Fayette County, Texas

and The Civil War

| Fayette County's Civil War Casualties |

Terry's Texas Rangers with Fayette County Ties

Members of the 8th Cavalry, C.S.A., with a link to biographies at the Terry's Texas Rangers web site |

1890 Census - Union Soldiers Schedule

Fayette County entries with rank and regiment |

Confederate Pension Applications

Index of Confederate pension applications made by Fayette County residents. |

Confederate Indigent Families

Index of Confederate Indigent Families in Fayette County (1863-1865) |

The Civil War Letters of Duncan Carmichael

Footprints of Fayette Article |

Civil War Letter [from Anton Hoelscher, Jr.]

Footprints of Fayette Article |

Blue and Grey - Joseph & John Lidiak

Footprints of Fayette Article |

The Confederate Hero of Waldeck

Footprints of Fayette Article |

Draft Resistance in Fayette County

Footprints of Fayette Article |

German Draft Resistance in 1860s Central Texas

Footprints of Fayette Article |

The Volunteer Aid Society

Footprints of Fayette Article |

Yankees at La Grange

Footprints of Fayette Article |

Reminiscences of the Boys in Gray

A collection of memoirs, including those of Oscar W. Alexander, John W. Hill, Jesse Austin Holman, and Natt Holman, published by Mamie Ann Yeary

Part of the Terry's Texas Rangers Online Archives |

Terry's Texas Rangers, The Reminiscences of J.K.P. Blackburn

A memoir originally published in the Southwestern Historical Quarterly.

Part of the Terry's Texas Rangers Online Archives |

Meeting of Ex-Confederates

La Grange Journal account of first meeting of Fayette County ex-Confederates in November 1891 |

Civil War Letters of John W. Rabb

Twenty-three letters written during the Civil War describing Rabb's ordeal

Part of the Terry's Texas Rangers Online Archives

|

| Creuzbaur's Battery and Fayette County, C.S.A. Historical Markers |

Tennesee Baptist Newspaper Article regarding Sick Soldiers

November 16, 1861

Contributed by Vickie O'Bannon-Johnson |

Maryville, Tennessee Newspaper article regarding the death of Samuel Grover

August 11, 1932

Contributed by Elaine Russell

|

Draft Petition for Alexander Schecke, April 2, 1862

Texas State Library and Archives Commission

Image, signed petitioners include A. L. D. Moore, Wm. M. Short, FW Dodson, Bartlett Zachary, Jas. W. Miller, Charles Fredrick, Jordan Gay, A. M. Short, H. S. Hinald, J. A. Trousdale, Henry Moore, J. E. Moore, Wm. J. Rufall, Wm. Friedlander & Bro, John V. D. Bleeken |

Isaac Sellers' Letter to His Nephew

Describes his and his brothers' service to the Confederacy |

Fayette County's Civil War Casualties

This list is a work in progress. Please contact site coordinator if you can provide additional information.

Seibelt Hinrich Behrens

28 Mar 1829 - 9 Jun 1863, private in the Long Prairie German Company and Company E of Waul's Texas Legion; died of wounds at Vicksburg, Mississippi

G. F. Byerly

Company C, 8th Texas Cavalry Regiment, possibly from Fayette County, died of illness November 1861 at Nashville, TN

N. P. Cheatham

Company F, 8th Texas Cavalry Regiment, died of illness, buried in Confederate Circle, Mt. Olivet Cemetery in Nashville, TN on January 9, 1862

David Fulton Douglass

Company K, Allen's Regiment, Texas Infantry, died at La Grange on December 30, 1863 from diseases contracted while a soldier

Edward Herbert Eanes

Company F, 8th Texas Cavalry Regiment, died of illness on November 4, 1861 at Bowling Green, KY

Henry I. Etzel

Samuel H. Grover

Company F, 8th Texas Cavalry, Terry's Regiment, killed on November 15, 1863 at Rockford, TN

William Guehrs

Creuzbaur's Battery, 5th Texas Light Artillery, wounded at Calcasieu Pass, Louisiana, died 3 Sep 1864 at Waldeck from wounds

See Footprints of Fayette article, The Confederate Hero of Waldeck

J. L. Harris

Company F, 8th Texas Cavalry Regiment, died at Decatur, AL in 1863

Silas Calvin Izard

Capt. Company D, Waul's Texas Legion,

died December 14, 1862 in Granada County, Mississippi

[4]

Sterling B. Izard

Company D, Waul's Texas Legion, enlisted December 13, 1861 at Galveston, died November 12, 1863, buried at Durant, Holmes County, Mississippi.

[4]

William Kneip

Creuzbaur's Battery, 5th Texas Light Artillery, killed May 6, 1864 at Calcasieu Pass, Louisiana

Carl Kreidel

Company E, Waul's Texas Legion

J. M. McCalester

Lt., died March 18, 1864 of a wound received in a battle between Forest and the Union in Mississippi

Cincinnattus J. McCollum

Sibleys Brigade, died February 18, 1862 at Alamosa, New Mexico [1]

T. G. Mercer

Company F, 8th Texas Cavalry Regiment, died from illness at Bowling Green, KY on November 9, 1861

John Novak

Mounted State Right Guard, son of Matthias Novak

Absolom O'Berry

Company K, Texas 2nd Infantry, one of five brothers killed during the Civil War

Eli O'Berry

Company K, Texas 2nd Infantry

Israel O'Berry

Company K, Texas 2nd Infantry

James O'Berry

Company K, Texas 2nd Infantry

Joseph O'Berry

Company K, Texas 2nd Infantry

J. P. Phillips

Company F, 8th Texas Cavalry Regiment, buried in the Old Nashville Cemetery on December 26, 1861, in 1869 reinterred at Confederate Circle, Mt. Olivet Cemetery, Nashville, TN

Anton Richers

Private in Dege's Battery, shot for attempted desertion [news article below]

Fritz Schaefer

Company G, Fourth Regiment, Texas Cavalry. He was killed in the Battle of Glorietta Pass, New Mexico. His brother, Charles, later joined the same group and survived the war.

Hinrich Enno Schumann

30 Oct 1841 - 10 Nov 1862, private in the Long Prairie German Company and Company E of Waul's Texas Legion; died of illness at Oxford, Mississippi

Samuel A. Street

Company F, 8th Texas Cavalry Regiment, killed near Marietta, GA in July or August 1864

Dr. John Sutton

Wilk's Regiment

[3]

Alex von Rosenberg

Creuzbaur's Battery, 5th Texas Light Artillery, died in a military hospital at Liberty on October 2, 1864; buried at Liberty [2]

J. W. Yarbrough

Company F, 8th Texas Cavalry Regiment, died of illness and buried near Nashville, TN on November 24, 1861

1. Information regarding Cincinnatus McCollum from Tammie Smith

2. Information regarding Alex von Rosenberg is from Neale Rabensburg

3. Obituary

4. Information regarding the Izards is from Holley R. Izard

|

Tennessee Baptist, November 16, 1861, p. 2, c. 2

Sick Soldiers.

There are in this city not less than one thousand soldiers who have been sent down from the camps in and about Bowling Green, Ky. The larger portion of these are from Texas, and lower Mississippi. The Texas Regiments are suffering most severely. Fully one half of them are on the sick list. The unoccupied warehouses in this city have been, and are still being fitted up for hospitals. For the want of room these places are so crowded with cots that it is with difficulty one can pass between them, and the result is and will be to an alarming extent, that they will become vast pest houses in spite of all the attention by a far too inferior medical staff, and the attention of a class of our ladies, which in justice to them we must say we never saw equalled. Nashville has done and is doing much, but she is able to do more and infinitely better than she is doing. There are fully two thousand families in this city and within five or six miles able to take in and nurse from two to a half a dozen of these suffering boys, and we think that it should be done—that it will be a dishonor to us unless we do this, for these are not mercenary soldiers but the noble sons of the noblest blood of the South, who have volunteered to interpose their breasts as shields between this city and community and the invading and merciless foe. What do we not owe to them and should we not feel willing to do for them? We have written articles for our city papers upon this subject, which may have attracted the notice of our readers in this county, by which they will have been apprised of the movement we have successfully inaugurated and may be promptly to cooperate. There are many soldiers who can ride ten or fifteen miles into the country, who must have rest, quietude, and nursing for a week or two or succumb to the disease that is fastening upon them. Those who live too far to take a soldier, can aid those who are nursing them, or the General Hospitals, if any are left to suffer there; we say if any are left, for we are happy to state that since the publication of the first article, hundreds have been taken into warm Southern homes, and scores are being taken daily. Brethren from the country—come in with your buggy or carriage at once and take one or two. Let us do something worthy of our much talked of hospitality—and come promptly to the relief of the poor suffering soldier.

To Parents and Relations in Texas, Arkansas and Mississippi. TO THE FRIENDS OF SEVERAL SOLDIERS IN THE S. W. We have the pleasure of nursing under our roof, the following soldiers: Chatham, Huntsville, Texas, convalescing rapidly, Leonidas Tucker, Bradley co., Arkansas, much improved; T. W. Campbell, Arizona, improved; Calvin Milner, Leake co., Mississippi, case hopeful; W. N. Hodge, Fayette co., Texas, very sick, doubtful; Leonard, Waco, Texas, convalescing; Elder J. J. Riddle, has so far recovered as to join his company.

Contributed by Vickie O'Bannon-Johnson

Maryville Enterprise, Tennessee, August 11, 1932

SAMUAL [sic.] GROVER C. S. A. SOLDIER

During the Civil War of 1861-5, two Texas Rangers of the Confederate army, retreating out of Knoxville, came to Rockford, near 10 miles South, and at the Rockford Cotton Mills asked to see if any had arms or why they were not in the army.

Richard I. Wilson, in charge, told them that all men were assigned to work there, by the Confederate Military Authorities and some were armed to protect themselves and the Mill. In a controversity[sic.] a nephew of Wilson, Charles Coffin, made one of the soldiers angry, and he shot Coffin above and between the eyes, bullet coming out near the base of neck. Some one in the crowd about them, killed one of the soldiers and wounded the other. The wounded soldier escaped on his horse, crossing Little River at the ford below the Mill and going on toward Louisville, he came to the home of Dr. Madison Cox. There his wound was dressed and he cared for [sic.] until he was able to go on. He and the said Charles Coffin had recovered, and joined the Company he belonged to. The dead soldier was taken by the Mill hands across the River and near the line fence, afterwards belonging to W. L. Russell and Capt. James Walker, but all at that time belonging to Samuel Wallace, there buried and near the grave on a Hickory Saplin[sic.] was carved the name "Samuel Grover". The dead and wounded were taken into the back room of the office and commissory of the Cotton Mill and amongst those going to look at them was a small lad and his grandmother. This lad is now aged and sick at home, on Main street, in Maryville, Tenn. His name is William Wine. His father was then in the Mill; he tells the story hoping that some relative may be pleased to learn where and what became of the named soldier. The grave was on a small knoll on the land that then belonged to the Cotton Mill property, on south and west side of Little River. The grave has long ago disappeared as after many years had elapsed the land was cleared and farmed over. The Walker lands included this spot and the children of this family remember the Grave and marked tree. This was related to the writer on August 2, 1932, and it may be copied into Texas papers for information to the family, if any are alive. The Cox family call to mind the father speaking of the same.

"Tab".

Contributed by Elaine Russell, United Daughters of the Confederacy, Maryville, TN, who would like permission from a family member to order a military marker and place it in the vicinity of his burial place.

Dallas Daily Herald, March 23, 1865

A military execution took place at Galveston, on the 3rd inst. Antonio Ricker [Anton Richers], of Fayette county, and a private in Dege's Battery, was shot for attempted desertion to the enemy. While the execution was going on a portion of his company arrived on the ground with two field pieces and attempted to prevent the execution. The attempt was easily put down. Documents had been sent to Gen. Walker the previous day, showing that Ricker was not of sound mind, and the Gen. had respited him, but the telegraph wires being down, the dispatch did not reach Galveston until 12 minutes after the execution had taken place.

Footprints of Fayette

The following Footprints of Fayette Articles about the Civil War were written by members of the Fayette County Historical Commission. They first appeared in the weekly column, "Footprints of Fayette," which is published in the Fayette County Record, Banner Press, Flatonia Argus, Schulenburg Sticker, and Weimar Mercury newspapers.

The Civil War Letters of Duncan Carmichael

Contributed by Carolyn Heinsohn

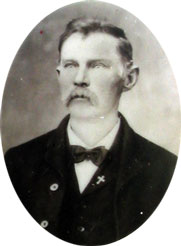

Duncan and Martha Ann Burleson Carmichael, circa 1859

|

The following letter is one of forty-one written by Duncan Carmichael to his wife and relatives during the Civil War. Most of the letters are in the possession of his great-grandson, Donald Boehnke of Muldoon, and were compiled into a book that was published by his great-granddaughter, Zia Crowell Miller of Matagorda, TX. A copy of her book has been donated by Mr. Boehnke to the Fayette Heritage Library and Museum. The details of Carmichael’s poignant letters are very descriptive, giving insight into the daily lives of the soldiers in his company, their whereabouts and his feelings regarding the war.

Duncan Carmichael, born in South Carolina, moved to Texas in 1856 with his parents and siblings, eventually settling between Cistern and Waelder. He married Martha Ann Burleson of Missouri in Bastrop County in 1859. They settled at Oso, east of Flatonia, and then in Pin Oak, which was south of Muldoon. Enlisting in the Confederate army in 1861, Carmichael served in the 26th Texas Cavalry, Xavier B. Debray’s Regiment, Trans-Mississippi Department, District of Texas, Sub-Military District of Houston. He left Martha Ann, who was barely 20 years old, with two babies to rear while he was at war.

Carmichael suffered greatly from fevers in the summer of 1863 and was hospitalized in Houston for several months. Illness plagued him during the war years and for the remainder of his life. Duncan died in 1886, leaving his wife and nine children, and was buried in the Pitman Cemetery in Muldoon.

Galveston, Texas, July 18th, 1863

Dear Wife,

Received your letter of July the 7th, yesterday evening and now send you a few lines in answer. My general health is considerably better and my cough is better but I have pain in my stomach and soreness and dysphoria very bad. It keeps my mind wrecked and makes me feel despondent all the time. My appetite is not too good and when I eat it hurts me. My strength and flesh is sufficient to do duty and I expect to go on as soon as our Co. gets here. Our Co. is at Houston and will be here in a few days. They were paid off yesterday, and I and Mc got cut out of our pay by not being up there but perhaps we can get to go up and get it. Mc’s health is bad [James McClure Burleson, brother of Martha Ann Burleson Carmichael]. He has not recovered since he was sick but is able for duty. Fox Terry is here and well. He told me of Huff’s death. There is considerable sickness here but it is not very fatal. It is mostly dysentery and slight fevers & etc. This is a beautiful place and it would be a pity for it to fall into the Yanks hands. I would like to live here. Vicksburg has fallen into the Yanks hands as I guessed and 25,000 men. And Port Hudson (Louisiana) has also fallen with 10,000 more and there is now despondency & gloom resting over our country and our cause looks gloomy and our prospects almost hopeless. A great many are ready to give up and submit to the Yanks while others swear vengeance and death before submission. As for me, I think we will have a long and dreadful war and will succeed in the end. We will soon have a regular gorilla (sic) war, all over the country, like the old Revolution War. The President has called out about 100,000 militia and General Magruder has called out all the militia up to 50 years and one fourth of all the Negro men in Texas and the men over 50 are ordered to organized (sic) for home defense and etc. & etc. Now from the signs it looks like we are to have trouble soon. It is thought we will be sent to Louisiana soon but I hope not.

The home of Duncan Carmichael after the Civil War - the smaller section on the left is the original home; the section on the right is a later addition; Bethany community, west of Muldoon.

|

Galveston is a perfect military camp now. The soldiers are quartered in the houses and the most of the citizens are gone and their houses shut up. Great activity prevails among the soldiers here. They drill 4 hours every day, 2 in the morning & 2 in the evening, one day on horseback & one on foot. There are 4 regiments here, 1 cavalry & 1 infantry regts (sic). The drum & bugle & fife are sounding all the time. I wish you could see 3,000 men drilling; it is a beautiful sight to hear the brass band & the drum & fife & see the men in their uniforms & their glittering muskets & sabers & bayonets & etc. It puts an awful & solemn feeling on me to see them. There are Negroes here working on breastworks all the time & the Island has redoubts & batteries all over it nearly, but I do not think it can be successfully defended against the Yanks. Now, I am sorry that all the men have to leave the Creek but I hope Mr. Anderson will stay & help the poor women to gather their corn. You must let Van help them & my wagon & steers & etc. can help them. Now do the best you can. I do not know whether you will ever see me again or not but I hope you will. The blessed Lord has brought me safe this far & I hope he will continue His protection to me. Now is a time that will try men severely & it seems the tide of war is against us at the present. If I am to die by the hands of Yanks, it will leave you in a bad condition but if it is the Lord’s will, you must try to bear it. If I ever get in a battle, I expect to sell my life as dearly as possible - Give my respect to Mrs. Anderson & Mrs. Hopper & all inquiring friends. Write often & tell Lizzie to write to me & let me know where Mr. Mc is & etc. Give my respects to your father & mother & all the family.

Yours Affectionately, D. Carmichael

Source: Miller, Zia Crowell. The Civil War Letters of Duncan Carmichael. Bay City, Texas: Lyle Printing.

Civil War Letter

by Carolyn Heinsohn

This letter dated June 29 (no year) was probably written to Joseph Hoelscher by his older brother Anton Hoelscher, Jr. in 1863 during the Civil War. Joseph enlisted in the Texas State Troops – Dixie Rangers, Active Cavalry Company, Fayette County, TX. in June, 1861. Their headquarters were at Fayetteville, TX. He became a First Lieutenant in the 22nd Brigade, Texas State Troops, in May, 1862. Joseph and his family lived at Ross Prairie, northeast of Ellinger, TX.

On January 13, 1863, Anton Holscher, Jr. (Hoelscher) enlisted in Captain Z.M.P. Rabb’s Company of Unattached Troops, 22nd Brigade, CSA, stationed at Columbus, TX. He served as a teamster for Messrs. Folsom and Sanborn under Major General Magruder. Anton and his family lived between Live Oak Hill and present-day Ellinger, TX.

The original letter was written in German.

June 29

Dear Brother,

We came back from Braunsvil1 three days ago. Thank God we are all well.

Bernard’s (their brother) wife and children are doing fine. We also have been to your house and they are doing well, too. In Braunsvil we bought a lot of clothes and we gave everybody some. Also to Rob and Beling and for all of us.

Now about our trip to the chaparels2 We were 6 wagons, Joseph with 3, myself, Birkman and your wagon. For half we received 1 bit3 per pound freight. In Braunsvil, we got to deliver flour to Columbus. Every tenth sack went for the soldiers. Everything under 50 (2 C4 gold and paper) had to go to the government store. Now I think I can count on 3-4 weeks; then I must go once again because everybody under 40 who does not drive for the government do not get a detail anymore and I think your wagon should be licensed for such a trip. Then I will go for half again and your wife will also get something. I would rather stay at home than travel so far, but I would rather drive than be in camp.

Now some news. Alsander resigned; Fricke is a captain.5 While we were driving through Braunsvil the artillery and the infantry regiment where Fricke belonged were marching on their way to Colorado.6 And they did not know anything else. On June 24 we were in Switham.7 The women want to let the cotton stand until the men are able to come home.

Bernard’s wife sold 3 young oxen for $56. Oxen are very expensive. Wilhelm’s [their brother] field is all planted like last year. Millet is bad; wheat and cotton are good and everything is ersted.8

Things are scarce here, but your family has not been hungry. Bacon, bread and beef are plentiful, so be of good cheer. If you just come back healthy everything will be fine.

Paper money is doing bad, 5 to 1. But it does not make any difference. We have enough to live on and we can still get clothing. If only there would be peace!

Now something else. All our relatives are still healthy. I hope the same about all of you. Wilhelm’s wife said yesterday: “If they will only come back by Christmas, then I will be happy.”

This is all I know. Patience, my boys, do not lose your courage. God will direct you happily together. This is what I wish for you. It is all I can do. God’s blessing. Mary full of grace, help us.

Best regards from Herrman [Beimer – married to Anton’s niece Lucy Buxkemper], Elisabeth [his sister, married to Theodore Buxkemper] and mother [Mary Catherine Hoelscher]. They were here Sunday and said everyone is still healthy and in the old trot.9 Mother stayed at your house this week. Bernard’s people were still healthy 5 days ago.10

Your loving brother,

Anton Holscher [Hoelscher]

On page 2 of the letter, four lines are written upside down in the upper margin: “On the 6th of July there will be drafting of those from 18 to 50 years, without exemption of shoemaker and tailor. That is again serious for us. I do not know yet how bad it will result for us and what they are headed for.”

Carolyn Heinsohn is the great-great granddaughter of Anton Hoelscher, Jr.

Notes

1. German spelling for Brownsville on Texas-Mexico border

2. The “chaparral” is the flat, thorny mesquite-covered land of South Texas.

3. 1 bit = 12 1/2 cents

4. 2C is probably $200; C being the Roman numeral for 100.

5. This is a clue that the addressee might be Joseph, Anton’s brother, since both of them were in the 22nd Brigade. Anton writes as though the addressee would know Alsander and Fricke.

6. Possibly referring to Colorado County

7. Location of Switham is questionable; it was a two-days’ ride from Anton’s home near Ellinger, as they had been back three days when this letter was written, and they were in Switham on the 24th

8. “ersted” refers to the first plowing

9. “in the old trot” is like “in the same old rut”

10. Bernard’s family lived in the Content area of Colorado County, which was three miles away from present-day Weimar. If Anton saw them five days before the letter was written, it was also on the 24th. Therefore, Switham must have been in that area of Colorado County.

Blue and Grey - Joseph & John Lidiak

by Judge Ed Janecka

The tragic Civil War that our nation endured had many stories. It was a war unlike any other, in which fathers fought their own sons and brothers fought their own brothers. Occurrences such as this were not uncommon. One such story happened here in Fayette County.

Joseph Lidiak was a native of Moravia, born on February 12, 1824. In the mid-1800's, he set out for American with his family, including his first John who was born on June 2, 1846. They arrived at the port of Galveston in November of 1860, becoming the first Lidiak's to come to America. Upon arrival, they took a wagon to the Bluff area. The area that is called

Hostyn today was first called Bluff and then later Moravan. The town was officially given the name Hostyn in 1925. There, Joseph and his family settled in, and he farmed until 1863. He then enlisted in the Confederate Army and became a corporal in Martindale's Company. For most of his training and service he was kept in Texas. As a favor, John, his eldest son, hauled cotton to Brownsville for a neighbor. On his way back, John met some friends who were enlisting in the Union Army, and after a while, they finally persuaded him to join. Unaware of his father's enlistment in the Confederate Army, John joined Hammet's Company, the First Texas Cavalry of the United States Army. Having been a resident in the United States for only two years, John found himself fighting on the opposite side of his father Joseph. Although no records exist that show that the two men fought against one another in the same battle, it is possible that they crossed paths during the war. Both survived the grueling war and returned home to Hostyn, where they lived together on the family farm. In 1869, John Lidiak helped build Hostyn's first church. Today, the father and son are buried side by side in the

Hostyn cemetery, and both Joseph and John have a cannon dedicated in their honor on the church grounds.

The Confederate Hero of Waldeck

by Harvey Meiners

William Guehrs was born January 1841 in Brandenburg Prussia. Guehrs was a young German immigrant who arrived in Texas shortly before the Civil War and made his home at Waldeck (then known as Long Prairie) in Fayette County.

William Guehrs was born January 1841 in Brandenburg Prussia. Guehrs was a young German immigrant who arrived in Texas shortly before the Civil War and made his home at Waldeck (then known as Long Prairie) in Fayette County.

On October 12, 1861 Guehrs, along with his friend, Conrad Frosch, enlisted in Creuzbauer's Battery of the Confederate Army. The battery was made up of German Texans from Fayette County.

Edmund Creuzbauer, a former Prussian artillery officer, organized Creuzbauer's Battery. It was composed of around 150 men, 4 cannons, 72 horses, and 39 mules.

After serving a short tour of duty on the Rio Grande near Brownsville they were transferred to Fort Griffin, Sabine Pass.

On May 4th, 1864, the battery, along with an attachment of infantry and cavalry, received orders to move to Calcasieu Pass, Louisiana, and two miles inland from the Gulf and south of Lake Charles. After 25 miles of difficult travel through marsh and sand grassland they made contact with the enemy on the 6th of May 1864. The enemy consisted of two Union gunboats, the Granite City and the Wave. The mission of the gunboats was to impress food and supplies from the residents.

By dawn of May 6th, the guns were in position some 1200 yards from the Granite City; farther up to the left was the Wave.

At Gun #1, Sergeant Alex von Rosenburg prepared his small crew for action, at his side stood his brother, Walter, as gunner. Cannoneers were John Winn, William Guehrs, Will Peters and the Kneip brothers, Henry and William, from Round Top.

With the horses and mules safely in the rear, the crew positioned the gun, sighting the barrel towards the Granite City. Private Guehrs "wormed" the barrel of grit and sand, then loaded the first round. The crew of four waited for their signal to fire in the gray light of the May morning.

The order came and the guns roared their surprise. Six or eight times they fired across the water before the enemy returned with deadly fire in the midst of Gun # 1. William Kneip was killed outright and William Guehrs was severely wounded in the leg. The crew frantically moved the gun into another position and continued to fire. Henry Kneip continued in spite of the loss of his brother, because he felt desperately needed. William Guehrs, fighting pain and blood loss, refused to be taken to a field hospital and continued to "worm" load and fire his cannon in a kneeling position in the sand and muck of the swamp.

The battle lasted 75 minutes until both the Granite City and the Wave surrendered. One ship was hit 65 times. Both captured ships were returned to service for the Confederate cause.

The battle won, Guehrs let his friends assist him to the field hospital. His wounds were treated, but the surgeons quickly realized that he needed extensive care for rehabilitation.

With a medical furlough in his pocket and accompanied by his friend, Frosch, Guehrs left Creuzbauer's Battery to recuperate at Frosch's home in Waldeck.

He lingered all summer suffering from complications and infections. The injuries finally proved too much and on September 3, 1864 he passed away.

Today, Private Guehrs lies buried in the Waldeck Cemetery yet, those who seek his last bivouac search in vain for the stone that marks his grave. There are many buried in the northern part of the cemetery and wooden crosses only marked many graves during earlier years. Grass fires and time has contributed to the loss of these locations, but somewhere in this open area lies this Confederate hero, only one of four Confederate Medal of Honor recipients in all of Texas.

The memory of Private William Guehrs is not forgotten as the C.S.A. Medal of Honor was posthumously awarded and dedicated in 1996 at the Imperial Calcasieu Museum of Lake Charles.

It is the hope, desire, and goal of the community of Waldeck to be able, with the help of interested Veterans organizations and others, to erect a fitting monument in his honor, commemoration the valor of this immigrant cannoneer who ignored a mortal wound to fight for his adopted country in the hour of peril.

Draft Resistance in Fayette County

by Gary E. McKee

1861, the secession of the Southern states of America begins. Texas was the seventh state to leave the Union and the last to leave before the firing on Fort Sumter.

Fayette County was the home to a large amount of newly arrived European immigrants, who had left their homeland for a number of reasons including continuous civil wars and forced military service for the young men. These new Americans were actively trying to scratch out a living for their families on their small farms. When the statewide vote for secession was held February 23, 1861, the voters rejected leaving the Union by a margin of twenty, out of 1180 votes cast. In 1859, there was 250 German voters in the County. While they probably voted pro-Union, this number indicated an equal number of "American" voters.

In April of 1862, the Confederate Conscript Law was enacted requiring all men between the ages of eighteen and thirty-five to serve in a branch of the military for three years. The men of Fayette County reacted in several ways: some joined up and served heroically on battlefields such as Glorietta Pass, Vicksburg and Shiloh; a large number joined local Texas State Troops, which were formed to protect Texas from invasion, and several men disappeared into the deep woods to wait out the war.

In 1862, local Confederate General William G. Webb received information that local citizens, of mostly German ancestry, were holding meetings to oppose the draft. In January of 1863, a delegation of Germans visited General Webb and presented a written declaration. This brave letter of defiance is an excellent test of democracy in time of war, but also gives a great snapshot of life during this time:

Brig. Gen. William G. Webb, La Grange

At a public meeting held by the citizens in Biegel Settlement, Fayette County, Texas, on January 4, 1863 the following declaration was adopted as an expression of the sentiments of said meeting:

The measures taken by the Government to protect this State against invasion are so far-reaching and serious in their consequences that they fill our minds with dread and apprehension.

The past has already taught us how regardlessly the Government and the county authorities have treated the families of those who have taken the field. We have been told that they would be cared for, and what put of this time has been done? They were furnished with small sums of paper money, which is almost worthless, and which has been refused by men for whose sake this war and its calamities were originated.

Last year we made tolerably good crops; the prospect for the next is not very encouraging, and we cannot look forward with indifference upon starvation, which we apprehend for our wives and children.

Although it has been said that we will not be needed for more than three months, the time for planting will then be over and our children may go begging for the small pay which we are to receive for our services is insufficient to purchase bread for our families and pay for it. We and our families are almost destitute of clothing, and have no means of getting enough to protect us even imperfectly against the cold, from which cause sickness and epidemics result, as has been experienced in the Army, where more men have fallen victims of disease than by the sword of the enemy.

Last autumn we applied to procure cloth from the penitentiary, but up to this time we have not been able to obtain any, whereas Negro holders, whom we could name, can get such things and fetch them home. For these reasons we sympathize with all the unfortunate who have to provide for their own maintenance, and hope that our authorities will look upon us as men and not as chattels. With what spirit and what courage can we so situated fight, and that, moreover, for principles so far removed from us?

Besides the duty of defending one's country there is a higher and more sacred one—the duty of maintaining the families. What benefit is there in preserving the country while the families and inhabitants of the same, nay, even the Army, are bound to perish in misery and starvation?

In view of the foregoing we take the liberty hereby jointly to declare that unless we obtain a guarantee that our families will be protected, not only against misery and starvation, but also against vexations from itinerant bands, we shall not be able to answer the call, and the consequences must be attributed to those who caused them.

Furthermore, we decline taking the army oath (as prescribed) to the Confederate States, as we know of no law, which compels Texas troops, — to take the same.

It is the unanimous wish of those assembled in this meeting to apply to Brig. Gen. W. G. Webb to use all of his influence to the effect that the men now drafted for militia service be permitted to stay at home until they have finished planting.

By authorization and in the name of about one hundred and twenty citizens.

C. AMBERG, H. BAUCH, R. HILDEBRAND

H.KRALE, H. HASSE.

I do hereby certify the above and foregoing to be a true and correct copy of the original (translation).

JAMES PAUL,

Private Secretary

This letter prompted General J. B. Magruder to declare martial law in Fayette, Austin and Colorado counties. General Webb notified Texas Governor, Francis Lubbock, who immediately visited La Grange for several days and gave the German delegation a very plain, positive talk. Cavalry troops from Arizona were brought in to patrol and enforce the draft. By the time the troops arrived, most of the Germans had gone into the militia, which enabled them to stay in the area and tend to their crops and families.

German Draft Resistance in 1860s Central Texas

by Gary E. McKee

The role of Germans in the Civil War has been portrayed mostly as anti-war agitators. The dissidents and their activities made good headlines and instilled a blanket condemnation of Germans by the Anglos. After much research, this historian has concluded that most Germans had responded as any human might do under these circumstances. It was based on the individual, not his ethnicity.

In 1860, in Texas, out of a population of 600 thousand, there were 20,000 citizens who were born in the German states. At this time Texas was settled only 100 miles west of Interstate 35 with German founded Fredricksburg being the frontier. The Germans stood out because they spoke their native language and had not yet integrated into the political/business realm of Texas.

It is true that some Germans had left their homeland because of required military service, and when forced to change allegiance and take arms against the nation that had offered them salvation, the majority acted predictably: they resisted. Some men disappeared into the dense river bottoms to wait out the war and were supported by their families. The number of resistors was enough that they formed small encampments with a military structure. Some men who had fought, been wounded and sent home to convalesce, joined these bands rather than return to the army.

It must be noted that this resistance was not uniquely against the Southern cause by the fact that the New York City draft riots of 1863 were led primarily by German citizens (Germans composed 25% of New York City). Federal troops were recalled from the battlefield to suppress the rioting in which over a thousand citizens were killed. In Ohio, Germans attacked Union draft officers and lynched them. This action contrasts greatly with Austin County, Texas where Germans merely beat the Confederate draft officers with branches and iron rods.

Another popular explanation of German draft resistance was the opposition to slavery. In 1850, there were twelve German slaveholders in Austin and Fayette counties, roughly one-tenth of all German property owners. Most owned fewer than five slaves, but one German owned fourteen and another twenty-seven slaves. Friedrich Olmsted, one of the most astute of contemporary German observers noted that “few of them [Texian Germans], concern themselves with the theoretical right or wrong of the institution [slavery], and while it does not interfere with their own liberty or progress, [they] are careless of its existence.” Most Germans arrived in Texas fiercely independent and financially strapped. Once they found land they immediately began farming to support their families and had little time for politics or other activities outside of their self sufficient, secluded farms.

This lack of support for the new government bred suspicion and paranoia from the established Anglo/Texians. The newspapers periodically ran editorials questioning the patriotism of the newly arrived immigrants and their lack of desire to learn English.

When the statewide vote for secession was held in February,1861, the Fayette County voters rejected leaving the Union by a vote of 580 for secession and 626 against secession. Earlier census revealed approximately 250 German voters in the county. While they probably voted pro-Union, this number indicated a more than equal number of “American” voters.

In June of 1861, when the war draft was announced, General William G. Webb of La Grange reached out to the Germans by including in his General Order #1 that: “Our adopted citizens from the Old World also have brave hearts and stout arms and are ready and anxious to meet the common foe...”

Fayette County responded by organizing 19 home guard companies of which one was named the German Company. Two companies of men volunteered for the regular army, of which there is a sprinkling of German names. The quantity of Germans in the regular army is noted by the Confederacy providing training manuals in German. After it became obvious that the war was going to be a long, drawn out affair, the draft numbers and length of service was increased. This forced service increased the resentment of the German population and they began holding organized, democratic styled meetings.

Numerous reports reached General Webb of large bands of armed men, meeting in Fayette, Austin and Colorado Counties to devise methods of resisting the draft. Abolitionist and future reconstruction governor A.J. Hamilton, then practicing law in La Grange, was rumored to be assisting the Germans and organizing a slave revolt.

In November, 1862, the enrolling officer for Austin County sent Webb a list of thirty two men who were all German, except four. In his words: “They are remarkably stubborn, and I am satisfied do not intend to submit to enrollment... Sundry meetings have been held to concert measures of resistance..the meetings were held in secret...the last, a public meeting, in which they resolved to petition to the Governor, asking that their families be provided for and themselves armed and clothed, as a preliminary to their submitting to the laws and entering the service. These meetings were largely attended by 400 to 500 persons.”

On January 2, 1863 , the result of a meeting held in Biegel (between Fayetteville and Rutersville) was a letter, written in German, addressed to General Webb. The letter focused on the impact of the draft on those left behind rather than the character of the men. (“Besides the duty of defending one’s country there is a higher and more sacred one—the duty of maintaining the families”).The letter stated that they were organized and made valid points against being drafted. The group stated that the government has failed to provide adequate support for the families left behind as the draft would occur just prior to planting time (“we cannot look forward with indifference upon starvation, which we apprehend for our wives and children”). The group pointed out that their families were unable to obtain cloth from the penitentiary looms, yet prominent slave owners had full access. The Germans recounted their desire to be free men (“that our authorities will look upon us as men and not as chattels. With what spirit and what courage can we so situated fight, ... for principles so far removed from us?”). After stating that they refused to take the oath of allegiance to the Confederacy the tone of the letter softened by requesting General Webb to delay the draft until planting time was over. The letter was signed by approximately 125 men.

This example of democratic principles triggered martial law in Fayette County and troops with a cannon were brought in to enforce the draft. Governor Lubbock visited La Grange and talked to the leaders of the Germans. This combination quieted down the situation, but General Webb deduced that the real reason of the organized resistance was that Union spies were working in conjunction with the Yankee invasion force that had just captured Galveston. The Yankees would them make a swift run through the heart of Texas while home guard units were distracted by the German resistance efforts. This plot was foiled by the recapture of Galveston by Confederate forces under Colonel Thomas Green from Fayette County. Webb concluded that “this movement is not confined alone to Germans but men of our own race and country”.

The details of this “uprising” was not brought to light until Union prisoners at Hempstead began naming names and five local men were arrested. After a controversial civil trial the men were found not guilty, however the military courts ordered them banished from Texas. They were escorted to Eagle Pass and forced to enter Mexico.

The struggle to stay alive and care for the returning veterans of all ethnicities in this harsh time occupied citizens as the war wound down.

The blanket descriptive term of Germans as used by the authorities to describe the dissidents, overlooks the German contributions to the southern side of the war.

The German trait of mechanical talent was recognized as necessary to the economic survival of the area and war effort. There were numerous requests to be exempt from the draft by the men who maintained the cotton gins, grist mills, tanneries, and factories which produced war materials. These exemptions had to be signed by a number of local witnesses attesting to the importance of these men. The witnesses were both Anglo and German.

The evidence of individuality comes from the considerable number of Germans who immediately joined the army. Their reasons varied from patriotism to “I'm 18 and this sounds exciting”, which is the reason most men have volunteered for military service in America.

From the southern part of Fayette County, Louis Strobel (a German living in Ft. Bend County) raised a company which included many Germans, and was assigned to what would become known as Terry's Rangers. This unit of the 8th Texas Cavalry were used as “shock troops” in leading assaults in Kentucky, Shiloh, Murfeesboro, among others. Ironically, one of their officers was Thomas Lubbock, the brother of the Governor who had come to La Grange to smooth out the tension.

From the High Hill area, a company of Germans enlisted under Ernst Creuzbauer and they served uneventfully as an artillery unit along the Mexican border until ordered to the Louisiana-Texas border when the threat of a northern invasion became known in that area. Creuzbauer's men ambushed and captured two Union ships as they sailed from the Gulf through Calcasieu Pass to resupply from Union sympathizers in Louisiana. William Guehrs, who had very recently come to Texas from Germany, was severely wounded several times and was posthumously awarded the Confederate Medal of Honor, In Waldeck, there is a befitting monument to Guehrs bravery, who, severely wounded, remained at his cannon, firing shots into the Union boats. After the battle he returned to the Waldeck area to convalesce but died from his wounds in 1864.

Thomas Green, from Fayette County, raised several companies of men that included Germans from Fayette and Washington Counties, who followed him to battles in New Mexico, Galveston, and the Red River Campaign in Northern Louisiana, where General Green was killed.

Waul's Legion organized in Washington County, had several completely German companies which served honorably at the Siege of Vicksburg.

In summary, the German immigrants thrust into an unwelcome situation followed their own individual conscience and did what each thought was the best way to protect their families in their new home.

The Biegel letter was previous published in full at www.fayettecountyhistory.org in a Footprints of Fayette column.

For a full length version of this story please contact the author at fayetteishome@gmail.com.

The Volunteer Aid Society

by Donna Green

When the War of Northern Aggression began in April, 1861, many citizens of Fayette County chose not to join with their fellow Southerners in fighting the invading Yankees.

However, many residents of the county threw down their plows, tossed aside their tools, gathered up their weapons and kissed their families goodbye as they rode off to fight for what they believed in.

When these men and young boys left to serve in the War Between the States, they left their wives and small children to take care of and maintain their businesses and farms.

Often this was too much work for the frail women and young children. Businesses and crops alike failed. Soon many of the families were unable to provide even the simplest of needs for themselves.

Consequently, many of these families began to suffer from lack of food and clothing.

In August, 1861 many of the more prominent members of the county came together to form a society specifically aimed at aiding these unfortunate people. The group took the name The Volunteer Aid Society. They began to advertise in the local paper, The States Rights Democrat, for new members. The group met at the courthouse for the very first time on Saturday, Sept. 7, 1861. According to the newspaper, the objective of the society was: “To make adequate provision for the support for the families of our volunteers as may be needed.”

In organizing a society such as this, the members were following the lead of many other counties in Texas in our area that had already established agencies for aiding the soldiers’ families. In their ad in the newspaper, they stated: “There is an abundance of corn and beef in this county. None need suffer.” Some of the more illustrious members of the society were: Judge Livingston Lindsay, who had a son-in-law, Benjamin Shropshire, fighting in the war; Granville J. Penn, who, himself was nearing the age of ninety; noted veteran of the Battle of San Jacinto, Joel W. Robison; General William G. Webb, who would himself eventually join the Confederate States Army; veteran of many early skirmishes and battles for Texas independence, John W. Dancy and newspaper publisher, Samuel McClellan, who would eventually gain notoriety as an outspoken critic of the war.

Yankees in La Grange

by Gary E. McKee

In 1864, two Yankee soldiers, named Wilbur Pelton and Aaron Sutton, escaped from the Confederate States of America's prisoner of war camp near Hempstead, Texas. Their objective was to get to Mexico, which they had been told, lay on the West Side of the Guadalupe River.

Traveling at night, they came upon the Colorado River, at the bend below the bluff in La Grange. There, they encountered a muddy bayou (Buckner's Creek) and decided to camp for a while to regain their strength. They knew a settlement was nearby, as they heard bells and saw cornfields. Pelton was becoming very sickly and this extended their stay. Needing food, Sutton foraged the surrounding farms and even made his way into the south side of La Grange.

After several days, Pelton died and Sutton dug a grave for his comrade, marking it by notching a tree and breaking off Pelton's knife blade in the notch.

Sutton then continued his escape towards Mexico, by "borrowing" a horse from a farm several miles west of La Grange. Some locals discovered him and the chase was on. After several hours, he managed to elude them after abandoning the horse. He continued his quest for freedom towards the Guadalupe River on foot, but fatigue, sickness and thirst got the best of him. Finding a house near Gonzales, he gave himself up to the mercy of a German family. They were sympathetic to him and nursed him back to health, but news reached the Confederates that a Yankee was in the area.

The German family had to turn Sutton into the authorities to protect themselves. Sutton was escorted back to the fairgrounds in La Grange. The Confederate Post, which was located in the southern part of La Grange, was manned by the home guard. Being the only prisoner, he was kept in a tent at night and allowed to walk around the encampment. Sutton requested permission to make and place a proper headstone over his friend's grave, near Buckner's Creek. He was granted permission, but most locals refused to believe that he had "lived" so close to them, without being detected. Some thought he would try escaping. He proved them wrong by leading the group to Pelton's grave.

After two weeks, his guards were going to escort him to Columbus. Prior to leaving, some German merchants, who were neutral in their North/South politics, donated a new set of clothes to replace the patched rags that Sutton had been living in. Eventually, Aaron Sutton was returned to the prison camp at Hempstead, where he once again escaped, this time making it to Union lines in Louisiana.

Source: Prisoner of the Rebels in Texas: The Civil War Narrative of Aaron T. Sutton, Corporal 83rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry. Decatur, IN: Americana Books, 1978.

La Grange After the Civil War

By Marie W. Watts

While Nathaniel W. Faison, a local entrepreneur and large landowner, was adding to his fortune by buying and selling land and cotton, the area around La Grange was suffering severely from the aftermath of the Civil War and Reconstruction. The local economy entered a precipitous decline as cotton plantations suffered from the loss of slave labor. The price of land in Fayette County dropped from $6.15 per acre in 1860 to $4.50 in 1866. Consumer prices nationwide—for bread, pork, beef, butter, rice, salt, coffee, tea, coal, and cotton goods—were 90 percent higher than before the war, but wages did not keep up, advancing nearly 60 percent.

In 1868 a distant relative of Faison, James A. Peden, who lived in a nearby county, wrote to his sister, “It is the hardest times in this county...that ever was seen. No crops, no business. Merchants failing every day and worst of all no money. I have owing to me three hundred dollars. And I would this night take twenty-five dollars for the whole.”

Newly freed African Americans had it no better; most ended up working on the land on shares, receiving one-third to one-half of the crop for their efforts.

Adding to the county’s woes, a yellow fever epidemic in 1867 crippled La Grange, killing 240 of its citizens; and in 1869 and 1870, the Colorado River overflowed, ruining crops.

The local government was in disarray. Governmental activities were overseen by the Fifth Military District, and county officers were often deposed by military orders, causing county officials to change routinely. This very unstable condition ushered in corrupt political conditions.

Lawlessness was rife in La Grange. A local woman wrote in her diary on May 15, 1865: “Soldiers, masked and with guns, entered the store of a German a few miles from here and took sixty to eighty dollars’ worth of goods. They threw down confederate bills for it, remarking that they were compelled to take dollar for dollar and he must.” James Peden wrote that “things are worse now than before the war. Bands of robbers infest the county. There is no law here nor at all. And advise all who think of coming to Texas to stay away...”

Sources:

F. Lotto, Fayette County, Her History and Her People (Schulenburg, Texas.: Sticker Steam Press, 1902). Lotto, 139.

Diary of Miss Phelps in An Early History of Fayette County, Wade and Weyand, 264.

Letter, James Peden to Bettie Peden, February 10, 1868.