Monument Hill

BURIAL SITE OF DAWSON & MIER CASUALTIES

LA GRANGE, FAYETTE COUNTY, TEXAS

Footprints of Fayette Articles

These brief histories were written by members of the Fayette County Historical Commission. They first appeared in the weekly column, "Footprints of Fayette," which is published in the Fayette County Record, Banner Press, Flatonia Argus, Schulenburg Sticker, and Weimar Mercury newspapers. A new article appears weekly. See index of all Footprints of Fayette articles.

Monument Hill

By Gary E. McKee

On a high bluff overlooking the Colorado River bottom in La Grange, Texas stands a tall limestone shaft. At the base of the shaft is a gray granite crypt containing the remains of heroes of the Republic of Texas. The following is the story of how this beautiful oak covered promontory came to be a shrine to freedom.

On a high bluff overlooking the Colorado River bottom in La Grange, Texas stands a tall limestone shaft. At the base of the shaft is a gray granite crypt containing the remains of heroes of the Republic of Texas. The following is the story of how this beautiful oak covered promontory came to be a shrine to freedom.

Twas six years since the smoke from the funeral pyre of the men of the Alamo had darkened the sky over the town of Bexar. Mexico still refused to recognize the independence of the land north of the Rio Grande.

In September of 1842, the Mexican government sent another wall of eagles and serpents sweeping into Texas to reinforce their claim. The force surrounded Bexar, making surrender the only viable option for the Texian officials holding court in the town later to be known as San Antonio.

When the news of the Mexican invasion reached the town of La Grange in Fayette County, the local militia, led by Nicholas Dawson, mustered under the oak tree on the town square. About fifteen men left the square on horseback and crossed the Colorado riding towards Bexar. Along the way, Dawson enlisted men until a total of fifty-three men arrived at Salado Creek a few miles northeast of the Alamo.

Dawson’s party had traveled one hundred miles in just under two days, quite a feat at that time. Their horses were exhausted and the men had dismounted to prepare for battle. A Mexican patrol discovered Dawson, split into two pincers and surrounded the small band of Texians. At the center of the Mexican force were two cannon loaded with grape and canister shot. As Mexican lead poured into the Texians, more than half their number fell in the first few minutes. Seeing only two choices, death or surrender, Dawson surrendered. The silence of death and the cries of the men on the verge of death filled the air. The dead thirty-eight Texian heroes were left for the scavengers as the Mexican army headed back to the border. Fifteen men from Dawson’s command and the captives from Bexar courtroom were with them.

Other companies of militia from Fayette County arrived too late to assist Dawson. Captain William M. Eastland, Dawson’s cousin, commanded one of the militia units. The dead were buried on the banks of the Salado where they had fallen. The militia units returned to their homes to mourn their dead and plan their revenge.

Retribution began in November of 1842, when a group of 750 men left Bexar to avenge the death of their neighbors and relatives. Freezing weather, desertion, and the sacking of Laredo by the Texian force soon forced the Texian commander to order a return to Bexar and disband. Those still seeking revenge elected officers who wished to carry on.

On Christmas Day, a force of 261 men crossed the Rio Grande and attacked the town of Mier. Once again, a larger Mexican force surrounded the town, causing the Texians to surrender, mistakenly figuring they would be treated as prisoners of war and released. The Mexican government viewed the Texians as a band of rebels, and it was decided to march the able bodied prisoners deep into Mexico and imprison them.

Enroute, the Texians made numerous plans to escape that culminated in a mass breakout at the Hacienda Salado on February 11, 1843. After escaping the Hacienda, the Texians then broke into groups trying to return to Texas. The harsh terrain caused the majority to be recaptured. Three men managed to walk the three hundred mile trip to Texas. Two of these men were Fayette County men.

To teach the unruly Texian rebels a lesson, President Santa Anna ordered that the men be decimated. Decimation, a Latin word meaning to select one out of ten, has been used by armies since the time of Julius Caesar. One tenth of the 176 Texian rebels would be executed by firing squad.

A death lottery was organized, and an earthen jar was filled with one hundred fifty nine white beans and seventeen black beans. The prisoners were lined up to draw their own fate. Drawing a black bean meant death. All the officers drew first, and all drew a white bean with the exception of Captain Eastland, Dawson’s cousin from La Grange. The Captain was the first man to draw a black bean.

The enlisted men then drew the rest of the beans. The executions were carried out with full military ceremony. The bodies were left in a pile for four days before being moved to the nearest cemetery in the town of Cedral.

The surviving prisoners of what became known as the Mier Expedition were marched to Perote Prison near Mexico City where they met the Bexar/Dawson prisoners that were still alive. Utilizing various methods such as escape, bribery, foreign intervention, death and the “generosity” of Santa Anna, all of the men had left Perote Prison by September 16, 1844 and returned north of the Rio Grande.

After the annexation of Texas by the United States, a border dispute triggered the Mexican-American War. The Texians once again had their opportunity to seek revenge upon Mexico. Hundreds of Texians volunteered for service in the American army.

After the American invasion force had pacified the Mexican Army, a regiment of Texian Rangers under Major Walter P. Lane were stationed near Hacienda Salado and the town of Cedral. One of the Mier Expedition survivors, Captain Dusenberry asked permission to take a detail into Cedral and retrieve the bones of his comrades. Lane could not officially authorize such a violation of the truce; he just merely ignored the request.

A troop of Texians left under the cover of darkness with at least three Fayette County men in the small troop. They brazenly entered the town and impressed several “volunteers” to commence digging in the graveyard under the complaints of the priest. The bones were excavated and packed into four boxes and strapped to mules. By this time, the Mexican cavalry had been alerted and the Texians beat a hasty retreat back to their lines with a Mexican patrol in pursuit.

The boxes were returned to Texas and stored in the Fayette County courthouse. La Grange was chosen as the final resting place of the Mier men, to honor the only officer and first man to draw a black bean which sealed his fate, Captain William Mosby Eastland.

The return of the remains galvanized the community to retrieve the bones of Dawson’s men and a citizens’ group brought the bleached bones back to La Grange from the banks of the Salado. Veterans and citizens held meetings and decided to entomb the men on the commanding bluff to the south of La Grange. On September 18, 1848, a somber procession left the town square where six years before, Nicholas Dawson had hastily assembled a squad of men to protect their families and rode off into history. A befitting ceremony was held with proper respect being rendered.

At first, a simple sandstone vault was the tomb of these patriots. A committee was organized to raise money for a more befitting monument. The Monumental Committee decided upon starting a newspaper to fund a proper monument.

The paper existed for four years during which its purpose shifted from funding a monument to the Dawson and Mier men, to a monument to all Texas heroes to establishing a “Monumental College”. The Texas Monument paper failed because in the hope of attracting money, its editorial policy limited news that would not offend any potential donor.

So the heroes of Texas remained in their crude sandstone crypt on the bluff overlooking La Grange.

When the decision to bury the men on the bluff was made, the burial plot was on a league granted in1832 to David Berry. David Berry was over seventy years old when he joined Dawson’s band and was killed at Salado Creek. The land went through several owners. When H.L. Kreische purchased the land, the burial plot was not reserved on the deed. In 1850, to correct the oversight he offered to sell 10 acres surrounding the tomb under certain conditions to which the Monumental Committee consented. The conditions being that when a cornerstone was laid, he would be paid one hundred dollars. However, if nothing occurred in fifteen years the deed was null and void. The Monumental Committee folded and in1857, Kreische built his house adjacent to the tomb and claimed the land in 1865.

In 1904, the Kreische descendants, tired of unfulfilled promises by numerous groups to maintain the crypt, demanded the removal of the vault and its contents. They supposedly threatened to throw the remains over the bluff into the river if action wasn’t taken quickly. This drastic measure prompted the Daughters of the Republic of Texas chapter in La Grange to contact the state government and the land was purchased for $350.

In the early 1930s, when a state official visited the site with the purpose of moving the remains to the new state cemetery in Austin, it was surrounded by a rusty, neglected barbed wire fence. A tree growing out of the side floor of the tomb with cactus and other plants growing indiscriminately around it showed the neglect. Before leaving La Grange, the official mentioned that the remains were to be relocated to Austin.

This announcement spurred the creation of the Monument Hill Memorial Association. When the state returned to begin the move it found that “the ground around the vault cleared off clean as a whistle...the cracked walls repaired and an iron fence with a concrete curb erected around it.” Within two months a fitting granite cover was built over the old sandstone tomb. The 1936 Centennial was a boon for Texas history as the state spent large amounts of money to honor and preserve its heritage. Ten thousand dollars was appropriated for a monument to be placed next to the tomb. The forty foot shaft with the bronze angel at the base was soon completed on the small plot.

This announcement spurred the creation of the Monument Hill Memorial Association. When the state returned to begin the move it found that “the ground around the vault cleared off clean as a whistle...the cracked walls repaired and an iron fence with a concrete curb erected around it.” Within two months a fitting granite cover was built over the old sandstone tomb. The 1936 Centennial was a boon for Texas history as the state spent large amounts of money to honor and preserve its heritage. Ten thousand dollars was appropriated for a monument to be placed next to the tomb. The forty foot shaft with the bronze angel at the base was soon completed on the small plot.

In 1957, Fayette County residents raised money to purchase the 3.54 acres around the tomb and donated the land to Texas Parks and Wildlife Department to use as a state park.

Today, Monument Hill-Kreische Brewery State Historical Site contains the tomb, monument, and a historically accurate mural of the execution of the Mier men.

Nathaniel W. Faison and Perote Prison

By Marie W. Watts

Nathaniel W. Faison was one of the lucky ones who survived the Dawson Massacre on September 18, 1842. However, his ordeal was just beginning. He and the other survivors were marched approximately 1,000 miles to Perote prison in southeast Mexico. They marched 15 to 42 miles a day, arriving at Perote on December 22, 1842. Many of them suffered from the cold, having only clothing suitable for September weather.

Nathaniel W. Faison was one of the lucky ones who survived the Dawson Massacre on September 18, 1842. However, his ordeal was just beginning. He and the other survivors were marched approximately 1,000 miles to Perote prison in southeast Mexico. They marched 15 to 42 miles a day, arriving at Perote on December 22, 1842. Many of them suffered from the cold, having only clothing suitable for September weather.

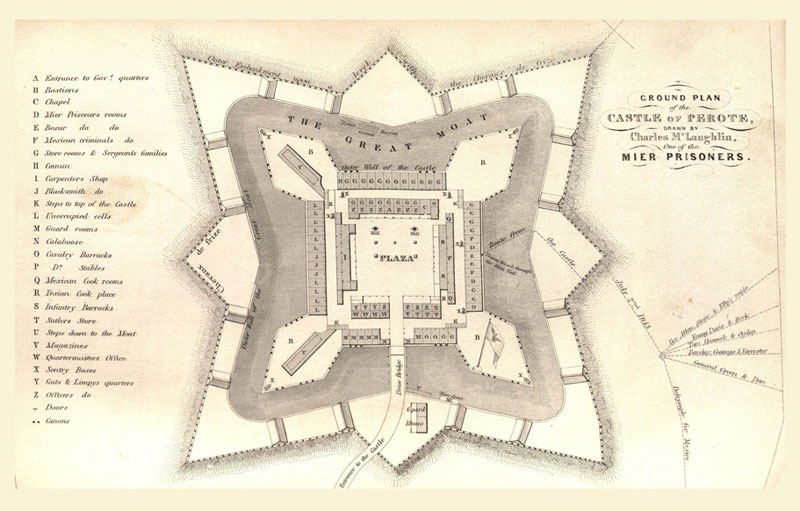

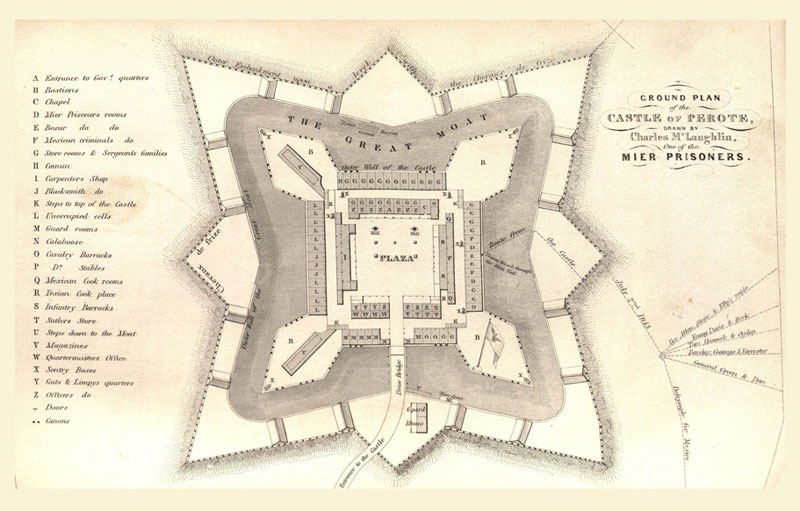

Perote, in the Mexican state of Vera Cruz, was built over a seven-year period in the 1770s by the Spanish authorities in Mexico to guard one of their main trade routes and to serve as a depository for treasure awaiting shipment to Spain. The stone fortress, covering an estimated 26 acres and surrounded by a moat, was used by the Mexican government as a prison. The cells in which the prisoners were housed were long and narrow (20 feet by 70 feet) with low, arched ceilings. A shaft on the wall opened to the elements, telescoped through the 8-foot-thick wall from a 2-foot square inside the room to a to 4 by 12 inch opening outside. The floors were rough concrete. Because the winters were cold and rainy, a damp chill permeated the cells.

The Texians were tormented by bedbugs, lice and fleas. Faison and others spent time daily delousing themselves. Finally, after the Mier prisoners arrived, the men were taken periodically to bathe in the foul waters of the moat.

Four days after their arrival, the prisoners were chained together with an 8-foot chain weighing approximately 20 pounds. Faison and fellow Dawson survivor, Edward Manton, lived this way for seven months and, according to Manton, the two never exchanged a cross word. They were separated when Faison went to work in the carpenter shop. Manton was optimistic that he and his new partner could get along equally well.

Despite these hardships, prisoners were allowed to communicate with friends, receive money and gifts, and purchase supplies outside Perote Castle. Manton reported that there was a store in the prison where those who had money could buy extra food and other items.

Richard Barkley of the Dawson Expedition wrote home to say that his daily rations consisted of six ounces of bread, a half pint of corn meal coffee, a small quantity of potatoes badly sprouted, and a small quantity of rice.

According to Barkley, the Mexicans called him the worst prisoner in the castle. He was hobbled for two weeks, beat with spades and muskets, and “Calaboosed”. The longer Barkley was there, the worse he was treated; his work load doubled.

Desperate, Barkley planned an escape, only to be stopped by his fellow prisoners. They felt his departure would cause the Mexicans to treat the remaining prisoners badly. Barkley even complained that the prisoners from San Antonio treated him poorly. Finally, Barkley escaped on July 2, 1843 along with David Smith Kornegay and others.

Dawson Expedition member, Norman Woods, on the other hand, saw it differently. He reported that there was plenty to eat and good clothes to wear. He was served coffee twice a day, had good flour bread, and was given meat daily. Like all carpenters and tradesmen, he worked for 25 cents a day.

Faison did not appear to suffer as Barkley had. On December 24, 1843 Faison wrote the following letter to his father from Perote:

Dear Father:

I wrote to you about the first of June and stated that I expected to be liberated from my imprisonment on the 15th of that month. We were assured by the English and American consols (sic) that Santa Anna promised them to do so but instead of being at liberty we are still detained here as prisoners of war, where we have been for upwards of twelve months and how much longer we are to be kept here time only can tell, but from the negotiations going on between Texas and Mexico it is to be hoped that we will not be detailed a great deal longer. I have enjoyed good health since I was taken, until about four weeks ago when I had a severe attack of fever and am just recovering. The same kind of fever has been among us for about five or six weeks, and has swept off some 12 or 15 of our members, which was about 175. We are all as well treated as could be expected of from the hands of the people we are in. We are kept chained and made work. Our rations are coffee, bread and rice. A week ago was pleased that my affairs in Texas are well attended to by S.S. B. Fields, a friend of mine. Tom is hired at $10 a month to a very good man.

Many of our Company who have received no assistance since they were prisoners are almost entirely without clothing, many are barefooted. There are more than fifty who have not a shirt to their name. I should have been in the same situation had it not been for 25 dollars which I borrowed of a young man who received money from the U.S. but I am now out of money and am getting rather destitute of comfortable clothing.

When you write to me which I am in hopes will be as soon as you get this, pay the postage to New Orleans and direct the letter to me at Perate (sic), to the care of

T.M. Diamond, American consul, Vera Cruz.

I have nothing more to write you at present, but will give you a full history of my trip when I get out of this trap. Remember me to mother and all the children and accept for yourself my highest regards.

N.W. Faison

P.S. Write to me every month or two until you hear that I am at liberty.

In fact, a typhus epidemic swept through the Perote prison that fall. The disease is a bacterial infection spread by bites from body lice and rat fleas. Scratching the bites opens the skin, allowing greater access of the bacteria into the bloodstream. Initially, there are flu-like symptoms, including a severe headache, high fever, chills, dry cough, muscle and joint pain, followed by a rash, delirium and a coma.

In fact, a typhus epidemic swept through the Perote prison that fall. The disease is a bacterial infection spread by bites from body lice and rat fleas. Scratching the bites opens the skin, allowing greater access of the bacteria into the bloodstream. Initially, there are flu-like symptoms, including a severe headache, high fever, chills, dry cough, muscle and joint pain, followed by a rash, delirium and a coma.

The Mexicans attempted to treat the prisoners in a hospital at Perote. However, because as many as 86 of the prisoners had become ill, another hospital was opened in the nearby town. Norman Woods and two of Faison’s other comrades in arms succumbed to the deadly disease and were buried at the prison.

The Texas Congress made appropriations for the relief of the men at Perote. However, the prisoners never received the promised aid. Many began to feel that their country was forsaking them and blamed President Sam Houston for their dilemma.

By March 21, 1844 the local newspaper, the La Grange Intelligencer, was desperate to secure help for the Perote prisoners; asking the public to donate money to those in need. An article described the beef that was given to the prisoners as being diseased. The animals were so feeble, the paper claimed, that they had to be carried in. Some of the cattle were snake bitten and, when killed, had less than a pint of blood because most of the blood had turned to a yellow water.

The newspaper also alleged that, when beef was occasionally served, the Texians were only allowed 3 to 6 ounces. The serving included bones and entrails; only the horns and hooves were excluded.

Other food, the Intelligencer charged, was equally nauseating. Beans were frequently rotten and the rice stinking. Coffee was mostly manufactured out of old, dried-up corn, burnt tortillas, sword beans, and other ingredients.

Fortunately for Faison, his ordeal came to an end on March 23, 1844, when he was released along with about 34 other prisoners. Before he could leave, he had to take an oath that he would not again bear arms in the contest between Texas and Mexico. He and his fellow prisoners set sail from Vera Cruz on the Brig Bainbridge on April 1, 1844, first going to New Orleans, Louisiana and then home.

To celebrate the prisoners’ return, La Grange threw a ball; the fashionable of both sexes were in attendance. They danced to violin music as the honorees enjoyed their liberty. The Intelligencer exclaimed that there has been no party in history to surpass it. In addition, the grateful prisoners sent a letter of thanks to General Waddy Thompson, United States Consular-General, who negotiated their freedom.

No records have been uncovered to indicate that Faison ever took up arms again. Despite his service to the Republic, the locals apparently did not view him kindly. By 1934, Houston Wade, a local historian, had this to say: “Whatever else Mr. Faison might have been, we have located a claim which shows that he was a good business man and did not propose to spend over a year and a half in a Mexican prison without making Texas pay him for it if he could.” Wade reproduced Faison’s request to the State of Texas dated June 25, 1850 in which he requested a payment of $497.75 ($13,956.72 in 2014 dollars) to cover his imprisonment and loss of his horse and equipment.

Photo captions:

Top:

Mier prisoners escaping from Perote; courtesy of Texas State Library Archives Commission

Lower: Ground Plan of the Castle of Perote drawn by Charles McLaughlin, one of the Mier prisoners; courtesy of Texas State Library and Archives Commission.

Sources:

Connor, Seymour V. "Perote Prison," Handbook of Texas Online published by the Texas State Historical Association, (http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/jjp02), accessed January 04, 2016.

Cutrer, Thomas W. "Dawson Massacre," Handbook of Texas Online published by the Texas State Historical Association. (http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/qfd01), accessed October 25, 2015.

Krenek, Dr. Harry, L. Death in Every Shape: The Dawson Massacre and the Men of Fayette County, Rockport, Texas: American Binding and Publishing Company, 2003.

La Grange Intelligencer; La Grange, Texas, March 21 & May 2, 1844.

‘Typhus’ downloaded from http://www.medbullets.com on October 25, 2017.

Wade, Houston. “The Dawson Men of Fayette County”; The La Grange Journal, July 19, 1934.

Black Beans of Death

by Carolyn Heinsohn

The following article by an unknown author was published in The La Grange Journal on November 15, 1928. In addition to a descriptive account of the massacre of the seventeen Mier prisoners who drew black beans at Salado, Mexico, the article also includes a first-person account by Franciska Willrich Vogt, who at age 13 witnessed the burial of their remains in 1848 on the bluff south of La Grange.

It is a cold, gloomy day in March of 1843. A dismal wind startles weird echoes in the trees and canons of mountainous country near Salado, Mexico—rising in the mountains and sweeping with vicious insistence down to the little settlement where one hundred and seventy-six men are doomed to die.

In their hearts there is little hope of release. They sit in the stifling air of a rude shed, converted into a death chamber from a barn, and wait orders to march before a firing line and surrender their lives for Texas. Awaiting the surrender of their all—these who had scorned all other surrender as not befitting men who had sworn themselves to win freedom for their state.

Their clothes were worn threadbare, their feet were sore and lacerated from those long days and nights on the mountains without food or shelter while they sought the way back to Texas. Bodies were weak and helpless from the long exposure and in their minds was no thought but the release death would bring. In the hands of the Mexican general Santa Anna they hoped for no mercy.

Guards enter the room and silently place the men in heavy iron chains, ordering each to stand in line as he was bound. No word is said—then one of the Mexicans holds an official looking document to the light and reads orders that chill the blood of every man who heard them. They had expected death—death for them all according to the will of Santa Anna. Their capturer, General Mexia, had written his relentless commander, asking freedom for the prisoners, and Santa Anna had granted that only one man out of every ten would be shot and that the others might be spared.

In the history of Texas is written many chapters of dramatic happenings, but none more powerful in ironic twists of fate than the scene that followed the reading of the cruel orders.

An officer, holding an earthen mug in his hand, comes into the shed where the Texans were confined and bound in chains. In the mug were one hundred and seventy-six beans, the number of the prisoners. One hundred and fifty-nine beans were white and seventeen were black. The prisoners were each to draw a bean from the mug. The black beans meant death.

To tell the rest would be only to repeat a story known to all Texans, for the destiny of the Mier prisoners—men who dared to enter the enemy’s country out-numbered many times, to save their comrades captured by General Woll at San Antonio—will be retold and remembered through many generations.

It is from the lips of Mrs. Franciska Vogt of La Grange that the story was recently recounted with a new and gripping angle on the well known incidents—for Mrs. Vogt is the one person living who was present and remembers when the bones of these seventeen men were brought back to Texas soil and buried on the bluff overlooking her home in La Grange. And it was on her 93rd birthday that she recalled that solemn ceremony of 1848, when as a child of 13 she rode bareback to the site where the Mier prisoners were re-buried with honor and praise.

“Ah, I shall never forget how it looked— that procession of men riding mules and leading others with the bones of the Texans slung in gunny-sacks across the backs of the animals,” she said, her eyes once more glowing with the amazement she must have felt as a child. “They came right into town, and when I heard what was going to be done, I remember I ran and jumped on my pony and raced to the top of the hill for the ceremony.”

“I do not remember much of what happened, except that it was all very solemn and quiet as the bones were carefully and tenderly buried up there on the hill. Then the monument was put up—the big limestone tomb under which are the remains of those seventeen men who drew the black beans of death.”

Mrs. Vogt recalled that she was unable to get astride her horse after it was all over – remembering, as she says, more of the smaller details that made an impression on a young mind.

“I know it was some man from Austin who helped me – some nice man who held my horse and helped me swing up to ride back home again, but I do not know who, though I still remember how he looked that day,” she said.

The little old lady who will soon reach the century mark also told the story of the man who took the black bean drawn by a comrade away from him and died in his stead. The incident may be legend or true, but Mrs. Vogt states that she has heard it all her life and believes its veracity. It is told that the first to draw the fatal lot was a man with a wife and children back at home, and that his friend forced him to exchange the beans so that he might live.

Though the names of this Damon and Pythias of Texas history may be lost in the maze of years, what a monument to friendships that face life and death with equal unselfishness!

The burial of the Mier prisoners is only one of the incidents of early Texas history that can be told in the first person by the gray-haired and smiling grandmother and great-grandmother of La Grange. She came to Fayette County from Germany in 1847 with her mother and brothers and sisters, following the father George Willrich, who had come the previous year and located a home. Mrs. Vogt tells that the state gave 300 acres of land to every man with a family who settled in that country then – land as wild as if it had never been touched by man.

“These hills were thick with wild animals and rattle snakes, but I got used to them and remember riding all over the country by myself as a child,” she relates. “I will always remember one time when I was going after the horses for my mother and came up on a lot of commotion in the woods. When I got to a clearing, I saw six wolves tearing at the body of a deer they had killed.”

Mrs. Vogt’s father was a prominent judge in the “old country,” and came to America with many other immigrants during those years who sought freedom and prosperity in the new land. He had a large family of children whose children and children’s children are numbered among the settlers of the state. Mrs. Vogt’s own children are Mrs. Ernest Knigge of La Grange, with whom she makes her home; E. R. Vogt of Schulenburg, Julius Vogt of O’Quinn, Mrs. Fritz Nollkamper, Fritz Vogt, La Grange.

The story of the Mier prisoners will again be placed before the people of Texas during the next legislature, it was recently learned, as the senator and representative from that part of the state, Senator Gus. Rusek of Schulenburg and Rep. James Pavlica of Flatonia, are to ask that 50 acres of land along the top of the bluff where the men are buried, be purchased by the state for a state park and a memorial to their heroism. The land is available for purchase at this time, and as the location is ideal scenically for a beautiful recreation resort, they will use all their power to pass the bill creating the Mier park for Texas.

A monument already stands on the court house square at La Grange, erected several years ago by the state “to the memory of the men who drew the black beans and were shot at Salado, Mexico, on March 24th, 1843,” and to Capt. N. H. Dawson and his men who were massacred at Salado, Texas, in September of 1842. The remains of some of these men are also said to rest with the Mier prisoners in the tomb at La Grange, brought back by the group who went by mule train on their errand of such grim homage.

To follow the trail of these one hundred and fifty-six men who were spared in the fatal lottery at the haciendo of Salado would be to wonder whether or not the man who saved his friend did not leave him the worse fate. Dying of unbearable hardships on their march into Mexico City, wasting away in dungeons, shot while trying to escape and a few finally winning their way back to Texas, the group one by one went the way of their comrades who drew death from the glass of chance that day. But no matter what followed for them, it would surely be safe to imagine that none experienced deeper agony of suspense, or grief for his comrades, than when they plunged their hands into the little grains of matter, colored black and white, that meant a promised freedom or a black doom.

Bones Back to La Grange

by Richard Tinsley

During the Mexican War in 1848, and five years after the Mier men had been decimated, an armistice was agreed upon between the two competing armies.The American Army was at Concepcion, the most advanced post of the army, and twenty men of General Walter P. Lane's command, knowing they were only about fifty leagues (about 150 miles) from the Hacienda de Salado, where on March 24, 1843, the Mier prisoners had been decimated, resolved to make the effort to exhume their remains and bring them to their own country. Five of the men drew white beans at El Salado, and John Dusenberry and James Sealy, who were two of the five, remembered the exact spot where their comrades had been buried. By forced marches they reached the spot, but the priests of the village and other important dignitaries bitterly opposed their removal, but finally the Texans carried their point. On reaching the spot they found a cross had been erected over their graves, and the ground had been consecrated.

A kind hearted Mexican woman kept the grave and the cross with flowers, and there they knelt and made their devotions. When the earth was removed and the cross fell, the cry of "Por Dios" or "Oh! God!" went around the circle, The remains, even to the smallest bone, were placed in sacks, put upon pack horses and by forced marches, they safely reached Concepcion. General Woll, the American commander, made the offer of free transportation to Galveston, and Mr. Dusenberry reached La Grange, Texas, in June 1848, this having been the place decided upon by the Americans for their final resting place. On September 18th of the same year, the Dawson men who had fallen in the fight at Salado Creek, six miles southeast of San Antonio, whose remains had been disinterred, were reinterred with the Mier men and now rest on Monument Hill in La Grange. A monument was erected to them at that place and the State of Texas also erected another, which stands in the courthouse yard, on which are inscriptions telling of their brave and heroic deeds.

List of Texans decimated at El Salado March 25, 1849: L.L. Cash, James D. Cocke. Capt. Wm. Eastland, who went from La Grange, Edward Este, Robert Harris, Thos. L. Jones, Patrick Mahan, James Ogden, Charles Roberts, William Rowan, J.L. Sheppard, J.M.N. Thompson, James N. Torrey, Humboldt James, Henry Whaling, M.C. Wing, making seventeen in all.

From The Boy Captive, pp. 323-324, by Fanny Chambers Gooch-Iglehart Bones Iglehart

Fayette County Historical Commission editors note: There at least two published versions of the return of the remains of the decimated men on the Mier Expedition. While the recollections vary widely on the specifics of the retrieval and the truth lies somewhere in between, the respect and courage of John Dusenberry and his men demonstrated by returning their fallen comrade's remains to their families is heroism to its highest degree.

The Tomb of Texas Heroes

By Charles Hebert

On April 25, 1846, a skirmish between Mexican Cavalry and U.S. Dragoons at Resaca de la Palmas near Brownsville, Texas brought Texas and The United States on a full-fledged war footing with Mexico. A U.S. Army officer sent an urgent telegram to Washington informing President Polk that “American Blood had been spilled on American soil.” The U.S. declared war. Texans rallied to the cause as white bean survivor Jon Dusenbury and hundreds of other Texans joined the First and Second Texas Rifles of The Texas Rangers. Dusenbury was made a Captain of the forward guerilla fighters and scouts under the command of Major Walter Paye Lane, whose immediate commander was Captain Jack Hays.

In early May 1847, General J.E. Wool ordered Major Lane to take his entire regiment, some 420 horsemen in all, to escort Army Captain John Pope, a topographical engineer, on a reconnaissance mission to scout the town of San Luis Potosi 80 miles south, where the Mier prisoners had met their fate at nearby Hacienda Salado on March 25, 1843. Seventeen prisoners were executed there by order of Mexican General Santa Anna. Instead, Lane offered a counter proposal to General Wool, asking that he be allowed to hand pick 40 men and their horses from his own command to go on the scouting mission. Wool reluctantly agreed to the request, as did Captain Pope, with the provision that “no unnecessary contact would be made with any civilian or military units that would jeopardize the mission”. During the evening of May 2, 1847, Captain Dusenbury, commanding officer of the Texas Rangers, approached Captain Lane asking for permission to allow a group of Rangers to ride into the town and exhume the bodies of the slain Mier prisoners. Permission was granted, and the Rangers rode into town at 3 a.m. on the morning of May 3, 1847; they grabbed the mayor out of his bed as a hostage, rounded up a Catholic priest, along with a five man work crew, and exhumed 16 sets of bones of the original 17 from the ditch in which they were buried. All the bones were placed in tightly tied sacks, each bag containing only one body. The bundles were then placed into four large boxes that were strapped on two mules with each mule holding two boxes. Hours later, the Rangers left town on a hard 80-mile ride back to their own lines.

The bones traveled with General Zachary Taylor’s personal baggage until the U.S. Army secured passage for Dusenbury from the Mexican coast to Galveston where Dusenbury secured wagons bound for La Grange. Since La Grange was the home of Captain William Mosby Eastland, the senior ranking black bean victim, the town was chosen for the burial site. Dusenbury entrusted the remains of the black bean victims to the citizens of Fayette County on May 29, 1847. The bones were kept temporarily in the county courthouse in preparation for burial.

However, the remains of the Dawson men still had to be retrieved. A county-wide meeting was held on the square in La Grange, and men from throughout the county were delegated to exhume the remains from the massacre at Salado Creek outside of San Antonio and return them to Fayette County for reburial. Once accomplished, the remains were placed in two coffins; one for the Dawson men and the other for the victims of the Black Bean Incident. Arrangements were made with George Willrich, the land owner on the bluff, to bury these men on his property on the heights south of La Grange. Willrich had purchased the land from David Berry, who at 70 years old was killed in The Dawson Massacre, thus returning him to the land that he originally owned.

However, the remains of the Dawson men still had to be retrieved. A county-wide meeting was held on the square in La Grange, and men from throughout the county were delegated to exhume the remains from the massacre at Salado Creek outside of San Antonio and return them to Fayette County for reburial. Once accomplished, the remains were placed in two coffins; one for the Dawson men and the other for the victims of the Black Bean Incident. Arrangements were made with George Willrich, the land owner on the bluff, to bury these men on his property on the heights south of La Grange. Willrich had purchased the land from David Berry, who at 70 years old was killed in The Dawson Massacre, thus returning him to the land that he originally owned.

Final interment was made on September 18, 1848 with full military honors in a tomb constructed by Heinrich Kreische for which he was paid $20.00 for his efforts. The ceremony was attended by over 1000 people.

Photo caption: Original tomb built by Heinrich Kreische that contained the remains of victims of the Dawson and Mier Expeditions; courtesy of Fayette Heritage Museum and Archives.

Sources:

Abolafia-Rosenzweig, Mark. The Dawson and Mier Expeditions and Their Place in Texas History; September 1986

Texas Parks and Wildlife; Docent Manual for Monument Hill and Kreische’s Brewery State Historic Sites, Chapter 7

Transcription from “The Adventures and Recollections of General Walter P. Lane Containing Sketches of the Texan, Mexican, and Late Wars with Several Indian Fights Thrown In”; Pemberton Press, Jenkins Publishing Company; Austin and NewYork, 1970, pp 64-69.

Kreische and the Tomb

By Charles Hebert

Heinrich Kreische, a talented stonemason, who emigrated from Saxony, Germany, arrived in Texas in 1840. After settling in Fayette County, he was hired to build the Dawson and Mier tomb on the bluff overlooking La Grange. In early 1849, he purchased 172 and ¼ acres of land from George Willrich, including the tomb. It was on this site that Kreische built his home with the added responsibility of keeping the tomb in good repair, which he reluctantly accepted. In 1850, Kreische entered into an agreement with the Texas Monument Committee with the goal to erect a suitable monument on the property at a cost of $150,000 to honor the fallen heroes. Correspondence and articles in newspapers at that time reveal that the term “monument” was being used to describe a better vault that would cover the existing tomb.

Heinrich Kreische, a talented stonemason, who emigrated from Saxony, Germany, arrived in Texas in 1840. After settling in Fayette County, he was hired to build the Dawson and Mier tomb on the bluff overlooking La Grange. In early 1849, he purchased 172 and ¼ acres of land from George Willrich, including the tomb. It was on this site that Kreische built his home with the added responsibility of keeping the tomb in good repair, which he reluctantly accepted. In 1850, Kreische entered into an agreement with the Texas Monument Committee with the goal to erect a suitable monument on the property at a cost of $150,000 to honor the fallen heroes. Correspondence and articles in newspapers at that time reveal that the term “monument” was being used to describe a better vault that would cover the existing tomb.

Kreische agreed to deed the Monument Committee 10 acres of land “…under one condition, that the so-called committee will place the cornerstone for this monument within 15 years, then I will also sell to the committee 10 acres of land which will include the burial grounds.” The committee made no contact with Kreische for 21 years. However, the Texas Vorwarts, a German-language newspaper, published information that lots of money had been collected for the upkeep of the burial grounds, but Kreische noted that he had not received one cent for the upkeep of the grounds or the tomb.

Dr. William P. Smith, editor of The Texas Monument newspaper, solicited donations for the cause of erecting a proper monument for the tomb, and a committee of several veterans, some in other states by this time, served as fund raisers for the Texas Monument Committee. The people of La Grange, after some success at raising funds for a monument, met in an important meeting on March 9, 1856. The citizens decided instead that “funds in the hands of the board shall be used for the purpose of erecting suitable buildings for the Monument University to be erected at Rutersville in honor of all who have fallen in the cause of Texas Liberty, whether in battle with the Mexicans, or died in service to their county.” The funds were transferred from their original intended purpose of maintaining the tomb and burial grounds to one of building a living memorial for the future leaders of Texas. The resulting institution, The Military College of Rutersville, capitalizing on the traditions that had grown from Monument Hill and other sites pertaining to Texas’ struggle for freedom, was dedicated for this purpose.

A new committee, named Allemania, evolving from the old Monument Committee, was created. On March 18, 1871, Kriesche addressed his concerns about the Allemania committee through a newspaper letter in which he expressed his frustration, “…take a good look at this Allemania bunch,” he wrote. “I have no confidence in them, even less than for the Monument Committee.” The Allemania of La Grange met on March 25, 1871 after Kreische’s published comments and acknowledged in a subsequent newspaper article that the tomb was in disrepair and in need of attention. This was followed by a second article appearing in the Texas Vorwarts, noting that the money for that purpose was collected but used elsewhere and imploring the citizens to act immediately to rectify the deplorable condition of the tomb. The La Grange Journal noted, “…the bones of the heroes are subject to the sun light and bleached by it.” Expressing his frustration with the Allamania, Kreische further added that “…these young people have no idea of manual labor, and do not want to know it. All they want is glory and they don’t even know the reason these heroes are buried up here.” Kreische in another letter to the Texas Vorwarts, dated April 11, 1871, noted that the formed committee “…will start a new fraud, therefore I would like to warn my fellow citizens of La Grange. We had enough trickery in the past.”

On May 17, 1872, there was a newspaper announcement stating that “The Allemania Brass Band” would be having a dance to benefit “the reparation of the Monument on the Bluff.” The event was held on May 19, but not before the Allemania took issue with Kreische referring to the bluff as “Kreisher’s Bluff”, calling it “Human nonsense” and more or less admonishing him, while at the same time thanking him for his due diligence for maintaining the tomb over the years at no cost to the state. Kreische’s untimely death in March 1882 should have settled the disputes, but not so.

“LET US BE UP AND DOING” read the headline from The Dawson-Eastland Chapter of the Daughters of the Republic of Texas in the October 20, 1904 issue of The La Grange Journal. The focus of the article concentrated on the legal aspects and rights of The General Society of The Daughters of the Republic and their charter under the laws of the state - that the “association may have, hold or purchase, grant, gift or otherwise, real estate on which battles for the independence of Texas were fought, such monuments as may be erected thereon, and burial grounds where the dead who fought and died for Texas Independence are buried. It obviates the necessity of special legislation; it saves time, expense and trouble”.

Mrs. Josepha Kreische addressed the controversy in an open letter to The La Grange Journal on November 4, 1904, reiterating the agreement the Monument Committee had made with her husband and admonishing that after 15 years nothing was done. She noted how “Things have changed greatly over the past thirty years; a road now runs by the vault of the Dawson men and there is a Schutzen Park with a beer garden and dancing within a few feet of the vault. Grave yards and beer gardens in one and the same yard together does not look well.” Vandalism of the tomb was widespread as trespassers took bones from the tomb despite the efforts of Mrs. Kreische who constructed a barbed wire fence around the tomb to no avail as the “vandals go in anyway”. Mrs. Kreische, frustrated by the interference, openly displayed her displeasure with the Daughters of the Republic of Texas and accused them of “…trying to force her to sell a piece of the land in the midst of my homestead, in front of my dwelling, and to remove the monument of the Mier prisoners from the court house park thereon”. She concluded, “No my dear ladies, my home is as dear and sacred to me as is the noble and worthy cause to erect a monument from the fallen heroes, to you. Nobody would part with a piece of ground, having improvements all around his home. It is folly to class the Bluff in line with San Jacinto, the Alamo and Goliad, there is grand difference - yes very”. Josepha Kreische died in January 1906, and with her passing she bequeathed in her will that the property should pass to her oldest son, Henry Louis, to defend their legacy.

Mrs. Josepha Kreische addressed the controversy in an open letter to The La Grange Journal on November 4, 1904, reiterating the agreement the Monument Committee had made with her husband and admonishing that after 15 years nothing was done. She noted how “Things have changed greatly over the past thirty years; a road now runs by the vault of the Dawson men and there is a Schutzen Park with a beer garden and dancing within a few feet of the vault. Grave yards and beer gardens in one and the same yard together does not look well.” Vandalism of the tomb was widespread as trespassers took bones from the tomb despite the efforts of Mrs. Kreische who constructed a barbed wire fence around the tomb to no avail as the “vandals go in anyway”. Mrs. Kreische, frustrated by the interference, openly displayed her displeasure with the Daughters of the Republic of Texas and accused them of “…trying to force her to sell a piece of the land in the midst of my homestead, in front of my dwelling, and to remove the monument of the Mier prisoners from the court house park thereon”. She concluded, “No my dear ladies, my home is as dear and sacred to me as is the noble and worthy cause to erect a monument from the fallen heroes, to you. Nobody would part with a piece of ground, having improvements all around his home. It is folly to class the Bluff in line with San Jacinto, the Alamo and Goliad, there is grand difference - yes very”. Josepha Kreische died in January 1906, and with her passing she bequeathed in her will that the property should pass to her oldest son, Henry Louis, to defend their legacy.

On June 24, 1907, the state acquired the Monument Hill tomb and 0.36 acres. In 1931, The Daughters of the Republic of Texas built a wrought iron fence around the tomb, and in May 1933, Monument Hill became a state park. A new granite vault that was placed over the original tomb was dedicated on September 18th of that same year. A 48-foot shell stone monument with an art deco mural was erected as a memorial in 1936 at the time of The Texas Centennial. Julia Kreische, the youngest child of Heinrich and Josepha Kreische and last surviving heir, died in 1952, leaving the family estate to the Hostyn Catholic Church. Julia was so bitter with the transgressions to her property that she threatened at one time to “throw the bones over the bluff.”

Photo caption:

Top:

Front of Kreische home on the bluff with unknown group, circa 1890s; courtesy of Fayette Heritage Museum and Archives

Bottom: Old deteriorated vault with unknown man and skeletal remains on top; courtesy of Fayette Heritage Museum and Archives.

Sources:

Abolafia-Rosenzweig, Mark. The Dawson and Mier Expeditions and Their Place in Texas History; September 1986

Texas Parks and Wildlife Docent Manual for Monument Hill and Kreische Brewery State Historic Sites, Chapter 7

Texas Vorwarts; March 18, March 25 & April 11, 1871

The La Grange Journal; October 20, & November 3, 1904

Texas, Our Texas

by Sylvia Hebert

During the days of this past weekend, I received a humbling reminder of how fortunate I am to be just where I am on this vast bubble of dirt called Earth. It is no secret that citizens of the great state of Texas are very proud of the “BIG-ness” of their chosen homeland. New residents of the state, especially all former Yankees, are teased that although they were not fortunate enough to be born in Texas, they had the good sense to get here as fast as they could.

During the days of this past weekend, I received a humbling reminder of how fortunate I am to be just where I am on this vast bubble of dirt called Earth. It is no secret that citizens of the great state of Texas are very proud of the “BIG-ness” of their chosen homeland. New residents of the state, especially all former Yankees, are teased that although they were not fortunate enough to be born in Texas, they had the good sense to get here as fast as they could.

Everyone remembers the Battle of the Alamo. But what about the siege of Bexar, the Goliad Massacre, and the Runaway Scrape? The type of spirit displayed in classroom stories told as legends is the “stuff” the early Texians were made of. A litany of skirmishes, negotiations, conventions, executions, and instrumental detonations had occurred on our way to becoming a Republic. Texas history provides a wellspring of valor, tragedy, and victory within its full-bodied narrative. Perhaps I am more aware of the special quality that leads to heroism due to the extensive research I have been conducting on one of Fayette County’s first and most selfless settlers, a family named Breeding. Crossing a piece of poster board are the names of generations of men and women who began their odyssey in Virginia and trickled as if led by a magnet to the wild open acres, guided by well-used Indian trails. Embedded in Texas history and that of Fayette County are Breeding family members; a Breeding was

- A member of the first board of land commissioners of Fayette County.

- A juror at the first district court session held in Fayette County.

- Elected to serve as the first Fayette County Sheriff

- Charged to house county prisoners in the first county jail, but it was not large enough so he boarded the prisoners out to local residents

- Responsible for beginning the first school in the county

- In the Siege of Bexar, December 1835

- A member of the Texas Rangers

- Enlisted in the Texas army

- On the battlefield at San Jacinto, April 21, 1836

- In the Brazos River ferry skirmish at San Felipe, preventing Santa Anna from crossing the river

- Sent with his wagon team to haul two cannons, the “twin sisters,” to Sam Houston’s army

What examples of Texan heroism! Now comes the inevitable question: How is this depth of duty and patriotism to be passed along to future generations?

After viewing the events of Texas Heroes Day, I believe the keepers of the fire and the faith are alive and well among us. We, the citizens of La Grange and Fayette County, are unbelievably honored to be the home of the Kreiche Brewery / Monument Hill State Historic Sites. The park staff must rank among the best in Texas, and the support always available from the Fayette Public Library Museum and Archives is timely and flawless. For this weekend’s event, a planning committee comprised of members of the Friends of Monument Hill & Kreische Brewery went far beyond what could have been asked of them in order to insure a successful, action-packed yet reverent observation of the fates of the men who gave their lives at the Dawson Massacre, the Drawing of the Black Beans, and the Mier Expedition. The weekend began with an informative and entertaining explanation of the observance given by Greg Walker and Charles Hebert in the library’s meeting room. School participants were also necessary to make the effort whole: 60 essays were displayed in the park’s visitor center, and high school students presented a play Saturday evening in the Texas Heroes Museum. To be especially commended as modern-day heroes are Katy and Greg Beauford, Clara and Julius Bartek, Greg Walker, Tim Scubert, and Bobbie Nash. A host of volunteers are always needed, and they came through in a big way. Marcia Hendrix, the newly-named site manager, has a terrific cast to assist her when the park is reopened after extensive repairs are made.

Texas, our Texas – God bless you Texas! And keep you brave and strong,

That you may grow in power and worth, throughout the ages long.

Photo credit:

Reenactors taken by Carolyn Meiners in 1998 at the 150th Remembrance of the Dawson and Mier Men, courtesy of Fayette Heritage Museum and Archives

Historical Markers

|

Monument Hill Tomb In September 1848, the remains of Texans killed in the 1842 Dawson Massacre and the 1843 "Black Bean Death Lottery" were reburied at this site in a sandstone vault. The Kreische family did its best to care for the grave during their ownership of the property, but it suffered from lack of formal oversight. In 1905, the state authorized acquisition of .36 acres here, and the Daughters of the Republic of Texas raised funds for a new cover for the tomb in 1933. During the 1936 Texas Centennial celebration, the 48-foot shellstone shaft with a stylized, Art Deco-influenced mural was erected to mark the mass grave more prominently. Local citizens purchased 3.54 acres as a donation to the state for parkland in 1957. (2002) |

|

Kreische Complex

German immigrant Heinrich Kreische (1821-1882) purchased nearly 175 acres of property in Fayette County in 1849. A stonemason by trade, he built a house, barn and smokehouse here on the high south bluff above the Colorado River. In the 1860s, Kreische began brewing Bluff Beer near his homesite. Situated on the spring-fed creek, the brewery included an elaborate tunnel system to provide temperature control for the brewing process. Bluff Beer was sold throughout Central Texas and was produced until 1884, two years after Kreische died in a work-related accident. The Kreische complex stands as a reminder of German heritage and culture in this region of the state. (2002)

|

List of Burials

The following data was taken from the booklet Monument Hill State Historic Site: The Dawson and Mier Expeditions and their Place in Texas History by Mark Abolafia-Rosenzweig:

|

NAME

|

DEATH

|

COMMENTS

|

|

Adams, ?

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Alexander, Jerome B.

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Alley, James

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Barkley, Robert

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Beard, John

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Berry, David

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Brookfield, Francis E.

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Butler, Thomas J.

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Cash, John L.

|

25 Mar 1843

|

Executed at Salado, Mexico on the Mier Expedition

|

|

Church, T. John

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Cocke, James D.

|

25 Mar 1843

|

Executed at Salado, Mexico on the Mier Expedition

|

|

Cummings, John

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Dancer, John

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Dawson, Nicholas Mosby

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Dickerson, Lewis W.

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Dunham, Robert Holmes

|

25 Mar 1843

|

Executed at Salado, Mexico on the Mier Expedition

|

|

Eastland, Robert

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Eastland, William Mosby

|

25 Mar 1843

|

Executed at Salado, Mexico on the Mier Expedition

|

|

Este, Edward E.

|

25 Mar 1843

|

Executed at Salado, Mexico on the Mier Expedition

|

|

Farris, Lowe (?)

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Field, Charles S.

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Garey, Elijah

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Griffin, Joe

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Hall, Harvey W.

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Harris, Robert

|

25 Mar 1843

|

Executed at Salado, Mexico on the Mier Expedition

|

|

Hill, George A.

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Jones, Asa

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Jones, John F.

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Jones, Thomas L.

|

25 Mar 1843

|

Executed at Salado, Mexico on the Mier Expedition

|

|

Lewis, Patrick

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Linn, William

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Lowe, Winfield S.

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Maher, Patrick

|

25 Mar 1843

|

Executed at Salado, Mexico on the Mier Expedition

|

|

McGee, Richard

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Ogden, James Masterson

|

25 Mar 1843

|

Executed at Salado, Mexico on the Mier Expedition

|

|

Pendleton, John Wesley

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Rice, Thomas

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Roberts, Christopher

|

25 Mar 1843

|

Executed at Salado, Mexico on the Mier Expedition

|

|

Rowan, William

|

25 Mar 1843

|

Executed at Salado, Mexico on the Mier Expedition

|

|

Savage, William

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Scallorn, John Wesley

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Scallorn, Elam

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Simms, Thomas

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Slack, Richard

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Thompson, Joseph N. M.

|

25 Mar 1843

|

Executed at Salado, Mexico on the Mier Expedition

|

|

Torrey, James N.

|

25 Mar 1843

|

Executed at Salado, Mexico on the Mier Expedition

|

|

Trimble, Edward

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Turnbull, James

|

25 Mar 1843

|

Executed at Salado, Mexico on the Mier Expedition

|

|

Wells, Norman Miles

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

|

Whalen, Henry

|

25 Mar 1843

|

Executed at Salado, Mexico on the Mier Expedition

|

|

Wing, Martin Carroll

|

25 Mar 1843

|

Executed at Salado, Mexico on the Mier Expedition

|

|

Woods, Zadock

|

18 Sep 1842

|

Died at Salado Creek on Dawson Expedition

|

Related Links

Monument Hill State Historic Site and Kreische Brewery State Historic Site

Located on the bluff overlooking La Grange, this picturesque 40.4-acre state park is the site of a tomb containing the remains of members of the Dawson and Mier Expeditions, as well as the ruins of one of the first commercial breweries in Texas.

Monument Hill & Kreische Brewery State Historical Parks

TexasEscapes.com

View of Colorado River from Monument Hill by Gary E. McKee

|

Monument Hill – Kreische Brewery State Historic Site

Dawson Massacre

Mier Expedition

Perote Prison

Black Bean Episode

Jerome B. Alexander

James Decatur Cocke

Nicholas Mosby Dawson

William Mosby Eastland

Patrick Mahan

James M. Ogden

James Nash Torrey

Henry A. Whalen

Martin Carroll Wing

Zadock Woods

All at the Hand book of Texas Online

Participants in the Dawson Massacre

contributed by Dale Martin

The Mier Expedition

Sons of DeWitt Colony Texas Web Site

Eyewitness Descriptions of the Battle of Salado & the Dawson Massacre

Sons of DeWitt Colony Texas Web Site

Journal of the Texian Expedition Against Mier

By Gen. T. J. Green, 1845

Southern Methodist University Web Site

Letters of the "Dawson Men" from Perote Prison, Mexico, 1842-1843

April 1935 article in the Quarterly of the Texas State Historical Association from the Texas State Historical Association website

See Henry L. Kreische Brewery and House Listing in the National Register

On a high bluff overlooking the Colorado River bottom in La Grange, Texas stands a tall limestone shaft. At the base of the shaft is a gray granite crypt containing the remains of heroes of the Republic of Texas. The following is the story of how this beautiful oak covered promontory came to be a shrine to freedom.

On a high bluff overlooking the Colorado River bottom in La Grange, Texas stands a tall limestone shaft. At the base of the shaft is a gray granite crypt containing the remains of heroes of the Republic of Texas. The following is the story of how this beautiful oak covered promontory came to be a shrine to freedom. This announcement spurred the creation of the Monument Hill Memorial Association. When the state returned to begin the move it found that “the ground around the vault cleared off clean as a whistle...the cracked walls repaired and an iron fence with a concrete curb erected around it.” Within two months a fitting granite cover was built over the old sandstone tomb. The 1936 Centennial was a boon for Texas history as the state spent large amounts of money to honor and preserve its heritage. Ten thousand dollars was appropriated for a monument to be placed next to the tomb. The forty foot shaft with the bronze angel at the base was soon completed on the small plot.

This announcement spurred the creation of the Monument Hill Memorial Association. When the state returned to begin the move it found that “the ground around the vault cleared off clean as a whistle...the cracked walls repaired and an iron fence with a concrete curb erected around it.” Within two months a fitting granite cover was built over the old sandstone tomb. The 1936 Centennial was a boon for Texas history as the state spent large amounts of money to honor and preserve its heritage. Ten thousand dollars was appropriated for a monument to be placed next to the tomb. The forty foot shaft with the bronze angel at the base was soon completed on the small plot.

In fact, a typhus epidemic swept through the Perote prison that fall. The disease is a bacterial infection spread by bites from body lice and rat fleas. Scratching the bites opens the skin, allowing greater access of the bacteria into the bloodstream. Initially, there are flu-like symptoms, including a severe headache, high fever, chills, dry cough, muscle and joint pain, followed by a rash, delirium and a coma.

In fact, a typhus epidemic swept through the Perote prison that fall. The disease is a bacterial infection spread by bites from body lice and rat fleas. Scratching the bites opens the skin, allowing greater access of the bacteria into the bloodstream. Initially, there are flu-like symptoms, including a severe headache, high fever, chills, dry cough, muscle and joint pain, followed by a rash, delirium and a coma.  However, the remains of the Dawson men still had to be retrieved. A county-wide meeting was held on the square in La Grange, and men from throughout the county were delegated to exhume the remains from the massacre at Salado Creek outside of San Antonio and return them to Fayette County for reburial. Once accomplished, the remains were placed in two coffins; one for the Dawson men and the other for the victims of the Black Bean Incident. Arrangements were made with George Willrich, the land owner on the bluff, to bury these men on his property on the heights south of La Grange. Willrich had purchased the land from David Berry, who at 70 years old was killed in The Dawson Massacre, thus returning him to the land that he originally owned.

However, the remains of the Dawson men still had to be retrieved. A county-wide meeting was held on the square in La Grange, and men from throughout the county were delegated to exhume the remains from the massacre at Salado Creek outside of San Antonio and return them to Fayette County for reburial. Once accomplished, the remains were placed in two coffins; one for the Dawson men and the other for the victims of the Black Bean Incident. Arrangements were made with George Willrich, the land owner on the bluff, to bury these men on his property on the heights south of La Grange. Willrich had purchased the land from David Berry, who at 70 years old was killed in The Dawson Massacre, thus returning him to the land that he originally owned.  Heinrich Kreische, a talented stonemason, who emigrated from Saxony, Germany, arrived in Texas in 1840. After settling in Fayette County, he was hired to build the Dawson and Mier tomb on the bluff overlooking La Grange. In early 1849, he purchased 172 and ¼ acres of land from George Willrich, including the tomb. It was on this site that Kreische built his home with the added responsibility of keeping the tomb in good repair, which he reluctantly accepted. In 1850, Kreische entered into an agreement with the Texas Monument Committee with the goal to erect a suitable monument on the property at a cost of $150,000 to honor the fallen heroes. Correspondence and articles in newspapers at that time reveal that the term “monument” was being used to describe a better vault that would cover the existing tomb.

Heinrich Kreische, a talented stonemason, who emigrated from Saxony, Germany, arrived in Texas in 1840. After settling in Fayette County, he was hired to build the Dawson and Mier tomb on the bluff overlooking La Grange. In early 1849, he purchased 172 and ¼ acres of land from George Willrich, including the tomb. It was on this site that Kreische built his home with the added responsibility of keeping the tomb in good repair, which he reluctantly accepted. In 1850, Kreische entered into an agreement with the Texas Monument Committee with the goal to erect a suitable monument on the property at a cost of $150,000 to honor the fallen heroes. Correspondence and articles in newspapers at that time reveal that the term “monument” was being used to describe a better vault that would cover the existing tomb. Mrs. Josepha Kreische addressed the controversy in an open letter to The La Grange Journal on November 4, 1904, reiterating the agreement the Monument Committee had made with her husband and admonishing that after 15 years nothing was done. She noted how “Things have changed greatly over the past thirty years; a road now runs by the vault of the Dawson men and there is a Schutzen Park with a beer garden and dancing within a few feet of the vault. Grave yards and beer gardens in one and the same yard together does not look well.” Vandalism of the tomb was widespread as trespassers took bones from the tomb despite the efforts of Mrs. Kreische who constructed a barbed wire fence around the tomb to no avail as the “vandals go in anyway”. Mrs. Kreische, frustrated by the interference, openly displayed her displeasure with the Daughters of the Republic of Texas and accused them of “…trying to force her to sell a piece of the land in the midst of my homestead, in front of my dwelling, and to remove the monument of the Mier prisoners from the court house park thereon”. She concluded, “No my dear ladies, my home is as dear and sacred to me as is the noble and worthy cause to erect a monument from the fallen heroes, to you. Nobody would part with a piece of ground, having improvements all around his home. It is folly to class the Bluff in line with San Jacinto, the Alamo and Goliad, there is grand difference - yes very”. Josepha Kreische died in January 1906, and with her passing she bequeathed in her will that the property should pass to her oldest son, Henry Louis, to defend their legacy.

Mrs. Josepha Kreische addressed the controversy in an open letter to The La Grange Journal on November 4, 1904, reiterating the agreement the Monument Committee had made with her husband and admonishing that after 15 years nothing was done. She noted how “Things have changed greatly over the past thirty years; a road now runs by the vault of the Dawson men and there is a Schutzen Park with a beer garden and dancing within a few feet of the vault. Grave yards and beer gardens in one and the same yard together does not look well.” Vandalism of the tomb was widespread as trespassers took bones from the tomb despite the efforts of Mrs. Kreische who constructed a barbed wire fence around the tomb to no avail as the “vandals go in anyway”. Mrs. Kreische, frustrated by the interference, openly displayed her displeasure with the Daughters of the Republic of Texas and accused them of “…trying to force her to sell a piece of the land in the midst of my homestead, in front of my dwelling, and to remove the monument of the Mier prisoners from the court house park thereon”. She concluded, “No my dear ladies, my home is as dear and sacred to me as is the noble and worthy cause to erect a monument from the fallen heroes, to you. Nobody would part with a piece of ground, having improvements all around his home. It is folly to class the Bluff in line with San Jacinto, the Alamo and Goliad, there is grand difference - yes very”. Josepha Kreische died in January 1906, and with her passing she bequeathed in her will that the property should pass to her oldest son, Henry Louis, to defend their legacy.  During the days of this past weekend, I received a humbling reminder of how fortunate I am to be just where I am on this vast bubble of dirt called Earth. It is no secret that citizens of the great state of Texas are very proud of the “BIG-ness” of their chosen homeland. New residents of the state, especially all former Yankees, are teased that although they were not fortunate enough to be born in Texas, they had the good sense to get here as fast as they could.

During the days of this past weekend, I received a humbling reminder of how fortunate I am to be just where I am on this vast bubble of dirt called Earth. It is no secret that citizens of the great state of Texas are very proud of the “BIG-ness” of their chosen homeland. New residents of the state, especially all former Yankees, are teased that although they were not fortunate enough to be born in Texas, they had the good sense to get here as fast as they could.