Winchester

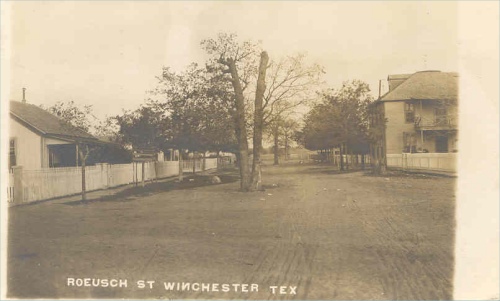

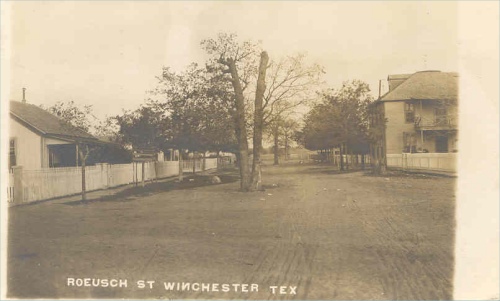

Winchester is situated in the northwestern part of Fayette county on the Waco branch of the San Antonio & Aransas Pass Railroad. It is about twenty miles distant from La Grange. The fertile Colorado River bottoms close by are tributary to its business. Part of the land is fertile mesquite prairie. There is also a great deal of postoak near Winchester. The Ingram prairie and the Cunningham prairie, the latter in Bastrop county, are in its neighborhood.

The teacher of the Winchester school is Miss Gillespie. Of lodges there are the Odd Fellows, Knights of Honor and Woodmen of the World.

is Miss Gillespie. Of lodges there are the Odd Fellows, Knights of Honor and Woodmen of the World.

The town has a Lutheran Church, Rev. A. L. Grasens, pastor; a Baptist Church, Rev. Duke, pastor; a Presbyterian Church, Rev J. W. Montgomery, pastor; and a Methodist Church, Rev. Calloway, pastor.

The town of Winchester was founded and laid off about the year 1857 by John Frame, who now lives in Falls county. It consists of seven general merchandise houses, one hotel, one butcher shop, two drugstores, two physicians, one saloon, one lumber yard, one blacksmith shop, one gin and one barbershop.

Of all the towns of Fayette county which are not incorporated Winchester does the largest business. It has become a lively town, due to the energy and business talent of her merchants, of whom Messrs. Sam F. Drake, W. A. Giles and E. Zilss may be mentioned as the most enterprising. Little & Mohler is the only saloon in the town; they are liberal and popular men and do as much business as any saloon in the county. Dr. A. F. Verderi is an old resident eminent physician of Winchester, who has effected a great many cures. [Note that all of the above purchased advertisements in Lotto's book.]

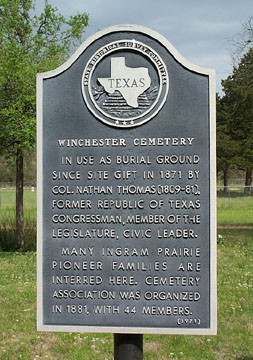

The settlement is one of the oldest in the whole county. As early as 1822 John Ingram, after whom Ingram's Prairie is named, came into that neighborhood and settled on the prairie. John C. Cunningham was another old settler of the Winchester neighborhood, but he settled in Bastrop county on the prairie named after him. The oldest settler of the Winchester neighborhood now living is A. D. Saunders. He has come there in the early forties and still remembers the last Indian raid in that neighborhood. Other prominent settlers are J. H. McCullom, Paul Haske, Dr. A. F. Verdery, G. C. Thomas, Mrs. James Young, Joseph Mohler, sr., Mrs. T. T. Parr.

The population of the settlement is largely American. Of late a great many Germans have come in. Winchester is a railroad station, postoffice and voting precinct of the county.

From Plantation Community to Boom Town and Bust

The African American Presence in Winchester, Texas

In a previous “Footprints” article that I wrote on the Catley Family of Winchester, Texas, I provided a history of the town, but primarily focused on one African American family. That article is online for anyone interested in reviewing it.

However, there is more to Winchester’s history, other than being one of the earlier settlements in Fayette County and the crossroads between Bastrop, Fayette and Lee Counties. The area also has had approximately 185 years of African American presence, which began in 1832 when John Ingram settled on a section of land, later known as Ingram’s Prairie, in the John F. Berry League in northwestern Fayette County with the intent to develop a cotton plantation. Winchester was founded about 20 years later when John Gromme platted the town and named it for Winchester, Tennessee, the birthplace of an early Anglo settler.

It is unknown exactly how many slaves Ingram owned up to1860, when a slave schedule shows that he owned twelve. However, after Ingram secured his land patent in 1827, surveyed his land and settled there in 1832, he helped coordinate a plantation community in the area. Plantations required a labor force to survive, so slaves were moved in from the southern states. That 1860 slave schedule also shows that other Winchester area plantation owners owned from eight to fifty-nine slaves. They pooled their resources to help one another and traded slaves back and forth for each other’s benefit.

Some of the leagues of land and plantations spanned from Fayette County into Bastrop County. The plantation community west of the Fayette County line in Bastrop County totaled over 13,000 acres; whereas, in Fayette County east of the Bastrop County line, there was a total of over 14,000 acres. This area of over 27,000 acres is one of the most fertile land masses in Texas, with the Colorado River as a major waterway, along with Pin Oak Creek, Little Pin Oak Creek and several sloughs and minor streams, all making it a perfect farming area that remains today.

Between 1832 and 1863, the combined plantation community grew at an astonishing rate as “cotton became king”. By 1860, slavery and tenant farming was in full force with several well-established plantations in the area, all of which contributed to the growth and prosperity of Winchester. Businesses eventually included a bank, physicians, druggists, mercantile stores, saloons, rooming houses, a hotel, blacksmiths and cotton gins, all built to provide for the needs of the people in the area.

When the Emancipation Proclamation became the law of the land in 1865, documentation of the actual percentage of African Americans became possible in subsequent census enumerations. Prior to this time, slaves were not identified by name, and many times were not enumerated at all. Thus, the 1870 U.S. Census reveals that the black population directly west of the Fayette County line in Bastrop County was 65 percent. The Winchester area directly east of the Bastrop County line and west of the town showed a similar percentage in black population. East of Winchester, the black population was almost 49 percent with the heaviest concentration being south of present-day FM 153 and east of the railroad tracks for approximately two miles. The combined total population, including all ethnic groups both east and west of Winchester, added up to 4,275 people feeding into the economic growth of the town in 1870.

At the end of the war, plantation owners in that area of Fayette County and extending into Bastrop County had an abundance of land to dispose of after they lost their labor force with the emancipation of their slaves. On the other hand, there was an abundance of ex-slaves with dreams of owning their own property.

Land ownership for the emancipated slaves was considered a way to achieve independence and the possibility of other rights. The skills that they had learned on plantations could also help sustain them on their own land. Instead, sharecropping left them with a life that was almost as difficult as slavery.

At the end of the Civil War, “forty acres and a mule” was a field order initiated by General William Tecumseh Sherman in January 1865 promising freed slaves a redistribution of confiscated property from Confederate plantation owners in southern states along the eastern coast. It was approved by President Lincoln a month later, but after his assassination in April 1865, his successor, Andrew Johnson, overruled the field order several months later, so the policy never became federal law. All the promised land was returned to the original owners. However, this concept of 40 acres, minus the mule, was utilized by plantation owners needing to sell their land. They decided that 40 acres would be a manageable size for each African American buyer, plus it would be adequate for self-sustainability. Loans were negotiated for the purchase of these tracts. If there was a default on the loan, the owner reclaimed and resold his land.

At the end of the Civil War, “forty acres and a mule” was a field order initiated by General William Tecumseh Sherman in January 1865 promising freed slaves a redistribution of confiscated property from Confederate plantation owners in southern states along the eastern coast. It was approved by President Lincoln a month later, but after his assassination in April 1865, his successor, Andrew Johnson, overruled the field order several months later, so the policy never became federal law. All the promised land was returned to the original owners. However, this concept of 40 acres, minus the mule, was utilized by plantation owners needing to sell their land. They decided that 40 acres would be a manageable size for each African American buyer, plus it would be adequate for self-sustainability. Loans were negotiated for the purchase of these tracts. If there was a default on the loan, the owner reclaimed and resold his land.

About 20 percent of the blacks in Texas did not choose an urban life and managed to avoid being sharecroppers by taking advantage of this offer to buy land. They then created their own autonomous agricultural communities, known as Freedom Colonies, where they could experience peace and security in a segregated American society. Family and friends could live next to one another in the same area, so that there was a sense of togetherness and familiarity. Many Freedom Colonies became self-sustainable with their own churches, schools and small businesses.

A large group of African Americans, who founded the Center Union Freedom Colony in Bastrop County, purchased 40-acre contiguous tracts in the J.C. Cunningham League, partly in Bastrop County and Fayette County, as well as in two other adjacent leagues in Bastrop County. The purchasing of 40 acre tracts continued from the Fayette County line north through half of the Charles Edwards League and east through part of the G.W. Whitesides League, comprising approximately 7,500 acres of family farms around Winchester.

Religion was of great importance to the African Americans as a source of hope in their world of drudgery. In addition, the gathering together for church services provided a time for social interaction and an exchange of news. The Shiloh Baptist Church, located one mile east of Winchester, had its beginning in 1867 in a brush arbor. However, due to a lack of black preachers and appropriate educational materials, it took five years for the church to be organized in 1872 with 180 members. Later, the Shiloh Methodist Church was also established, along with a school.

Despite the unsettled years after the Civil War, the African American population grew in Texas. In 1870, there were approximately 253,500 blacks or 30 percent of the total population of about 820,000. By 1880, there were almost 400,000 blacks. Migration into the state, as well as an increased birthrate among blacks, attributed to this growth. The increase in the African American population also affected Winchester’s growth.

To capitalize on potential business, more merchants began to set up shop in the area. One was the Goebel family, who opened a general store, cotton gin and lumber company midway between Winchester and the Center Union Freedom Colony. Their property was a little less than three miles west of Winchester along Pin Oak Creek and was split by the Fayette County and Bastrop County line. Opening a store at this location was a strategic move to capture business from both sides of Winchester, including the Center Union Freedom Colony and the Shiloh Community.

Because of the boom in the Winchester area from 1870 to 1920, many of the area African Americans, who had not taken advantage of the initial opportunity to purchase a 40-acre tract, had saved enough money by sharecropping or being tenant farmers to eventually buy land. Most of this group of African American landowners homesteaded along FM 153 east of the railroad tracks in Winchester. Some of the largest black landowners were Jerry McDow, John Johnson, Willis Taylor, Edward D. Threadgill, Charley Hart, George Ware and G.T. Ware. Other smaller landowners included W.L. Taylor, L. Oliver, W.H. Stevens, Rob Taylor, F. Moses. J.T. Duncan, E. Lucas, S. Parr, E. Penn, D. Jones and J. Starks, to name a few. All their tracts of land began on the east perimeter of the Shiloh Cemetery except for Charley Hart, whose acreage was a prime tract paralleling the east right-of-way of the San Antonio and Aransas Pass Railroad, with its south boundary being just north of Kaspar Street and south of the E. Winkler property.

The Edward D. Threadgill tract was directly across from the Shiloh Missionary Baptist Church and the former site of the Shiloh Methodist Church where their church bell monument now stands. The Coaxbury Elementary School, which served the black community from 1890 to 1948 when the Fayette County schools were consolidated, was located on Threadgill’s land.

The Jerry McDow and John Johnson tracts were split by present-day FM 153 and paralleled the west right-of-way of North and South Raymond Road. Some of the prominent African American landowners west of Winchester included E.J. Hart, King Bean, Nat Hardeman, Ruffin Hall, Ann Humphries, Ike Moten, Henry Davis, Mrs. Elizabeth Carr and Vastine T. Catley, the son of Jack Thompson Catley; Vastine lived with his family on the east side of Winchester on the McDow’s place prior to purchasing his own land and moving to the Center Union Freedom Colony.

The Jerry McDow and John Johnson tracts were split by present-day FM 153 and paralleled the west right-of-way of North and South Raymond Road. Some of the prominent African American landowners west of Winchester included E.J. Hart, King Bean, Nat Hardeman, Ruffin Hall, Ann Humphries, Ike Moten, Henry Davis, Mrs. Elizabeth Carr and Vastine T. Catley, the son of Jack Thompson Catley; Vastine lived with his family on the east side of Winchester on the McDow’s place prior to purchasing his own land and moving to the Center Union Freedom Colony.

The African American population remained almost constant in the Winchester area from 1870 to 1910 when the census for both years showed that 48 percent of the population was black. The school census for the school year 1918-1919 recorded for Winchester showed that 188 white and 193 Negro children attended school.

The Great Depression during the 1930s took its toll on everyone. Winchester was no exceptio—the Winchester State Bank failed, and other businesses were forced to close. By the 1950s, the original 40-acre tracts of land owned by African Americans had begun to change due to loss of ownership for not fulfilling tenant agreements, the lack of ability to pay taxes or bank loans, or being cheated out of the land. Many of these landowners were forced to seek their livelihoods in urban areas, thus decreasing the African American presence in Winchester. However, looking on the bright side, some of the original African American landowners still own their land, including the Catleys, Taylors, Partridges, Wormleys and Bledsoes.

The question remains—why did Winchester not continue to prosper as other cities did along the Colorado River, such as Austin, Bastrop, Smithville, La Grange and Columbus, Texas? There was a railroad that came through the town, as well as enough businesses to provide for the populace. Most likely, the major factors contributing to its demise were the Depression, the decline in cotton production and a significant decrease in the area’s rural population with the exit of large numbers of African Americans by the early 1950s.

Sources:

“African American History”. Handbook of Texas

Ancestry.com

Catley-Franklin, Della. Oral history

Fayette County and Bastrop County Appraisal District maps

Fayette County Map (original), re-published by General Land Office, 1978

Fayette County Slave Record for 1860

Fayette County, Texas Heritage, Vol. 1; Curtis Media, 1996

“Forty Acres and a Mule”; blackpast.org

Edgar Tobin Oil Map of landowners in Fayette and Bastrop Counties

Lotto, F. Fayette County Her History and Her People; 1902

Smith, Dr. Starita. “Emancipation means Migration”, Prairie View A&M University; online newsletter

Photo captions:

Top: Cotton pickers in the Winchester area; photo courtesy of Della Catley-Franklin

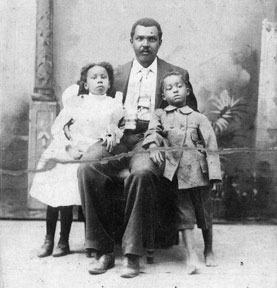

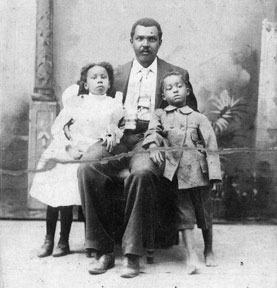

Bottom: Jack Thompson Catley Family: Emma, Jack, Vastine; photo courtesy of Della Catley-Franklin

is Miss Gillespie. Of lodges there are the Odd Fellows, Knights of Honor and Woodmen of the World.

is Miss Gillespie. Of lodges there are the Odd Fellows, Knights of Honor and Woodmen of the World. At the end of the Civil War, “forty acres and a mule” was a field order initiated by General William Tecumseh Sherman in January 1865 promising freed slaves a redistribution of confiscated property from Confederate plantation owners in southern states along the eastern coast. It was approved by President Lincoln a month later, but after his assassination in April 1865, his successor, Andrew Johnson, overruled the field order several months later, so the policy never became federal law. All the promised land was returned to the original owners. However, this concept of 40 acres, minus the mule, was utilized by plantation owners needing to sell their land. They decided that 40 acres would be a manageable size for each African American buyer, plus it would be adequate for self-sustainability. Loans were negotiated for the purchase of these tracts. If there was a default on the loan, the owner reclaimed and resold his land.

At the end of the Civil War, “forty acres and a mule” was a field order initiated by General William Tecumseh Sherman in January 1865 promising freed slaves a redistribution of confiscated property from Confederate plantation owners in southern states along the eastern coast. It was approved by President Lincoln a month later, but after his assassination in April 1865, his successor, Andrew Johnson, overruled the field order several months later, so the policy never became federal law. All the promised land was returned to the original owners. However, this concept of 40 acres, minus the mule, was utilized by plantation owners needing to sell their land. They decided that 40 acres would be a manageable size for each African American buyer, plus it would be adequate for self-sustainability. Loans were negotiated for the purchase of these tracts. If there was a default on the loan, the owner reclaimed and resold his land.  The Jerry McDow and John Johnson tracts were split by present-day FM 153 and paralleled the west right-of-way of North and South Raymond Road. Some of the prominent African American landowners west of Winchester included E.J. Hart, King Bean, Nat Hardeman, Ruffin Hall, Ann Humphries, Ike Moten, Henry Davis, Mrs. Elizabeth Carr and Vastine T. Catley, the son of Jack Thompson Catley; Vastine lived with his family on the east side of Winchester on the McDow’s place prior to purchasing his own land and moving to the Center Union Freedom Colony.

The Jerry McDow and John Johnson tracts were split by present-day FM 153 and paralleled the west right-of-way of North and South Raymond Road. Some of the prominent African American landowners west of Winchester included E.J. Hart, King Bean, Nat Hardeman, Ruffin Hall, Ann Humphries, Ike Moten, Henry Davis, Mrs. Elizabeth Carr and Vastine T. Catley, the son of Jack Thompson Catley; Vastine lived with his family on the east side of Winchester on the McDow’s place prior to purchasing his own land and moving to the Center Union Freedom Colony.