

The second car represented ten years later, drawn by mules. This car was fitted up with a parlor-set of black walnut furniture, and was intended to show the progress they made in ten years. It carried an elegant family.

The third car represented mechanics at work. It contained blacksmiths, tinsmiths, carpenters, painters, harness-makers, shoemakers and barbers.

The fourth car represented the City Market, and it contained beef, vegetables, bread and cake.

The sixth car contained the Queen, Miss Eda Koek. This car was most gorgeously fitted up, and the maids of honor surrounded the Queen.

The seventh car contained the old and the new way. The old way, in front, was loaded with lager beer, wines, etc., and the new, cold water drawn from a new well on the car.

The eighth car was loaded with Flatonia school children and teachers.

The ninth car was full of little boys, and was tastefully decorated.

The tenth car was drawn by three teams nicely decorated, and contained the school children of New Prague.

After this came citizens in carriages, wagons and on horseback. They reached the grounds at 1 P. M, where dinner was awaiting them. After dinner Miss Eda Koek, of New Prague, was introduced and crowned. After the coronation, all took part in tripping the light fantastic toe until a late hour. All the wagons were decorated with the German and American flags.”

Transcriber’s note: In the first paragraph of the text, Linkilstein is probably meant to be Finkenstein and Brunnel meant to be Brunner.

An Electric and Ice Plant for Flatonia

Transcribed by Connie F. Sneed

August 15th, 1910 - Beaumont Enterprise and Journal Newspaper

Special to The Enterprise - College Station, Texas. Aug 14, 1910

Having faith in investments in Texas towns, a number of the members of the faculty of the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas have associated together and with a practical man from Mississippi to put in an ice plant at Flatonia, Texas.

Flatonia has neither ice nor electric light plant. There was an electric light plant there at one time, but it was destroyed by fire. The town is a thriving one in Fayette County and it appeared to the investor as a proper place in which to locate. T.M. Spinks, who has been assistant professor of mechanical engineering at the A&M College of Mississippi, at Starkville, has resigned his position and is to come to Texas to take charge of the property. Associated with him are Professor F.C. Roitan, professor of electrical engineering and Dr. J. C. Blake, professor of Chemistry of the A&M College of Texas. They have a fifty year franchise at Flatonia and will invest between ten and fifteen thousand dollars in this plant. It is proposed to have the light plant in operation by October.

1910 was a busy year for the Flatonia community. A new electric light plant, ice plant, water works, cold storage, creamery, and sauerkraut packing plant kept this area thriving with businesses.

In 1924, The Beaumont Enterprise and Journal reported that the Flatonia Ice and Electric Light Company had secured a franchise to furnish light for Waelder, twelve miles from Flatonia. A high tension line will be installed and new machinery added to the plant, which at present is one of the best in the section.

The Flatonia Fair, 1913 - 1936

By Judy Pate

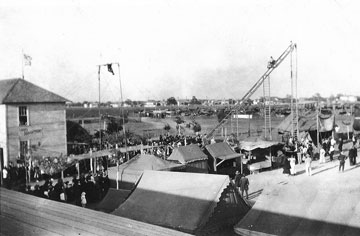

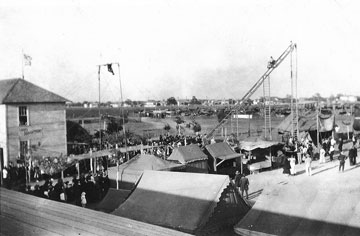

The Flatonia Fair in its Glory Days—The “Twirl of Terror”.

Photo courtesy E. A. Arnim Archives & Museum.

|

The Giggle Path. Spidora—the spider with a girl’s head. The Twirl of Terror—sensational Smithson cycling the chasm. The Baby Show with prizes for the most beautiful baby and the heaviest baby. Parades, speakers, ballgames, goat-roping, horse races, fireworks, old fiddlers contests, and grand balls nightly—just a few of the numerous attractions to be found over the years at the Flatonia Fair.

The idea that ultimately grew into a full-fledged fair was first born of a desire among the members of the Flatonia Herman Sons Lodge to create a public park. In July of 1912, fifty-four of the club’s members organized under a separate charter as the Hermann Sohns Park Verein (Herman Sons Park Association). Capital was raised through an initial stock offering of 200 shares at $10 each, with which the board of directors promptly purchased six acres for the park in the western part of Flatonia.

Next they set out to build a permanent multi-purpose hall on the park grounds. Over the years, a spacious two-story building would serve not only as the main fair exhibit hall, but as the site of countless meetings, picnics, dances, basketball games, graduation exercises and plays. If at first there were rumors that only members of the Herman Sons lodge would be permitted to use the facilities, they were quickly laid to rest as it was stressed that the park was meant for the enjoyment of the entire community.

Following a grand opening of the park in May of 1913, the stage was set for an extravagant 4th of July celebration that summer. This was dubbed Flatonia’s first “fair”, but by 1914 it became a fair indeed. Attended by none other than the current Texas Governor, the Honorable O. B. Colquist, the fair ran for four action-packed days and nights under the name of the “South Texas Industrial and Agricultural Fair.” By 1916 it had become simply “The Flatonia Fair” which continued to grow and add events for the next 20 years.

Of course there was always a full range of agricultural and industrial exhibits. Not only were there the usual calves, chickens, ducks, geese and hogs, there were prizes for best collie dog, “possum”, wolf and fox. The ladies were busy competing in divisions for best canned and baked goods, needlework, fine arts, and floral arrangements. For children there were prizes for best water colors, crayon drawings and penmanship.

Ball games were a perennial favorite with the crowds. The very first year, The Flatonia Argus reported that the baseball field was in poor condition, as it had only recently been scraped out of a pea pasture, and although Flatonia lost to Shiner it was said that the errors “couldn’t be blamed directly to this cause.” By the following year the baseball field had been improved, a grandstand built, and games were played daily. There were about 400 fans present for the final match between Schulenburg and Flatonia when “the visitors showed a disposition to squabble at every unfavorable decision”—but Schulenburg still won the game. As the dates shifted from mid-summer to September and October, football and basketball sometimes replaced baseball as the game of choice.

Railway fares were reduced within a 75 mile radius of Flatonia for the duration of the fair and it was well-attended by people from all over the region. Special days were designated, like “Old Settlers Day”, “German Day” and “Bohemian Day”. In 1914 one day was declared to be “Automobile Day” and various speakers addressed the crowds on such things as “Good Roads—Why and How,” “The Moral Effect of Good Roads,” and “Why We Must be Progressive.”

As the Great War raged in Europe, the 1916 fair opened with a patriotic red, white and blue parade through the town. An aviator wowed the crowds with his sensational “bird man” performances, looping the loop and flying upside down.

By 1918 the United States was well into its own share of the fight in the Great War and Flatonia dubbed its fair that year the “Liberty Fair”. Booth space was donated to the Red Cross and the 4th Liberty Loan, whereby an additional $250 was raised over the course of the fair. Ellington and Kelly Fields supplied a number of airplanes to perform “miraculous maneuvers” over the fairgrounds which managed to bring one of the ballgames to a halt as one flew directly over the playing field.

Aerial View of the Flatonia Fair, circa 1919. Herman Sons Hall top, center. Photo by Walter Wotipka, Sr., courtesy E. A. Arnim Archives & Museum.

|

Closing out the decade, 1919 brought the “Victory Fair” as Americans celebrated the end of the war. Opening ceremonies included an address on “the greatest issue before the American people today—the Peace Treaty, including the League of Nations Covenant.” Military bands provided the daily concerts. In the “old relics” division of competition, the usual contest for the best collection of Indian arrows was replaced by that for the best collection of war relics from France.

The Flatonia Fair continued to gain momentum through the 1920’s. Spectacular fireworks displays became a nightly feature. There were programs to honor old soldiers with Confederate Veterans Day and newly returned soldiers with American Legion Day. In 1923, air planes offered daily pleasure rides from the fair grounds. Radio concerts were broadcast in the main exhibit hall—“news of the world daily at the fair—everything that happens at the time when it happens.”

Even as the fair continued to grow, however, the seeds of its demise were already being sown. With misplaced confidence in the viability of the fair and unaware of the hard times ahead, the directors of the Fair Association took out sizeable loans to construct new permanent exhibit halls in the mid-1920s. As the economy was beginning its long slide into the Great Depression, money was suddenly in short supply everywhere. One attempt to raise money through an additional stock offering and another to sell its property to the City of Flatonia both met with failure. Attendance was down in 1935—no doubt potential fair-goers were feeling the pinch in their own pocketbooks. With the prevailing sentiment of “the show must go on,” the Centennial Fair of 1936 was held, but with bad luck continuing to pile on, two of the four days were rained out.

Though many still fondly hoped to celebrate the Silver Anniversary of the Flatonia Fair in 1937, the handwriting was on the wall. When the books were closed on the 1936 fair, expenditures had exceeded proceeds and the directors of the Fair Association concluded that they could not repay $8000 worth of loans and debts in the prevailing economic conditions. On March 5, 1937, all assets, including land and buildings, of the Fair Park were conveyed to its creditors. In short, the Association was bankrupt and the Flatonia Fair was no more.

The [Flatonia] Train Robbery

By Eugenia Reeves

Excerpts taken from the Gonzales Inquirer, June 25, 1887:

Last week Friday night, between 12:00 and 1:00 o‘clock, a train robbery was perpetrated on the east bound passenger train a mile and a half from Flatonia, Texas.

Two men boarded the engine as the train started from Flatonia. The engineer started to kick them off thinking they were tramps, but at the muzzle of two drawn pistols, he was quickly convinced he had made a mistake. They made him put on extra steam and stop over a trestle about a mile and a half east of Flatonia. Earlier, ten other robbers built a large fire next to the track and boarded and quickly went to work. The express messenger was hit on the head and robbed of $600.00. He secretly hid the bulk of the money before they reached him. The robbers went through the sleeper cars taking $600.00 in money and $1,000.00 in valuables and jewelry from the passengers.

After leaving the train, they mounted their horses and rode off in different directions. Posses were formed, but only three arrests were made and taken to Flatonia for identification. George Shoaf, a noted San Antonio gambler, was one of the bandits who helped in the robbery. He was arrested in San Antonio and jailed. Shoaf denied his connection with the robbery and said he could prove that he was playing poker in San Antonio.

Wells Fargo & Co. offered $1,000.00 reward for the capture and conviction of each one of the robbers. Upon the request from the Express Company, the Governor promised the State’s power to capture the robbers and added $500.00 for the capture and conviction of each of the robbers. The Southern Pacific Railroad also offered $250.00, and the United States Government added another $200.00 which totaled $1,950.00.

After reading the above article, Mike Buck from Giddings, TX added this very interesting bit of information.

The leader of the outlaw gang that committed the train robbery was my great-great grandfather Bill Whitley. He and Brock Cornett boarded the train and then forced the engineer to stop on the trestle."

The San Antonio Express and Houston Daily Post published articles in 1887 issues on the robbers, listing passengers and money and valuables taken. Mr. Buck’s great-great grandfather, Bill Whitley, also robbed a train at McNeil (Round Rock) prior to Flatonia, then went on to rob the First National Bank of Cisco and finally a train at Harwood (close to Gonzales and Waelder). He was later killed at Floresville by six U. S. Marshals after the Harwood hold-up.

Mr. Buck has his pistol, passed down to him by his grandfather, which was used in all of the robberies. Bill Whitley was only 24 years old at the end of his short career, which was typical of most outlaws of the Old West.

Credits go to The Gonzales Inquirer, Lone Star Diary and Mike Buck.

Flatonia Train Robbery of 1887

by Fayette County Judge’s Staff

Taken from the Dallas Morning News on June 19th, 1887:

Schulenburg, Tex. June 18. – When the east bound Southern Pacific passenger train, due here at 1:03 o’clock this morning, arrived nearly an hour behind time, the engineer gave four long, loud whistles, indicating an alarm or distress. The town marshal and a few other citizens were soon at the depot and learned that the train had been robbed. B. A. Pickens, engineer, stated that upon leaving the depot at Flatonia he saw a man whom he took for a tramp or drunkard crawling up on the tender. Rickers asked him to state his business, whereupon the man arose, presented a pistol at the engineer and told him to be quiet and stop the train when commanded to do so, and then called Dick, an accomplice, who was concealed between the tender and express car. The engineer was told to stop the train . . .

Also taken from the Dallas Morning News on June 19th, 1887, but titled “Account From Nearer the Scene”:

Flatonia, Tex. June 18. – When the 12:30 a.m. train pulled out last night a man alone boarded the train and soon after advanced to the engine. When about two miles east of town, while running over a high trestle, he saw a fire on the track ahead, which was a signal to stop. He ordered the engineer at the muzzle of a pistol to stop the train, which was readily complied with, and immediately six others appeared on the scene and began the usual maneuvering preparatory to a train robbery. Part were assigned to the mail and express cars while the others paid their attention to the passengers. In the meantime Express Messenger Folger had locked his safe, and upon being ordered to shell out his funds, handed over $600, the remainder being in the safe, which he positively refused to open, though being repeatedly beaten over the head with a pistol, amid threats of instant death. The amount in the safe has not been learned. The robbers went through all the cars and called on all the passengers, there being quite a number, to contribute their cash promptly.

Note the difference in the two stories on the event that happened on the same day.

This article pertains to the capture of the train robbers involved in the Flatonia Train Robbery. It is taken from the Dallas Morning News on September 14th, 1887:

Meridian, Tex., Sept. 13. – The parties, Tom Jones and Jim Menson, who are alleged to have lured the two youths of Valley Mills into illicit dealings in horse flesh in July, and who were arrested on the Colorado River in San Saba County for theft of horses in this county, an account of which was published in The News at the time, are alleged to be members of the McNeil and Flatonia train robbery gang, the former it is charged, participating in the Flatonia robbery, the latter, it is said, in both. The clue was discovered by overhearing a conversation between them in jail. Henson, who has turned State’s evidence in several instances on charges of stage robbery already, when charged with complicity in the train robberies by Sheriff Metcalf admitted the fact and agreed to give the whole gang away and produce the evidence to convict them providing the officers would see to it that he got off as light as possible. Deputy United States Marshal Bailes of San Antonio was here Sept. 7, at the instance of Sheriff Metcalf. The arrest of John Crisswell last Saturday was one of the results of his visit here. Others will soon follow. Jones and Menson will be removed to San Antonio Sept. 23.

The last article is taken from the Dallas Weekly Herald on October 1st, 1887. It concludes our story that followed the Flatonia train robbery.

Train Robbers on Trial. Testimony Which Will Bring All the Gang to Justice.

Austin, Tex. Sept. 27.—To-day was set for the trial of the alleged train robbers arrested at San Antonio and at 10 o’clock they were arraigned before United States Commissioner Ruggles, District Attorney Kelborg representing the government. One of the men, Humphreys, at the outset turned state’s evidence and gave away the whole business of the train robbing alleging, however, that he was employed by the gang to drive a wagon and that he took no active part in the robbery. He told a good many things but the ends of justice require that no publication be made. Tom Jones, another of the men, took the stand and plead guilty to being in the Flatonia Robbery. John Cresswell and John Brown, two others of the crowd, are on trial this afternoon. The events to-day point to a disclosure of the inside workings of the train robber gang and it is possible it will lead to bringing all the members to justice.

The Great Train Heist at Flatonia in 1887

by Brendan Steinhauser

The gang of train robbers met at night in the Flatonia graveyard on June 15, 1887. Around the campfire they plotted the details of their next move: robbing a train about a mile and a half east of Flatonia near Mulberry Creek. The robbery would make international headlines, would secure the notorious gang’s place in Texas history, and would make the town of Flatonia known as the site of “the most daring robbery ever in Texas,” as the New York Sun described it.[1]

The gang of train robbers met at night in the Flatonia graveyard on June 15, 1887. Around the campfire they plotted the details of their next move: robbing a train about a mile and a half east of Flatonia near Mulberry Creek. The robbery would make international headlines, would secure the notorious gang’s place in Texas history, and would make the town of Flatonia known as the site of “the most daring robbery ever in Texas,” as the New York Sun described it.[1]

On the evening of June 18th, the Cornett-Whitley gang, as they were known, waited until about midnight before they made their move. The leaders, Braxton “Brack” Cornett and George Whitley, boarded Southern Pacific train No. 19 at the Flatonia train station on the Sunset Line, and posed as passengers. About a mile and a half east of Flatonia, three or more other gang members were waiting at the designated spot on a bridge over the creek. They kept warm by the fire and watched out for the train as it made its way down the tracks. The passengers, conductor, and engineer did not anticipate what was about to happen.[2]

Suddenly, Cornett and Whitley drew their pistols on the engineer Ben Pickren, and told him to stop the train immediately, which he did. The conductor, Jesse Lyons, asked Pickren why he had stopped the train, to which Pickren replied that outlaws were on board and had given the command to halt the train.[3] The rest of the gang, likely three other men, jumped onto the train and assisted with the robbery in progress. As historian David Johnson, author of The Cornett-Whitley Gang: Violence Unleashed in Texas, describes the next scene on the train that night, “The gang demonstrated a vicious cruelty that had not been seen in train robberies. They moved through the train with promiscuous, pitiless violence, as uncalled-for as it was inhumane.”[4] The gang forced the crew to the express car where they encountered Wells Fargo’s Frank Folger, who resisted the robbers and tried to prevent the theft of the train’s safe. In response, they severely beat him with their pistols and cut his ears with pocketknives, leaving him for dead. The gang took the money from the safe, rifled through the mail, and moved on to the passenger cars. There were about fifty passengers on the train that night, from all over the country. Reports indicate that nearly all of them received a beating of some kind, whether with fists or pistols. The passengers were brutalized, robbed, humiliated, and terrified.[5] They murmured among themselves about what could be done, including hiding their valuables and thwarting the robbers. One passenger aboard train No. 19 was Colonel Quintos of the Mexican Army, along with his lieutenant, a man named Cruz. Quintos quietly ordered Cruz to retrieve his pistols so that he could meet the robbers’ violence with his own. But Barbara White, the Spanish-speaking wife of El Paso Sheriff James White, “frantically begged him” not to do so.[6] So the Colonel acquiesced in her pleas and handed over his money. The gang made its way through the train, stealing money and valuables from almost all of the passengers.

Suddenly, John Barber, one of the robbers, announced to the gang that it was time to go, and so they did, leaving behind a path of torment and fear. The robbers made off with somewhere between $7000-$10,000, and escaped to their designated meeting place to divide their loot, a place called Butler’s pasture in Karnes County. The train, with its distressed passengers in tow, then made its way on toward Schulenburg, where the passengers recounted their story and received medical care. Telegrams were drafted and sent in all directions from Schulenburg, and the word spread rapidly throughout Texas, the United States, and even the world. At about 3:20am on June 19th, just a couple of hours after the robbery, the news had made it to Flatonia from a westbound train, where Constable Sloan was on duty. He formed a posse with Constable Hall of Waelder and the manhunt began.

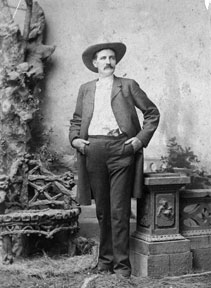

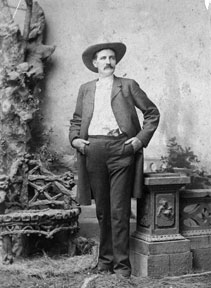

The lawmen rode toward the scene of the crime, but the gang had disappeared immediately after the robbery. The constables did find remnants of the campfire that marked the spot where the train was stopped, as well as horse tracks that indicated that the gang had scattered in different directions. [7] They returned to Flatonia around eight o’clock in the morning and reported their findings. Lawmen from all over Texas were being activated, including Fayette County Sheriff Brutus Lytt Zapp, from La Grange. Zapp had been city marshal of Round Top, and a deputy to former Fayette County Sheriff John Rankin, who was then serving as U.S. Marshal in San Antonio. Zapp began his investigation, speaking to witnesses and arresting suspects, whom he interrogated. Newspapers covered the investigation and arrests, but the real culprits would evade capture for some time.

The lawmen rode toward the scene of the crime, but the gang had disappeared immediately after the robbery. The constables did find remnants of the campfire that marked the spot where the train was stopped, as well as horse tracks that indicated that the gang had scattered in different directions. [7] They returned to Flatonia around eight o’clock in the morning and reported their findings. Lawmen from all over Texas were being activated, including Fayette County Sheriff Brutus Lytt Zapp, from La Grange. Zapp had been city marshal of Round Top, and a deputy to former Fayette County Sheriff John Rankin, who was then serving as U.S. Marshal in San Antonio. Zapp began his investigation, speaking to witnesses and arresting suspects, whom he interrogated. Newspapers covered the investigation and arrests, but the real culprits would evade capture for some time.

The state of Texas, Wells Fargo, and other entities announced cash rewards for information leading to the capture of the robbers. Criminal intelligence began flowing into local sheriff’s offices, the Texas Rangers, and to the U.S. Marshal in San Antonio, John Rankin. There were a number of close calls, including a shootout in Cuero between one of the robbers, John Barber, and the local Sheriff. Barber survived the fight, stole a horse, and escaped. Two of the other gang members, Ike Cloud and Sion Secrest, fled the state. Whitley and Cornett split up and continued their life of crime, even attempting to rob more trains. In Galveston, months later, Whitley and Barber got into a gunfight with local lawmen, were arrested, and then released. But one by one the criminals would be tracked down, apprehended, or killed.

Sheriff Zapp and his deputy got wind that Secrest was being held on a murder charge in New Mexico, and so they traveled to the town of Magdalena to bring him back to stand trial for the Flatonia train robbery. Zapp had received some intelligence from an old detective in El Paso County who had been working the Flatonia robbery case, and he indicated to Zapp that Secrest was one of the Flatonia train robbers. So Zapp, wanting justice for the railroad, the passengers, and Fayette County, retrieved Secrest and brought him back to La Grange to stand trial.[8]

Justice finally caught up with Brack Cornett in February, 1888 when he showed up at the residence of Frio County deputy Sheriff Alfred Allee. The stories differ, but it is believed that Cornett camped out at Allee’s place one night, and the next morning joined him for breakfast. At some point that morning Allee told Cornett that he intended to arrest the outlaw. Guns were drawn, and Cornett shot Allee through his hat, while Allee delivered the fatal bullets into Cornett’s chest and neck. When the smoke had cleared, Cornett was dead, and Allee was eligible for a big cash reward.[9]

There are questions about whether Allee was merely doing his duty as a lawman, or whether he was initially in cahoots with the gang, and merely turned on them to collect his reward. Some people, including descendants of Cornett, allege that Allee was involved with Cornett in the criminal enterprise of horse theft.[10] It is of course possible that Allee was a lawman doing his duty, acting as an agent of law enforcement who rode with the gang from time to time so that he could eventually help bring them to justice. But it is also possible that Allee was acting in his own self-interest, and was a compatriot of the gang until it suited his financial interests to betray them, kill their leader, and collect his $3000 award. This may remain a classic case of competing claims and stories, lacking conclusive evidence one way or another, where the reader must decide for themselves what to believe.

In September, 1888 George Whitley brazenly attempted another train robbery in Harwood, in Gonzales County. But this time, law enforcement officers were ready for him. According to historian David Johnson, it is likely that Eli Harrell, one of his criminal associates, betrayed Whitley to the authorities.[11] The train targeted by Whitley was carrying U.S. Marshal John Rankin, nine deputies, and a Southern Pacific detective. As Whitley and his men attempted to rob the train, shots were exchanged between the gang and the lawmen, and a few of the men were injured. Once Whitley knew that the robbery was going to fail, he called it off and escaped with his men. The lawmen had prevented another train robbery, but they had to continue their manhunt.

Marshal Rankin and his men made their way to the Harrell brothers’ house in Floresville, in Wilson County, where Whitley headed after the attempted Harwood heist. The lawmen waited in the dark house for Will Harrell and Whitley to arrive. When the two men entered the house, Rankin pointed his shotgun at Whitley and demanded his surrender. Whitley responded by firing at Rankin, but missed. Rankin blasted Whitley in the head, ending his career of crime, and his life.[12] Whitley’s descendants disputed this version of events, saying that Rankin executed Whitley without warning, shooting him in the back of the head. Once again, the reader will have to imagine which is the more likely scenario, and may never know for certain.

One by one, the rest of the gang met their demise. Ike Cloud was convicted of larceny and sentenced to three years in Arkansas. Ed Reeves was convicted of the Flatonia and McNeil station train robberies and sentenced to life in prison. Will Harrell was arrested in Floresville on a count of train robbery. Bud Powell hid out in Montana for years until he was finally arrested there in 1892. He served five years in prison, and died in Medina County, Texas in 1936. Sion Secrest stood trial in La Grange, likely in 1889, but the case was dropped due to a lack of witnesses. He met his end while crossing the Llano river, drowning under the weight of his ammunition.[13] In December, 1889 deputy U.S. Marshals met up with John Barber in northeast Oklahoma. Barber opened fire, but received a hail of bullets himself, meeting the same fate that his compatriots Cornett and Whitley had met. The Cornett-Whitley gang would no longer terrorize Texas, and the perpetrators of the violence at Flatonia would finally be brought to justice.

The lawmen who tracked down, arrested, or killed the gang members, were not immune to the wanton violence of the era. Alfred Allee, the deputy Sheriff of Frio County who gunned down Cornett, started drinking heavily and killed more men. He claimed to be haunted by ghosts, including that of Cornett. Allee was arrested in Starr County, in Laredo, in 1896. While out on bail he started threatening people and city marshal Joseph Barthelow stabbed him to death in Reiwald’s Saloon. Barthelow was acquitted and would go on to be a Deputy U.S. Marshal and a Starr County Commissioner.[14] John Rankin, the man who brought George Whitley to justice with a shotgun blast to the head, also met a tragic fate. In November, 1897 he was walking unarmed in Austin when a police officer shot him four times, killing him. Reports suggest that the killing was due to either local politics or a personal dispute of some kind. Rankin’s killer was acquitted of the crime.[15] The U.S. Marshal and former Fayette County Sheriff would be remembered for his deeds in life, and for the nature of his tragic death.

The Flatonia train robbery of June 18, 1887 was one of many train robberies in the post-Civil War era; the era of the railroads, renegade gangs, and gunslingers. While names like Jesse James, John Wesley Hardin, and Sam Bass are quite familiar, the Cornett-Whitley gang is less well-known in the annals of Texas history. But it terrorized citizens, frustrated the railroads, and kept law enforcement officers busy all over the state. The train heist at Flatonia made international headlines, sparked a massive manhunt, and put pressure on local and state officials to do something to put a stop to train robberies, and to bring the gang to justice. Unfortunately, surviving editions of the Flatonia Argus from that era are virtually nonexistent, so we may be missing some pertinent details of the robbery and its aftermath. But thanks to various books, newspaper articles, letters, and other historical documents, historians can piece together what happened, who was involved, and how the gang was finally dismantled.

One source in particular is vital to this research, David Johnson’s The Cornett-Whitley Gang: Violence Unleashed in Texas. Johnson’s painstaking research and writing have brought this otherwise little-known story to light, as well as the historical context of the train robbery at Flatonia. The author sifted through many newspaper articles that had information that turned out to be incorrect, and he did a masterful job of finding well-documented facts to set the record straight when possible. Historical research is an ongoing process, and every discovery raises more questions and inspires new ideas on how to discover, or re-discover, the past.

Photos

Top: North Main St. Flatonia circa 1890s, courtesy of Judy Pate and the E. A. Arnim Museum

Bottom:

Sheriff B. L. Zapp, courtesy of the Fayette Heritage Museum and Archives

Sources

1 David Johnson, The Cornett-Whitley Gang: Violence Unleashed in Texas (Denton: UNT Press, 2019), 83.

2 Author Unknown, “All Hands Up: The Order of the Train Robbers Promptly Obeyed,” Houston Daily Post, June 19, 1887.

3 Johnson, The Cornett-Whitley Gang, 71.

4 Johnson, The Cornett-Whitley Gang, 72.

5 Johnson, The Cornett-Whitley Gang, 73.

6 Johnson, The Cornett-Whitley Gang, 78.

7 Johnson, The Cornett-Whitley Gang, 87.

8 Johnson, The Cornett-Whitley Gang, 149-150.

9 Author Unknown, “He Will Rob No More: A Bad, Bold Highwayman Shot to Death – ‘Captain Dick’, Leader of the Flatonia Train Robbers, Killed by Deputy Sheriff A.Y. Allee – Something of the Bandit’s Career,” San Antonio Express, February 14, 1888.

10 Johnson, The Cornett-Whitley Gang, 141.

11 Johnson, The Cornett-Whitley Gang, 166.

12 Johnson, The Cornett-Whitley Gang, 172.

13 Johnson, The Cornett-Whitley Gang, 190.

14 Johnson, The Cornett-Whitley Gang, 195.

15 Johnson, The Cornett-Whitley Gang, 196.

A Texas-Montana Romance [for one of the Flatonia Train Robbers]

by Connie F. Sneed

From the Tacoma Daily News, page 7, 24 Feb 1893:

She Loves Her Lover, Though He Is A Train Robber

He reformed, is now a model prisoner, and she will wed him when his term expires.

San Antonio, Tex., Feb. 23 - Bud Powell, alias Charles Thompson, who pleaded guilty before Judge Maxey of the Federal Court at Austin yesterday to the charge of train robbery, has been confined in jail here during the past six months.

He, with five others of the most desperate men of Southwest Texas, held up a Southern pacific train near Flatonia, east of here, in 1887, robbing the Wells-Fargo Express of $35,000, besides securing a large amount of money and valuables from the passengers. Four of the robbers have since been killed while resisting arrest.

The only one of them yet sentenced for the crime is “Bill” Reeves, who is serving a life sentence in the Detroit penitentiary. Powell proceeded immediately to Montana after the robbery, gambling all of his ill-gotten wealth away on the journey. Arriving at Helena, he determined to better his ways. He entered a business college there, from which he was graduated with honors. He then joined the church and became an active religious worker.

Three years ago, he became superintendent of an extensive ranch near Border City, Montana. He went under the name of Charles Thompson and was the accepted suitor of the daughter of the owner of the ranch of which he was superintendent. A few days before the date of his proposed marriage, United States Marshall Frick got on his trail and arrested him. That was six months ago.

Powell has been a model prisoner since his confinement here and says he is determined to lead a Christian life. The wealthy ranchman’s daughter to whom he is betrothed has remained true to the prisoner, and they have corresponded regularly. They are to be married as soon as Powell’s term in the penitentiary is completed. Sentence is to be passed on the prisoner next Saturday. It is expected he will get off easy.

Unraveling the Mystery of Flatonia’s Elephant

by Judy Pate

“The Great Campbell Bros. Circus held forth here last Wednesday and enjoyed a liberal patronage. This show was the largest seen here in several years . . . This show had the misfortune to lose an elephant at this point, dying just before arriving in Flatonia”. So goes a short report in The Flatonia Argus of November 30, 1911, the discovery of which began to shed new light on what had long been an unsolved mystery.

It was exactly 100 years ago this month that the story began as the huge Campbell Bros. Circus rolled into town on railcars and made preparations for two scheduled performances in Flatonia on November 22nd. A circus provided exciting entertainment in those days and there’s no doubt that the death of one of its elephants would be big news in a small town. Though the exact details were all but lost in the sands of time, the memory of the event lingered in the communal consciousness in some form or fashion in all the intervening years since. That it was buried somewhere in Flatonia seems to be the only point on which everyone is generally agreed. But the facts of where it died, what caused its death, and where it is buried have remained elusive, the stuff of urban legend—in short, the mystery.

One story had it that when the circus arrived in Flatonia, the elephant’s trainers asked that it be allowed to graze along the railroad right of way. They were advised by local citizens that this wouldn’t be a good idea because weeds there had been sprayed with a powerful herbicide. The story goes on that the circus folk insisted that the elephant was a tough old thing and wouldn’t be affected, though they were soon proven wrong when the elephant promptly died and had to be buried here—presumably somewhere near one of the rail lines.

That the 1911 Argus report indicates that it died before reaching town seems to call the death-by-eating-grass account into question. New research has recently yielded more information, making the story even more interesting, but at the same time raising even more questions. A large front page headline from the February 5, 1914, edition of the Argus proclaims: “WANTS ELEPHANT FRAME . . . A & M College Sending Man Here to Ship Bones to College for Mounting . . . GOVERNOR INTERESTED”.

The 1914 article continues: “On November 23rd, 1911, a large elephant belonging to the Campbell Bros. Shows breathed its last in a SAP Railway car in the yards here, and was buried on the SAP right of way near the Oil Mill”. According to this account, Mr. L. N. Lyon, agent of the San Antonio and Aransas Pass Railway, seeing the usefulness of the elephant’s skeleton ensured that a “good supply of ashess (sic) were placed about the carcass, in order that the chemical action of freeing the bones might be hastened.” Communications between Governor Colquitt, governor of Texas, and Charles Puryear, president pro tem of A & M ensued. By 1914 the time was adjudged to be right for disinterring the bones, and Mr. Lyon was advised of the imminent arrival of Dr. D. M. Francis, of A & M’s Department of Veterinary Medicine, to get the skeleton and ship it to the College for mounting.

Unfortunately, no further mention of this much ballyhooed project is to be found in subsequent editions of the Argus. Inquiries and searches into records of Dr. Francis at A &M and the papers of Governor Colquitt have all failed to turn up further information. We seemed to be at an impasse: was the skeleton really dug up and removed for mounting at A& M? Or was it perhaps found to be already too far decayed to be able to remove it intact? Or perhaps the expedition never materialized at all, and the elephant remains were simply left to rest in peace in Flatonia soil forevermore?

Just when we thought we had reached the end of a very cold trail, however, still another clue to the mystery came to light. In a search this year through the musty, dusty files from Judge E. A. “Sam” Arnim’s law office, two letters regarding the elephant were discovered. In response to a query from someone in Waco, Mr. Arnim wrote in 1977 that he himself saw the elephant being buried.

Though he adds a disclaimer at the end that he was a very young boy at the time and that he was recalling an event more than 60 years prior, he nonetheless describes fairly precisely where he remembered the elephant was interred. This was at a point where 9th Street crossed an S. A. A. P. spur just north of the Flatonia Oil Mill.

Mr. Arnim writes in the second letter that his own recollection was confirmed by Jerome Starry, a still older resident of Flatonia. Mr. Starry also stated that the elephant died in shipment, that the railroad company dug a hole beside the railroad track and pushed the elephant out of the railroad car down into the hole. Tantalizingly, Mr. Starry also referred to the story of the exhumation of the elephant, stating that “he believes the elephant bones were dug up some years later, but is not sure about removal of the bones”.

Now, it seems, we are at least somewhat closer to resolving the mysteries of where the elephant died and was buried, but the question still remains, are the bones still there? A search of the records of the Campbell Bros. Circus housed by the Jefferson County Historical Society in Nebraska, have thus far not provided the name of our mystery elephant, nor even any record of its death and burial here. It is a well-established fact that elephants have long memories, and it seems that the people of Flatonia do as well—perhaps, in time, these questions—and the elephant’s remains—will all be put to rest.

Flatonia Switcher

By W.O. Wood

I guess everyone who has to work for a living is always thinking of finding that banker’s job. You know the one, go to work at nine in the morning, get off at three every afternoon, work Monday through Friday, off on holidays, no dirty greasy clothes, clean hands. Oh, what a dream! Working on the railroad, that is called a retirement job, if you can just get there, as your seniority allows.

I guess everyone who has to work for a living is always thinking of finding that banker’s job. You know the one, go to work at nine in the morning, get off at three every afternoon, work Monday through Friday, off on holidays, no dirty greasy clothes, clean hands. Oh, what a dream! Working on the railroad, that is called a retirement job, if you can just get there, as your seniority allows.

I worked thirty years, all hours of the day and night, always on call, answerable to the phone at all times. In snow, sleet, rain, blizzards, unbearable heat, mosquitos that could hit you like a BB gun. I would get called for a storm train when a hurricane was headed for Galveston Island, leave Houston with six engines and a caboose, come back off the Island with some three hundred cars to get them to higher ground, so salt water would not get in their running gear.

After thirty years, I finally could hold down my retirement job, the Flatonia Switcher. Working with an old head conductor made the job even more sweet; I did not have to watch some green rookie’s every move. Went to work at 7 am, usually off by 3 pm. Sometimes worked till 7 pm, no problem. Monday through Friday, off holidays. Had two pretty reliable engines to work with (no A/C), but I had my trusty little fan that I could plug into the engine’s electrical system. Had water buckets for our ice-cold water bottles. The dispatchers called us the “Road Show”, because we were always on standby to save the day. About forty trains would run through Flatonia daily, between Houston and San Antonio, Hearne and Victoria. Our job was to get the cars designated for our local territory to the customer and spotted for unloading.

Flatonia’s inbound cars came in Monday and Wednesday nights from Hearne to be sorted out and delivered to the appropriate customer. Flatonia proper had Calmaine that received feed products for their many chicken houses in the vicinity. A clay processing plant received raw clay to be processed into specific drilling products. Waelder also has a large Calmaine plant for their chicken feed users. Harwood was our westward terminus, from which we interchanged with the TXGN Railroad (Gonzales) with feed products for Purina, scrap metals for the furnace, and tank cars to be cleaned and stored. Going south from Flatonia, we went to Shiner to deliver different grains to the brewery for the production of beer. We then went to Yoakum to deliver plastic pellets for the production of plastic pipe. Going east out of Flatonia, we delivered tomatoes to AMPI for the production of salsa. American Muffler got steel rolls for their muffler production. Comtech got rolls of steel to make culverts. BWI got a lot of seed, especially during rye season. On to Weimer where MG also got loads of rye seed. Glidden was our eastern terminus, where we spotted crushed limestone and lumber to be treated for landscape timbers. Army trucks were loaded at Glidden, which were manufactured at Sealy’s Stewart-Stevenson, eventually heading to the Mid-East.

Each day was a different day, depending on train traffic and what needed to be spotted and pulled. Some days we may have never left the yard because of congestion. Another day we may have had to help a train that was having trouble. Sometimes we were not able to return to Flatonia and had to ride the carryall (limo) in and start out the next day in the van going back to our engines. Never got boring. And when a hot car would show up for immediate handling, oh boy, the “Road Show” was called into action. The Railroad was ours and get out of our way! We shoved a train all the way to Seguin when they lost their power. Went to Eagle Lake to get hot cars. Went to Caldwell to help a train that had mechanical problems. Went to Cuero when they were going to start loading crude oil.

A lot of history was around these locations out of Flatonia, and I was always open to listening to the old stories of how Oso was moved to a location where the GH&SA Railroad was being built for the establishment of Flatonia. How the town of Praha came about from the original Mulberry. And then the San Antonio Aransas Pass (SAAP) Railroad also being built through Flatonia south to north, crossing the GHSA at the old tower.

When mealtime came around, we looked forward to the Praha and Cistern picnics. The Catholic church at Flatonia put on a good spread. And every Monday was good for the best burger at the auction barn. Other times it may be “veenie weenies” and crackers, or sardines, whatever we had in our grip. Had to make do.

We became friends with the workers at each of our customer sites; they were always glad to see us. We delivered the product that kept their jobs going. Railroad officials were always good to us, never harassing, always showing up with a smiling face, even taking us out to lunch. I have been retired now for ten years; other men came into the Retirement Job along the way. The co-workers and friends made along the rails are missed, but I sure do enjoy retirement. God Bless!

Photo caption: W.O. Wood standing on back of caboose; photo courtesy of W.O. Wood

See Also

Clay: Fayette County’s White Gold

“The road widened to allow for a blacksmith shop with hitching rack along the front, a general mercantile store, with porch and boardwalk leading to the next, a butcher shop, a saloon and a barber shop. Across the road a second general store with a drug store railed off in the rear just about made up the business district of the town of Flatonia, Texas, in the eighteen fifties and early sixties. Each place of business had its hitching rack. Town pump and water trough sat back from the road in a vacant lot. Probably two dozen residences were scattered on both sides of the road. The store with drugs also housed the post office. This briefly was Flatonia, Texas.” (From G. P. Reagan, Country Doctor by Rocky Reagan)

“The road widened to allow for a blacksmith shop with hitching rack along the front, a general mercantile store, with porch and boardwalk leading to the next, a butcher shop, a saloon and a barber shop. Across the road a second general store with a drug store railed off in the rear just about made up the business district of the town of Flatonia, Texas, in the eighteen fifties and early sixties. Each place of business had its hitching rack. Town pump and water trough sat back from the road in a vacant lot. Probably two dozen residences were scattered on both sides of the road. The store with drugs also housed the post office. This briefly was Flatonia, Texas.” (From G. P. Reagan, Country Doctor by Rocky Reagan)

The gang of train robbers met at night in the Flatonia graveyard on June 15, 1887. Around the campfire they plotted the details of their next move: robbing a train about a mile and a half east of Flatonia near Mulberry Creek. The robbery would make international headlines, would secure the notorious gang’s place in Texas history, and would make the town of Flatonia known as the site of “the most daring robbery ever in Texas,” as the New York Sun described it.

The gang of train robbers met at night in the Flatonia graveyard on June 15, 1887. Around the campfire they plotted the details of their next move: robbing a train about a mile and a half east of Flatonia near Mulberry Creek. The robbery would make international headlines, would secure the notorious gang’s place in Texas history, and would make the town of Flatonia known as the site of “the most daring robbery ever in Texas,” as the New York Sun described it. The lawmen rode toward the scene of the crime, but the gang had disappeared immediately after the robbery. The constables did find remnants of the campfire that marked the spot where the train was stopped, as well as horse tracks that indicated that the gang had scattered in different directions.

The lawmen rode toward the scene of the crime, but the gang had disappeared immediately after the robbery. The constables did find remnants of the campfire that marked the spot where the train was stopped, as well as horse tracks that indicated that the gang had scattered in different directions.  I guess everyone who has to work for a living is always thinking of finding that banker’s job. You know the one, go to work at nine in the morning, get off at three every afternoon, work Monday through Friday, off on holidays, no dirty greasy clothes, clean hands. Oh, what a dream! Working on the railroad, that is called a retirement job, if you can just get there, as your seniority allows.

I guess everyone who has to work for a living is always thinking of finding that banker’s job. You know the one, go to work at nine in the morning, get off at three every afternoon, work Monday through Friday, off on holidays, no dirty greasy clothes, clean hands. Oh, what a dream! Working on the railroad, that is called a retirement job, if you can just get there, as your seniority allows.